Testing Sexual Assault Kits Is Not Always a Path to Justice

The DOJ's Sexual Assault Kit Initiative has led to significant changes, but there's still no recourse for many victims.

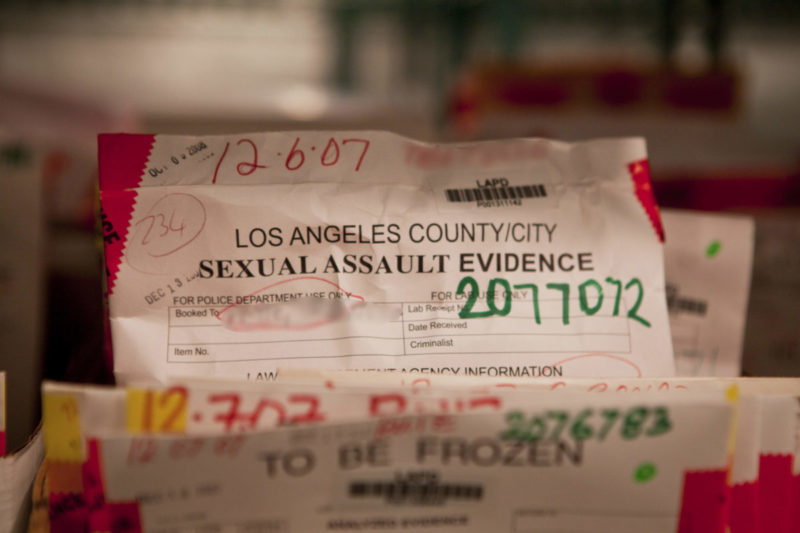

In the early 2010s, a wave of news stories described an unthinkable horror to many—hundreds of thousands of untested sexual assault kits sitting on shelves while the alleged perpetrators of those assaults walked free. Sexual assault kits had either been destroyed by police departments, ruined by inappropriate storage, or were just languishing on shelves in police evidence rooms.

It was enraging. The hubris of police and prosecutors ignoring the pain of hundreds of thousands of people who had taken the difficult step of having a sexual assault kit collected was hard to digest.

As a result of that reporting and the pressure that followed, the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance created the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI) in 2015 to clear as many of those kits as quickly as possible.

The idea was that once the hundreds of thousands of old sexual assault kits are cleared, there should never be a backlog again. SAKI also provides law enforcement officers dealing with victims of sexual assault with trauma-informed training to help them work with victims. And the initiative helps law enforcement update investigative methods for dealing with sexual assault crimes and kits.

Clearing sexual assault kits

Corbin Thorley, the cold case victim advocate for Rape Crisis of Cumberland County in North Carolina, said she has a close relationship with the SAKI-funded cold case investigators at her local police department. While she is employed by the rape crisis center, her job is funded by a SAKI grant, and she attends SAKI webinars on becoming trauma-informed alongside the investigators.

Thorley meets regularly with the investigators to review the progress of cold cases. They allow her to review the original investigation files, where she has seen evidence of how the original investigators had little understanding of how trauma manifests. For example, Thorley said, a file might mention that the victim smiled or laughed during an interview, so the investigator did not believe she could have been raped.

“Reading the difference between the notes from the 1993 files compared to what I see during current interviews is a world of difference,” Thorley said.

In her role, Thorley is responsible for notifying victims of cold cases as to the status of their sexual assault kit once it has been tested. When she gives them updates, it’s “like a box of chocolates doesn’t begin to explain the different reactions,” she said. Some express a lot of frustration while others are relieved that their cases have not been forgotten.

Thorley accompanies victims when they are brought in to have their cases re-looked at with investigators. She said victims often express surprise at the difference in the investigators’ attitudes and described it as a “pretty powerful and positive experience.”

Cumberland County has cleared their sexual assault kit backlog of over 700 kits and is now in the process of following up on the information, according to Thorley.

Making arrests

SAKI provides funding for jurisdictions like Cumberland County to clear the vast number of untested sexual assault kits. Without the initiative’s funding and technical training, these kits would still be on the shelves. And while much work remains to clear the national backlog of kits, initial data from SAKI shows some progress.

From SAKI’s inception in 2015 through March 2021, over 125,000 kits have been inventoried with 68,842 tested to completion. From those completed kits, there were 12,127 hits in CODIS, the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, according to the initiative’s website. Over 16,000 investigations were completed with 1,652 cases charged, leading to 924 convictions (including plea agreements). Many of the convicted perpetrators committed other violent crimes, including homicide. Some are serial rapists.

For example, in October 2020, the police department in Durham, North Carolina, held a press conference to announce that its Cold Case Sexual Assault Unit, which is funded by a SAKI grant, had filed charges against 11 people in 15 sexual assault cases dating back to 1984.

In May, a man pled guilty to the rape and murder of three Dallas women. The Dallas County District Attorney’s office credited the funding of additional cold case detectives and prosecutors through a SAKI grant as key to solving the case and extraditing the suspect from Mexico to stand trial.

Also that month, a 45-year-old man was convicted in Akron, Ohio, in four rape cases going back to 2011. In each case, DNA was collected but not tested until SAKI got involved.

Looking toward the future

The SAKI Training and Technical Assistance (TTA) program is making significant changes in the places that have received grants. Backlogs of sexual assault kits are being cleared and police departments are gaining new investigative tools. The focus on protocols for interacting with sexual assault victims is a breath of fresh air. However, the program only addresses 57 percent of the country. Victims in the other 43 percent of the country are still waiting.

Victims also continue to face a litany of issues in trying to get their cases prosecuted. While SAKI is making headway in addressing sexual assaults, the progress is uneven. Jurisdictions that received the first round of grants are ahead of those who received them later. And with almost half the country not receiving any of the training or technical assistance, many victims still deal with investigators who do not believe them or prosecutors unwilling to take difficult cases to court.

And in many places, the sexual assault kits are still backlogged. While SAKI is a net positive for improving criminal justice responses to sexual assault, the lack of coverage for all areas of the country leaves many victims out in the cold with no recourse for justice.

In the meantime, some serial rapists and murderers are continuing with their crimes. In my home state of North Carolina, SAKI wasn’t enough to save the life of 13-year-old Hania Aguilar. The man accused of raping and murdering Aguilar in 2018 had been linked to a 2016 rape through DNA found in the sexual assault kit; the kit was tested in 2017, but the sheriff’s office never followed up on the results. This is the kind of procedural failure that the SAKI TTA program aims to prevent.

This project illuminates the grave injustices that sexual assault survivors have had to endure. From investigators who doubt them to ones who do not understand how to interview them, victims have had a long road to justice if they ever received it. The SAKI TTA program aims to move us toward a criminal justice system that takes the needs of victims seriously.

When victims can be assured that reporting a sexual assault does not open them up to their lives being put on display and that the crime will be fully investigated, more sexual assaults will be reported and prosecuted.