Elizabeth Warren’s Student Debt Plan: An Outsized Economic Boon for People of Color

The dramatic rise in student debt has placed unacceptable risk on working-class families and on people of color, who must take on more debt for the same degree as white students.

![[Photo: A group of students of color do late-night research at library.]](https://rewirenewsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/students-of-color_3-800x533.jpg)

Presidential candidate U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) this week unveiled an ambitious plan to make college free, expand Pell Grants for students with low incomes, and cancel student loan debt for most borrowers, including around 8 in 10 Black and Latinx people.

This marks the first time that mass student debt cancellation has been proposed as a serious, presidential campaign-level topic. It’s also one of the first mainstream plans that would provide massive help to families while potentially narrowing our nation’s persistent and shameful racial wealth gap.

Warren’s plan, announced in a Medium post, is as follows: Everyone would receive free public college at two- or four-year schools with a massive expansion of Pell Grants for low-income and middle-class students to help pay for living costs and other expenses that make up the majority of borrowing. It is effectively both a guarantee of free college for everyone and a guarantee of debt-free college for students with low income. The plan would cancel up to $50,000 in student loan debt for families making under $100,000 annually, with a sliding scale of forgiveness for those making between $100,000 and $250,000.

Economists estimate that 80 percent of Black households with debt and 83 percent of Latinx households with debt, would see it eliminated entirely. The vast majority of low-income and middle-class households would see their debt forgiven, compared to about a quarter of families from the top 10 percent, according to Warren’s estimates. And while slightly more dollars would flow to upper-middle-class households, the impact of canceling all debt for low-wealth households cannot be overstated. It removes a serious level of risk, allowing for peace of mind and the ability to get out from under financial strain.

Reducing or eliminating the need to borrow at public colleges through the expansion of Pell Grants to cover things like fees, living costs, books, and childcare offers a pathway to college without any debt for those who are currently most likely to borrow and struggle to repay their loans. It links the simplicity of tuition-free college with the progressivity (and concern about non-tuition costs) that debt-free college advocates endorse. It expands funding for Historically Black Colleges and Universities that, due to centuries of structural racism, do not have the same resources as predominately white institutions.

Indeed, the dramatic rise in student loan debt has placed unacceptable risk on working-class families and on people of color, who must take on more debt for the same degree as white students and often need to gain several levels of education just to maintain a foothold in the middle class.

Despite the federal government trying to make student debt payments more manageable (by creating repayment plans that align borrowers’ monthly payments with their income), the percentage of student loans that are 90 or more days delinquent has remained essentially unchanged since 2012, even as unemployment has fallen and the economy has generally improved. Default rates are appallingly high on student debt, particularly among black borrowers. Middle-income Black households are the most likely group to be delinquent on student loans. And borrowers of color find it basically impossible to chip away at both the principal and interest on their debt.

