What the Mothers of 3 Civil Rights Leaders Can Teach Us Today

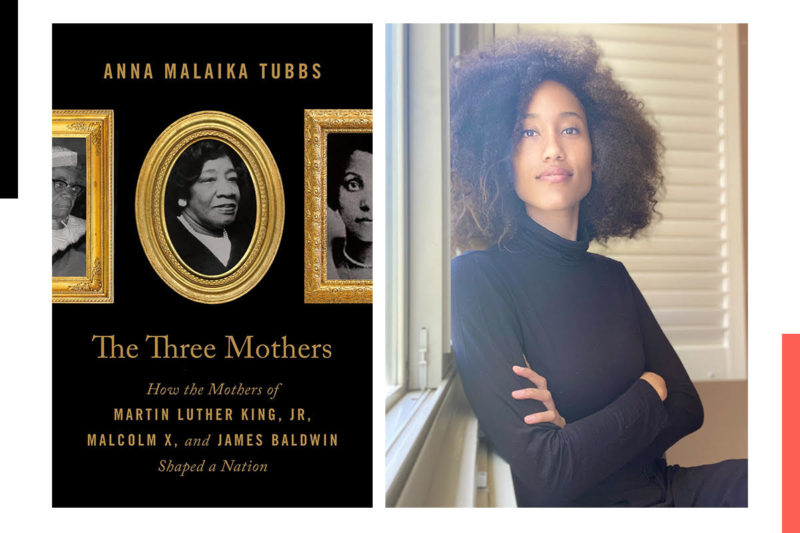

Anna Malaika Tubbs' debut book, The Three Mothers, highlights how Berdis Baldwin, Louise Little, and Alberta King shaped a nation.

Berdis Baldwin, Louise Little, and Alberta King—you may not recognize their names, but you know the sons they raised: James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

With her debut book, Anna Malaika Tubbs wanted to write something connected to the erasure of Black women in history, and she found her story in the Black women who shaped these civil rights figures.

“They all come from really different backgrounds—one from a small town, one’s from an island, and one’s from the South,” Tubbs told Rewire News Group. “They all had different educations and support systems and access to resources and different tragedies they experienced, so it helps to tell this cool story of history in the United States through the perspectives of three very different Black women.”

“They were all born within ten years of each other, and their famous sons were all born within five years of each other, and it was almost uncanny how closely aligned their stories were even though they diverged in so many ways,” she continued.

The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, which is being released today, was personal for Tubbs, who became pregnant with her son while writing it. She said she found it breathtaking to think about what these women, who had their children in the 1920s, went through living in a country hostile to their existence.

Details about these women’s lives scarce have been scarce, so Tubbs researched their lives, finding out about Berdis Baldwin growing up on an isolated island off Maryland after her mother died in childbirth. In Grenada, Louise Little’s birthplace, people were proud of their history of resistance to white oppression; she later went to Montreal to work with Marcus Garvey’s movement. And Alberta King grew up in a family with deep ties to Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where she led the choir, and where her father, husband, and son preached (and where Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock is senior pastor).

Rewire News Group spoke with Tubbs, who got her master’s degree in multidisciplinary gender studies at Cambridge University, where she’s now a PhD candidate in sociology, about the dehumanization of Black women, how these mothers influenced who their sons became, and how she responds when people congratulate her husband on the birth of their son. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Rewire News Group: You’ve talked about the erasure of Black women—how specifically do you see Black motherhood being erased?

Anna Malaika Tubbs: I think there is a current maternal health crisis that we’re not paying attention to. Despite economic access to resources and socioeconomic status, Black women in America are more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth. No one is speaking about this maternal health crisis we’re facing as Black women in the United States.

Secondly, we don’t focus enough on the fact that in American history, Black mothers in so many ways have not only raised their own children, but also those outside their own families. We think about slavery and Black mothers being forced to nurse white children who were not their own. There’s a large history of thinking about Black women as if they’re less than human, and I think you see that very clearly in the representation of Black motherhood in America.

