This Texas City Has a Terrible New Way to Harass Abortion Providers

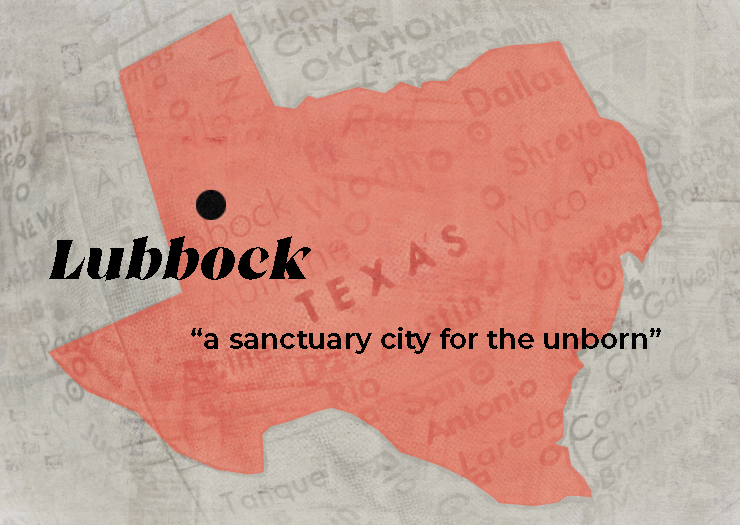

Lubbock, Texas, is the largest city to try to ban abortion within city limits—along with anyone helping the patient and providers.

Have you driven a friend to their abortion appointment? Have you talked someone through a medication abortion on the phone? What about an abortion fund—do you work for one? Ever donated to one? Well congratulations, you aided and abetted a criminal abortion.

Welcome to Lubbock, Texas, a “sanctuary city for the unborn.”

Here, you’ll find a city that just made abortion illegal, and has turned anyone who helps another person get an abortion into a criminal.

Earlier this month, Lubbock residents voted in favor of an ordinance that outlaws abortion within city limits, making it the largest U.S. city to try to ban abortion. Now, we’ve seen abortion bans pass state legislatures before—but the Lubbock ordinance is different.

BREAKING: Lubbock has voted to become the largest city in the country to outlaw abortion in city limits. https://t.co/cykvar1h6Q

— KLBK News (@KLBKNews) May 2, 2021

The ordinance wants to make it a crime to have an abortion, perform an abortion, or even help anyone do those things. And it gives standing to anyone in Texas to sue under the law, which means a lawsuit can be brought against a provider by any anti-abortion zealot in the state.

These two provisions could have grave implications for the city; a Planned Parenthood clinic opened in Lubbock last year, and just began offering abortion care last month (advocates think the ordinance is a retaliatory move); and Texas is home to numerous abortion funds and mutual aid funds that help people access abortion in a state riddled with restrictions.

Here’s a closer look at what the standing and aiding/abetting provisions in the law will actually mean for Lubbock residents.

Who can enforce this law?

“Standing” is legalese for saying “who has the interests to sue under this law,” and typically, when it comes to abortion restrictions, that’s people who the laws affect—namely, patients and providers. Makes sense, right? They’re the ones affected by the law, so they’re the ones who have standing to seek redress (legalese for: relief, remedy) under it, and it’s been that way for decades.

But in this case, the ordinance allows for “third-party standing,” which confers standing to anyone—and we mean anyone—who wants to sue under the law.

Basically they’re deputizing anyone in Texas as an abortion restriction enforcer.

This means that patients and providers are vulnerable to lawsuits from literally any anti-abortion zealot in Texas; and even if they don’t actually win in court, lawsuits like these will make life a living hell for the people this ordinance implicates—tying them up in costly and time-consuming court battles that they wouldn’t have otherwise been subject to. It also has the potential to create a chilling effect: forcing those implicated by the law, like abortion funds or providers, to stop offering services in Lubbuck to avoid being the target of a lawsuit.

