Why Did a Muslim Civil Rights Group Oppose Democrats’ Plans to Confront White Nationalism?

Though compelling arguments have been made that CVE programs contribute to the marginalization and alienation of the very communities they’re meant to engage, they continue to receive significant funding from major cities, universities, and other institutions.

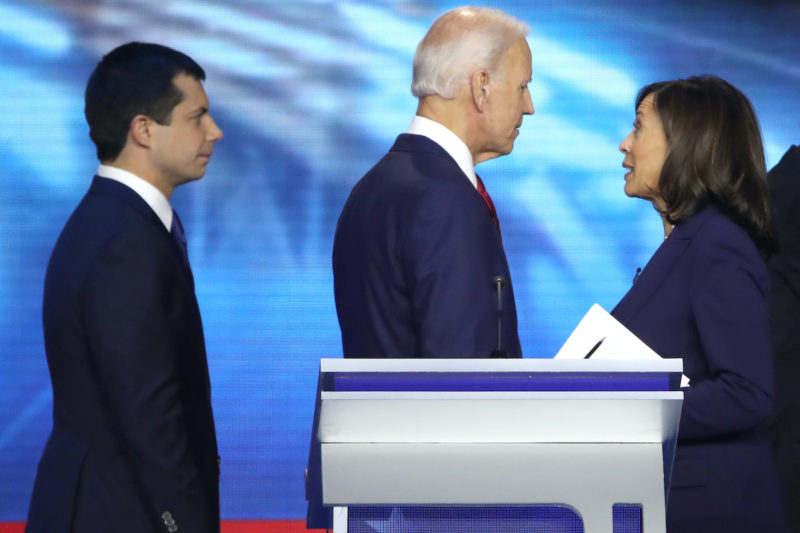

The civil rights group Muslim Advocates recently called on Democratic presidential candidates Kamala Harris and newly-minted Iowa frontrunner Pete Buttigieg to stop supporting CVE, a series of programs that aim to identify potential ‘extremists’ before they commit violence. This, despite the fact that both Buttigieg’s and Harris’ proposals focus exclusively on combatting the scourge of white nationalist violence and never mention Islam or Muslims.

Muslim Advocates explained their reasoning:

Countering Violent Extremism is a failed, discriminatory program that won’t solve the problem of white nationalist violence but will lead to increased targeting and criminalizing of American Muslims and other vulnerable communities…We have already seen what happens when CVE is implemented, including when it is implemented by a Democratic administration: American Muslims become over-policed and over-criminalized. CVE programs at their core are based on junk science that suggests someone’s race or religion can determine whether they will be more likely to commit violence. Repackaging the program to focus on white nationalists won’t change the fact that this strategy is fundamentally flawed.

In other words, even when white nationalism is the purported target, these programs focus overwhelmingly on Muslims. In theory, CVE programs aim to identify individuals at risk for becoming ‘extremists’; in reality, they promote the notion that dissent leads inexorably to violence while dividing targeted communities against themselves.

Nicole Nguyen and the #StopCVE movement in Chicago have made compelling arguments that these projects contribute to the marginalization and alienation of the very communities they’re meant to engage. And yet, even as counter-extremism initiatives have come under scrutiny, they continue to receive significant funding from, and partner with, major cities, universities, and other institutions. The Trump administration, Aysha Khan reports, has nearly tripled the amount of CVE funding awarded to law enforcement, and CVE’s advocates continue to present these initiatives as a more palatable alternative to other forms of surveillance and counter-radicalization.

The fact that CVE presents itself, time and again, as self-evidently good, even to presidential candidates who show no ill will towards Muslims, is a paradox that lies at the center of our research. Here we identify three ways to begin to “think ourselves out” of the bipartisan consensus around CVE that pervades contemporary American politics. This “3-step program” was developed in conversation with colleagues at a recent symposium held at Northwestern University.*

Conflating dissent with terrorism

CVE programming is shorthand for a family of U.S. government and government-supported programs intended to prevent terrorism. According to the Department of Homeland Security, CVE “refers to proactive actions to counter efforts by extremists to recruit, radicalize, and mobilize followers to violence.” These programs claim to deter people from becoming terrorists by partnering with local community agencies, schools, law enforcement and health providers.

While studies have shown that CVE efforts predominantly target American Muslims, such programs are part of a decades-long history in which the FBI and other agencies have conflated dissent with terrorism under the mandate of national security to target dissident communities. As Anne Barnard noted recently, “any political discussion among young Muslims about the geopolitical or social issues most pressing to them increasingly risks being labeled ‘jihadist.’”

Since 2010, as Alice Speri reports, targeted dissidents also include black activists, Palestinian solidarity and peace activists, Abolish ICE protesters, Occupy Wall Street, environmentalists, Cuba and Iran normalization proponents, and protesters at the Republican National Convention. Going back at least to the Palmer Raids of November 1919, the government has criminalized political dissent in the name of national security.

Though today American Muslims are often on the receiving end of such accusations, it’s essential to recall, as anthropologist Darryl Li points out, that “the problem of so much public discourse isn’t just about animus or ignorance toward Islam or Muslims; it’s also about antipathy toward political radicalism in general, which is so much more charged and powerful when racialized.”