Can you tell us a little bit about how you experience erasure yourself, especially as a mother?

AMT: I think I’m very sensitive to it because I studied the erasure of women and have a master’s in gender studies, so I notice it all the time. Specifically in our case especially because of my husband’s position [until recently, Michael Tubbs was mayor of Stockton, California, where he started a universal basic income program that got national attention] so many people give him so much more credit for anything in our lives.

Like with our house, they say, “This is such a nice house. Michael must have to work two jobs to afford it,” rather than assuming I also can make money. It happens in so many different ways with our child. We’ve been at events where I sit next to him, and someone walks up to him and says, “Congratulations on the birth of your son.” And I’m not someone who is quiet or reserved about these things, and I’ll say, “I wasn’t aware that Michael could give birth. That’s amazing! Congratulations, Michael.”

Then people ascribe different characteristics of our son to him. Like people saying, “Oh, wow, he’s so strong just like his dad,” or “He’s so smart just like his dad,” or “Maybe he’ll be mayor someday like his dad.” That’s a constant, and I think mothers generally experience this being taken for granted and there’s no way we’re the ones passing on strength or intellect. Hopefully, the book will inspire more conversations that change the language around that.

For your book, how do you see the mothers’ influence in their sons’ actions and speeches?

AMT: In these three cases, it’s not even a stretch. What the sons ended up doing has a direct connection to their mothers and their moms’ hopes and dreams for the future and their passions and what they were talented in doing.

Berdis Baldwin was this incredible writer who liked to write poems and wrote these beautiful letters to her family members, and even the principals at James Baldwin’s school talk about the notes she wrote to excuse his [absences] being these beautifully written documents. It’s similar to James Baldwin that even when he’s saying something so simple, it’s so poignant and it sticks with you, and he inherited this directly from his mom.

And we think about Malcolm X as this radical figure who will do whatever it takes to express the importance of Black unity and Black pride, and his mother was this Marcus Garvey Pan-African activist who believed in the self-sufficiency of our community and Black independence, so there’s direct connections between her organization she’s dedicated to and the one that became so important to Malcolm X later, the Nation of Islam.

With MLK Jr., the real connection comes because he would not have had any of the resources he had in his life had it not been for his mother. When she meets her husband, he’s considered illiterate and she already has a college degree. Her parents are the ones who have built up Ebenezer Baptist Church, so when they get married, unlike you might think, that the woman might move in with the husband, the husband moves in with her. Her family and their tradition of all going to Spellman and Morehouse, which MLK also does, and then being the leaders of the church that he then leads with his father—all that is because of her and her family.

What did you learn about motherhood from researching their lives?

AMT: Truly, I feel like I’ve learned endless lessons that continue to pop up. The one that stands out to me or that’s on my heart the most today is the mothers’ ability to be both vulnerable but also strong and their ability to teach their kids about the reality of the human experience though their own lives.

Berdis loses her father, and she’s sad in front of kids and she shows them that she experiences pain, but at the end of the day, she’s going to find that hope and that light. She shows her fear and that things are scary, but that fear wasn’t going to hold her back. It shows real human emotion and also a path forward, which I think is a beautiful lesson children should see. Every so often, mothers don’t feel they can be these real human beings, and that maybe they have to put on this air of, “I have everything figured out. I am this selfless being that doesn’t have my own needs.” I don’t think that does children any favors. Obviously, there’s a balance—you can’t fall apart all the time, but being able to be honest and vulnerable allowed these three men to be observant to what human beings were.

Why is it important to learn about these women now?

AMT: There are so many lessons to learn about what these women mean for us today, especially now that so many people are focusing on the power of Black womanhood. I feel like the book is coming at a time where there’s less convincing I have to do about the importance of Black women. We’re focused on Stacey Abrams and Kamala Harris and that incredible poet at the inauguration [Amanda Gorman], who was so beautiful and powerful. This kind of adds to that conversation if people are interested in Black American women and the ways in which we’ve influenced this nation. This is the perfect book to complement that.