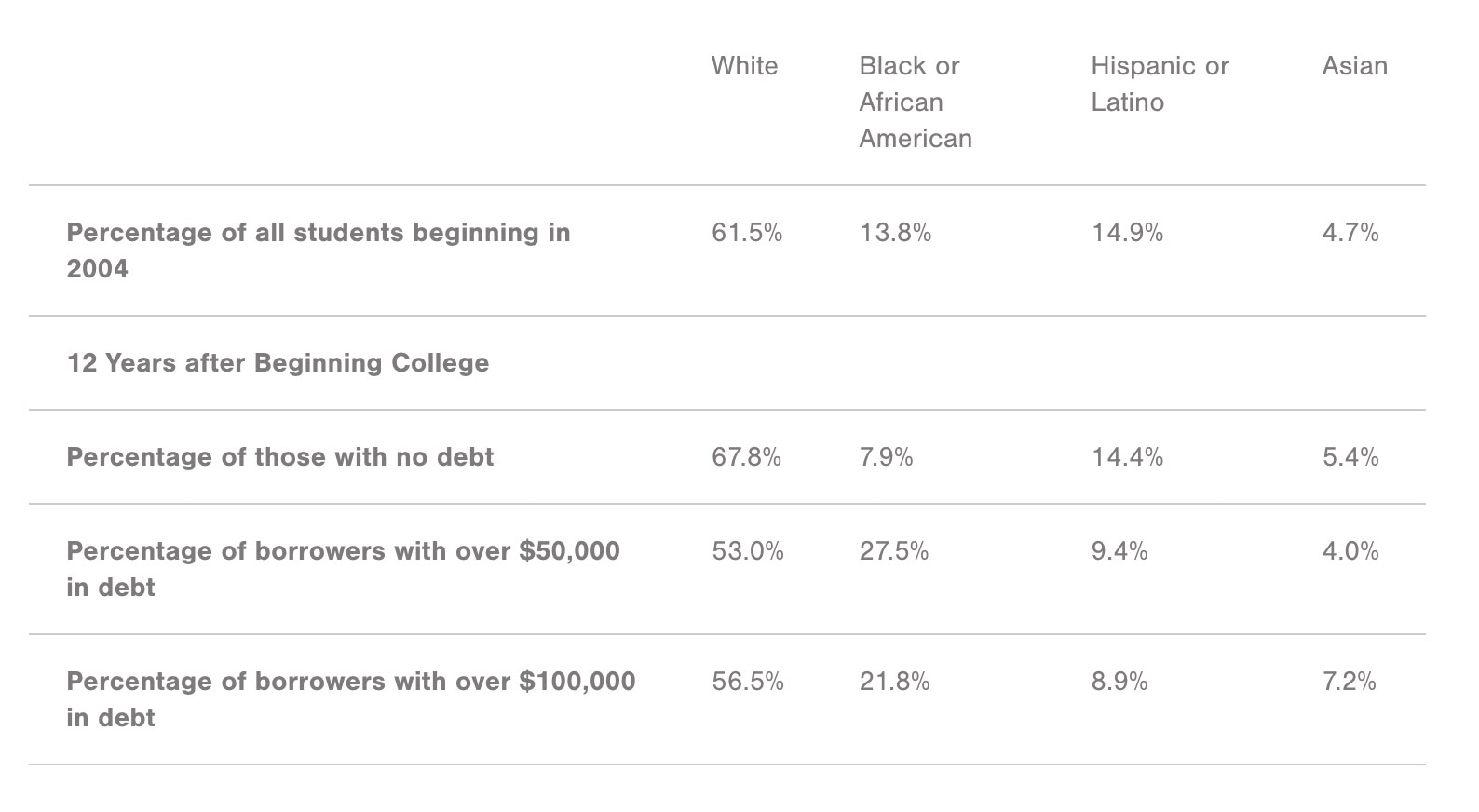

Rather than fixing loan repayment, actually canceling a portion of everyone’s debt—Warren proposes forgiving $50,000 of debt for families making under $100,000 a year, with a sliding scale of forgiveness for wealthier families—could substantially address the racial disparities inherent in student loan borrowing. Black borrowers are overrepresented among those who have large debt. Twelve years after beginning college, Black borrowers make up less than 8 percent of those with no debt, but over a quarter of those who hold over $50,000 in debt.

Black Students are Overrepresented among Those with Large Debts 12 Years after Starting College

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2003-04 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, Second Follow-up (BPS:04/09). Data for American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and other students not available due to sample size issues.

There are large populations who have attempted college for whom it did not pay off. Among families receiving means-tested assistance, 11.6 percent had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and an additional 31.8 percent had at least some college or an associate’s degree.

This shift in the policy conversation is striking. For many years, the policy consensus around addressing student loan debt centered on making the debt easier to repay, targeting forgiveness at those who had been harmed by bad actors, preventing those bad actors from accessing federal loan dollars, and holding loan servicers accountable. All of these were and are noble goals, but all of them were predicated on the notion that student debt problem is a consumer protection problem, that student debt was fundamentally “good debt,” and that as long as higher education resulted in greater earnings than high school, debt was justified for most.

We continue to justify student debt on the assumption that the United States suffers only from a college completion crisis, despite the fact that over 20 percent of Black bachelor’s degree recipients default on their loans.

The new conversation, which Warren’s policy has helped jump-start, is based on a deeper question about whether it is either moral or efficient to force people into borrowing massive amounts of money for education—particularly an undergraduate education, and more particularly an undergraduate education at a public two- or four-year college. It also asks: What do we do when one of our social safety net programs (in this case, federal student loans) causes disproportionate and extensive harm to certain communities? Should we continue to make the program simpler and fairer, or should we essentially start from scratch?

There are important details to work out. Ensuring states continue to reinvest in public higher education is crucial, as is finding the right level of investment that states can maintain given competing priorities.

It’s important to create a tuition-free, or debt-free, policy that survives a recession when state budgets are squeezed and demand for education rises. We should ensure that Pell Grants address the rising cost of non-college expenses, from housing to childcare. We should work to address inequity within public higher education, not only by reducing the financial burden of attending but by making sure selective public colleges are available to all students and not just a wealthy, white few. And since this plan would not eliminate all debt—there are still some middle-income families, for example, who have more than $50,000 in debt—we should think about how to address repayment and other mechanisms for the borrowers who remain. Finally, we should think about how our safety net addresses those who have recently paid off student debt but still may be struggling financially.

But it is refreshing to see student debt cancellation being taken seriously and being done with an eye toward addressing inequality. It’s important to recognize that many people struggling with student loan debt did nothing but follow their dreams and educational aspirations and that many of them should be given a chance to move on with their lives.

This article originally appeared on Demos.org.