Patriarchy Is Monkey Business—Just Ask the Bonobo Species

Diane Rosenfeld has long been a legal expert on gender-based violence, and one of her biggest sources of hope isn't even from humans.

Unlike many primates, bonobos—a species of apes that are native to the Congo Basin region in Central Africa—are a matriarchal bunch who protect each other when male bonobos target them. This is a vast difference from the leaps and bounds far too many women in the United States have to take when leaving abusive relationships.

Diane Rosenfeld, director of the Gender Violence Program at Harvard Law School, believes that we can learn from how female bonobos protect each other, and she also is confident that a bonobo sisterhood among humans can be beneficial to people of all genders.

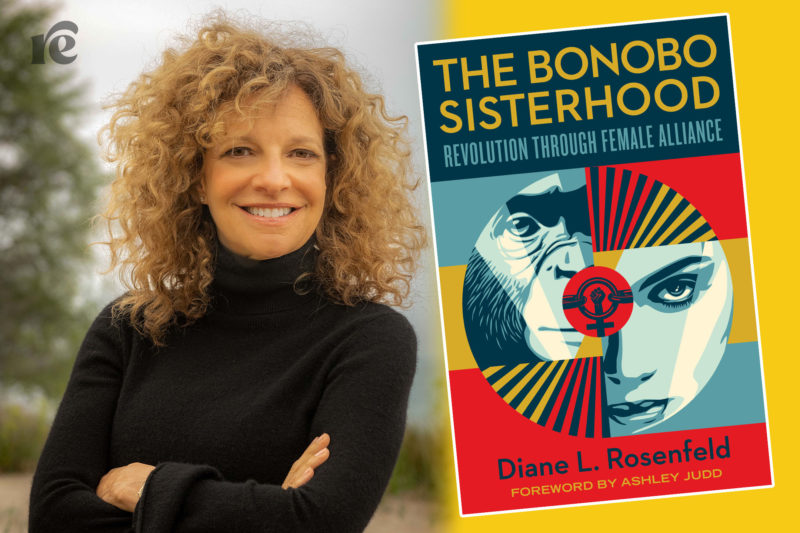

“In a patriarchal system, men also suffer terribly, and I want this book to be an invitation to people of all genders to just re-examine the system,” Rosenfeld told Rewire News Group. Rosenfeld’s book, aptly named The Bonobo Sisterhood: Revolution Through Female Alliance, is being released today by Harper Wave.

Rewire News Group chatted with Rosenfeld about how some current and past legal practices uphold patriarchal violence, the inspiration we can take from bonobos, and why we can look forward to a better future with female alliances.

This interview has been lightly edited for length.

Rewire News Group: Despite most governments forming under patriarchal systems, what gives you the aspiration that we can move to a society away from gender-based violence?

Diane Rosenfeld: How can you have a patriarchal democracy when it’s really an oxymoron? When you think about it, a patriarchal system at its basis excludes women by definition. We have to have other answers and the bonobos offer us this inspiration, this hope, this social order, that is not patriarchal, that is totally possible, and it is scientifically proven through their existence.

RNG: In reading your book, I found it interesting how you highlighted that women’s safety shelters still protect men holding onto their homes. Could you share more about that?

DR: It was working on a case years ago that woke me up to the fundamental injustice of our system. I was helping a domestic violence victim to court get her order of protection, and her abuser was able to get a 30-day continuance for the hearing, and the judge didn’t even take the time to hear that the emergency order of protection had already been violated extremely dangerously by this man. I was the acting chief of the women’s advocacy division of the Illinois Attorney General’s Office, and I, the court advocate, went with the victim to make her a safety plan. We all decided she needed to go to a shelter to hide, and, at that moment, the injustice of the situation struck me like the proverbial brick on my head, and I said, “What’s wrong with this picture?” I am now complicit in this system where I’m helping to send her into hiding.

Laws were made between men among men, identifying men’s interests, and enshrining their domination over women. This is exceptionally important in the patriarchal home, where man was designated as king of his castle. In [William] Blackstone’s legal commentaries from the 18th century, he talks about the difference legally between a man killing his wife and a wife killing her husband, and this is very important to the whole question. If a man killed his wife, legally, it was exactly the same as if he had killed a stranger. If a woman killed her husband, it was an act of treason, for which she would be put to death.

RNG: How does poverty play a role in helping male perpetrators continue to have control over women, both in their homes and in the courts?

DR: The feminization of poverty is something that’s been studied, and it’s also something that shouldn’t surprise us in an economic system, as it’s also the product of patriarchy. We’ve never achieved anywhere near equality in this economic system in the United States, and women who are poor have far less choices than women who have access to wealth and privilege.

What I think is going to be a really interesting experiment that I presented in this book is to think about equality among and between women. When we do that, and when women start to recognize that we have resources that we should value among ourselves, and share among ourselves like the bonobos do, we can come up with our own—not just equality, but a much richer sense of abundance of what we need and what we can share.

So bonobos share their food, and bonobo infants outrank adult males, such that an infant who takes food from the mouth of an adult male will have no consequences. They will not ever harm the infant. This is significant because in the bonobos, there has been no infanticide and no killing ever witnessed among them. It shows us that it’s possible to have a peaceful cooperative society, and food sharing is just one example of how the bonobos get along and ensure their food.

RNG: When writing and researching The Bonobo Sisterhood, were there any biases of your own that you re-examined?

DR: One bias and one lesson that I’d love to share with you. The bias came from representing sexual assault victims in their title nine cases, which has been a big focus of my work over the last two decades. What I learned from that is that an assault is an experience and that as someone who has not been sexually assaulted, I can’t place judgment on how that assault was experienced with that particular victim because everyone experiences it differently. So, something that might seem minor or less traumatic to me is just a projection of my own judgment, and it’s wrong.

This is related to the second point and related to the idea of the bonobo call. I heard an attorney- professor-activist-domestic violence survivor, Sarah Buel, speak two decades ago and she said, if you haven’t been assaulted, if you haven’t been a victim of domestic violence, you have more of a duty to help. I really heard that as a bonobo call, even though at the time I didn’t know what those were. I think that it really is a call among all women to help each other no matter what and to just stand up for each other.

What I mean by the bonobo call is the bonobos have eliminated male sexual coercion through their strong female alliances. The way it works is that if a female bonobo was aggressed upon by male, she emits a special cry, and all the other females within earshot, whether they know her, like her, or are related to her, immediately come to her aid, and they formed this instantaneous coalition. They fend off the male and sometimes sent him into isolation.

RNG: What gives you hope about feminist alliances moving forward?

DR: Bonobos give me hope because they are living proof that patriarchy is not inevitable. Ashley Judd gives me hope. She was in my class as my student when she was at the Kennedy School, and metabolized everything that I taught in the class, then went on to be so brave and courageous and come out publicly as the first person against Harvey Weinstein.

My hope is that this book offers us that systemic response. It offers us a roadmap to believe that we each have a self-worth defending, and that our sister has a self-worth defending. A helpful principle to keep in mind is what I call the bonobo principle. It seems to me the bonobos act on this principle, that if it can happen to her, it can happen to me. The bonobo principle in my interpretation is a two-part principle: first part, no one has the right to exploit, abuse, threaten, harass, and/or gaslight my sister; the second part of the principle is the belief that everybody’s my sister.