The standing provision almost directly mirrors the one included in SB 8, a bill close to passage in the Texas state legislature. SB 8 includes a similar provision granting third-party standing to anyone who wants to attack abortion access in the state.

This attempt to expand third-party standing comes at the same time anti-choice advocates are vigorously challenging the ability of abortion providers to challenge abortion restrictions on behalf of their patients.

Who does the law criminalize?

The ordinance criminalizes anyone who helps another person get an abortion, including anyone who provides transportation to an abortion, anyone who offers instructions for self-managed abortion, or anyone who helps someone pay for their abortion. If you do any of these things, you can be charged with aiding and abetting, which is legal-speak for helping. This is, as Rewire News Group Senior Editor, Law and Policy, Imani Gandy put it, “five alarm bad.”

this is five alarm bad.

this means any person who donates to an abortion fund is "aiding and abetting" an abortion.

christ. https://t.co/nYXYIkrnh9

— Imani Gandy (Orca’s Version) ⚓️ (@AngryBlackLady) May 4, 2021

Out of the gate, anti-abortion lawmakers and voters acting like they care about reproductive coercion is laughable. Reproductive coercion is a type of sexual abuse that involves forcing your partner to abide by a certain family planning or reproductive health decision, like birth control sabotage or removing a condom during sex. If anti-abortion lawmakers cared about survivors of this kind of abuse, they would ensure people could access a full range of reproductive health care as easily as possible. Not to mention that abortion restrictions and bans are coercive in that they literally control people’s family planning decisions.

Self-managed abortion is largely understood to be the next frontier in the fight to ban abortion; after a year-plus of increased demand for telemedicine and directives from federal health agencies affirming the safety of medication abortion, it’s clear that self-managed will be the way of the abortion future for many who want to end a pregnancy in the first trimester. That is undoubtedly a good thing, but it means anti-abortion lawmakers are going to set their sights on restricting it, like they are here.

The criminalization of anyone who helps pay for an abortion is perhaps the furthest-reaching section of the ordinance, in that it could apply to everyone from the friend who literally puts cash in your hand to pay for your abortion, to the Lubbuck resident with a monthly donation set up to their local abortion fund, and even the abortion fund volunteers and workers. This section also drives home what is a constant in abortion restrictions: that these burdens always fall the hardest on the most marginalized.

Like the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal money from funding abortion—any restriction on how someone pays for an abortion perpetuates longstanding systemic discrimination that most adversely impacts poor people, people of color, disabled people, and other marginalized communities trying to access abortion.

Finally, let’s talk about the criminalization of anyone who transports someone to an abortion. This one might seem a bit out of left field, but lawmakers are simply taking a page from the playbook of laws that restrict abortion access for young people.

You see, abortion laws for young people vary from state to state, which means that sometimes young people opt to travel to a state where parental consent or judicial consent aren’t necessary rather than go through that arduous process at home. So one way lawmakers have tried to curb access for minors is by trying to criminalize transporting a minor to another state for an abortion.

This also isn’t the first time conservative lawmakers have looked to access for minors as a blueprint for further abortion restrictions; earlier this year, Tennessee lawmakers tried to pass a spousal consent law, giving cis men veto power over pregnant people’s abortions—the same way young people need parental consent. Abortion access for young people is an often overlooked topic, and lawmakers count on that indifference. If no one is outraged about consent or travel restrictions for young people, it becomes easy fodder for new restrictions on adults seeking abortion care as well.

None of these are entirely new ideas in the anti-abortion space: empowering people other than the pregnant person with the control over abortion, fearmongering about criminalization. They are manifestations of other barriers that fall the hardest on marginalized people—on cost, on a full range of abortion care options, on barriers for people living with abuse, and on age.

The Lubbock ordinance is a mess of confusing provisions, and it’s obvious that it was written not by lawmakers with an understanding of the law, but by activists with the sole intent to restrict abortion access by any means necessary. It’s unclear what happens next with this ordinance, but abortion restrictions like these do not happen in a vaccum.

As Yamani Hernandez, executive director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, said in a statement, “What happens in Texas does not stay in Texas.”