CVE programs and the siege mentality that supports the War on Terror create the conditions of possibility for reframing political opposition as pathological. We need look no further than Trump-era CVE grants that target communities such as LGBTQ groups and Black Lives Matter organizations; or, overseas, the Chinese crackdown on the Muslim Uighur population as invocations of countering “extremism” that target dissenting, minority or vulnerable populations. CVE also makes it impossible to see social movements that are working hard for progressive change in the Middle East and North Africa.

In her work, anthropologist Nadine Naber explores the mutually reinforcing relationship between the move to pathologize radical politics and narratives of “saving” Muslim women and LGBTQ people. She notes that, in the case of the Middle East, “society and culture are sensationalized as horrific and must be acted upon, whereas violence enacted by the U.S. and U.S.-sponsored dictators are not even seen.” Such discourses also “obscure the wide-ranging social movements working to end patriarchy and homophobia on the ground in Muslim majority countries.”

Reinforcing a false domestic/international divide

CVE not only advertises itself as a “softer” alternative to direct surveillance but presents itself in stark contrast to “hard” U.S. counterterrorism efforts overseas. We may pursue foreign terrorists through covert action and drone strikes, the thinking goes, but at home the government respects civil liberties. Yet this false domestic/foreign divide collapses under closer scrutiny.

Ahmed Ibrahim, a professor at Carleton College, has shown that the connections between U.S.-government efforts in Somalia and Minnesota dissolve the domestic/foreign divide. The global war on terror emerged simultaneously in both places. The rise of the Islamic Courts Union in Mogadishu prompted the invasion of Somalia by Ethiopian fighters, with the backing of the US, and the Somali community in Minnesota was subsequently targeted both as a potential security threat and a source of potential support for U.S. nation-building efforts in Somalia.

Similarly, American methods of surveilling Muslims are now being exported to China in a global commodification of anti-Muslim policies and practices. The Nigerian government used Trump’s words calling for lethal force against rock-throwing migrants to justify killing rock-throwing Shi‘i protesters. War on Terror rhetoric has fueled indiscriminate massacres of Fulani villagers in Mali, simply because al-Qaeda’s branch in Mali has drawn heavily from ethnic Fulanis. Connecting these “two faces” of the U.S. experience is a continuing challenge, and also requires unthinking CVE.

Why have these connections gone unnoticed? The War on Terror, while often viewed more critically today in terms of failed U.S. efforts abroad, doesn’t seem to have generated the same level of skepticism when it comes to anti-terrorism efforts at home, which has enabled CVE to flourish.

Phobias and philias

Unthinking CVE also requires paying attention to the terms of inclusion of American Muslims in public life. The anthropologist Andrew Shryock uses the term Islamophilia to describe the “good Muslim” caricatures to which liberal discourse expects Muslims to conform. If Islamophobia sees Muslims as jihad-waging foreigners, Islamophilia sees them as peace-loving, apple-pie-baking neighbors. Or, more precisely: this is who they must be to be included.

But Islamophilia can also perpetuate the interests of American militarism: American Muslims’ military service and love of country become prerequisites for inclusion. The terms of such inclusion were never laid out more clearly than by Bill Clinton at the 2016 Democratic National Convention: “If you’re a Muslim and you love America and freedom and you hate terror, stay here and help us win and make a future together, we want you.” These caricatures come with distinct political costs that are often more subtle—and therefore often more damaging—than Islamophobia’s caricatures.

The term ‘Islamophobia’ itself is also inadequate. Are anti-Muslim people really ‘phobic,’ or are they acting out powerful narratives that are validated and sanctioned by governments, the media, and well-funded anti-Muslim advocates? Further, singling out hatred of Islam or Muslims as the problem, and attempting to disentangle it from larger questions of citizenship, inclusion/exclusion, race, and inequality, risks losing sight of the bigger picture.

For example, treating Presidential Proclamation 9635 (the ‘Muslim ban’) solely as ‘Islamophobic’ obscures the broader institutionalized and legalized forms of discrimination that makes the ban possible in the first place. The power to discriminate at the border is enjoyed by all American presidents, not just Trump. Could we imagine creating effective checks on the indiscriminate power of the executive to do anything in the name of national security, including policies that foment hatred and division?

Recent scholarship has explored the many ways Muslims are pressured to make Islam legible to American (read: Protestant, secular, white) sensibilities. In Islam: An American Religion, the French political scientist Nadia Marzouki uses the term “formatting” to describe how Muslims in the U.S. are pressured, often by would-be liberal allies, to represent themselves as quintessentially “American” and to represent Islam as fundamentally “spiritual” (i.e. apolitical and non-threatening). American Muslims are pressured to “format” how they practice Islam around American ideals. CVE is one of the primary ways this is accomplished.

At this point Pete Buttigieg and Kamala Harris are unlikely to walk back their commitments to CVE. Perhaps the most we can hope for is more awareness on their parts of the dangers of blindly subscribing to policies and programs that quietly reinforce Trump’s white power agenda.

*This symposium was convened with the support of the Luce/ACLS Program in Religion, Journalism, and International Affairs.