The Forgotten History Behind Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Terrorism

When we fail to remember our plural origins in the West, we help white terrorists erase our own history.

In addition to anti-Black racism and anti-Semitism, one of the pillars of the contemporary global white terrorism movement is anti-Muslim hatred.

That hatred is founded on a kind of forgetting, an historical erasure.

This forgetting can be seen in the ideologies of Anders Breivik, the Norwegian terrorist who murdered 77 people in 2011, and Brent Tarrant, the suspect in the murder of 50 Muslims in Christchurch, New Zealand.

The erasure is a result of the assumption that Muslims are foreign to the West. Such forgetting leads to madness, the same madness that inspired Don Quixote to joust with windmills in a post-Reconquista Catholic Spain where everyone swore that Jewish and Muslim cultural influences had been eliminated.

This is not to dismiss that a significant number of people believe that immigrants pose a threat to the cultures of the West. The immigration of Muslims and other minoritized religious groups to white, Christian-majority countries such as New Zealand, the Netherlands, and the United States have clearly engendered negative reactions and often nostalgia for a more homogenous society.

But when those feelings become the lens through which we rehearse a white supremacist, imperial narrative of Western history, we deprive ourselves of a past that can help us reimagine our present.

In truth, the West as we know it wouldn’t exist without the contributions of Muslims. It’s time to unearth this buried mirror so that those of us who live in the West might see ourselves more accurately.

Muslims have been part of Western history since 711 CE, when Muslims established a state in Andalusia. It is true, as anti-Muslim activists like to point out, that Muslim-led armies sometimes attacked Christian-led armies in medieval Europe. But what they perhaps willfully omit is the fact that Muslims were as likely to fight for and with Christian-led European militaries as they were against them.

The military history of medieval and modern Europe is as much a story of Christian-Muslim cooperation as conflict. For example, in the taifa period of Spanish history from the 11th to the 13th century, when there were several small principalities vying for political control of the Iberian Peninsula, Christians often served in Muslim armies and vice versa.

Religion was no impediment to military service.

Though the Muslim Ottoman Empire clearly sought to expand its territory in Europe, where it became one of several European powers jostling for territories, it also sought Christian allies. In 1453, for example, Ottoman admiral Barbarossa, an Albanian, helped French King Francois besiege the forces of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in Nice. Thousands of Tatar Muslims helped to fight for Poland in the Battle of Warsaw in 1656, and in 1791, the Polish Constitution granted them representation in the parliament.

In 1853, Muslims fought for their respective countries in the Crimean War, and they would go on to serve the allies in World War I and World War II—by the hundreds of thousands.

But Muslims did much more to build the West than serve in its armed forces.

Medieval European scientific advances in optics, pharmacology, chemistry, medicine, algebra, astronomy, trigonometry all depended on the discoveries of Western and other Muslims. The medical research of Al-Razi (Rhazes) and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), author of The Book of Healing, were used to teach medical students in Europe for centuries.

Medieval Christian theology was born in a conversation with Muslim theologians such as Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Ibn Rushd, or Averroes. Averroism was condemned at the University of Paris in 1270 but it was in refuting its explanations of the origins of the world and the nature of the human soul that the theology of Saint Thomas Aquinas was made.

Northern Europeans flocked to the libraries of Southern Europe to read the hundreds of thousands of volumes in libraries such as that of 9th-century Corboba. New vernacular poetry was inspired by Arabic, a shared language among Jews, Christians, and Muslims, which also became the official court language of the Norman King of Sicily, Roger II, during the 1100s.

Even after 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella conquered Granada, the last remaining Muslim principality in Iberia, Spanish colonizers would bring the architecture of Muslim Spain to the Americas. From the Caribbean to the California coast, tile patterns and rectangular open courtyards are Muslim legacies of our shared Western experience.

The contributions of Muslims to the building of modern Western nations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and France are just as important.

It was U.S. Muslim writers and thinkers such as Mahommah Baquaqua and Mohammed Ali ben Said, who also served in the Massachusetts 55th (Colored) Infantry during the Civil War, that gave American readers some of their first accurate accounts of African cultures. North Carolinian Omar ibn Said penned the first extant Arabic-language memoir of American literature in 1831, a document recently digitized by the Library of Congress. These three writers were among the tens of thousands of enslaved African-born Muslim men and women who literally helped to build the United States from 1776 to 1865, when legal slavery was formally ended.

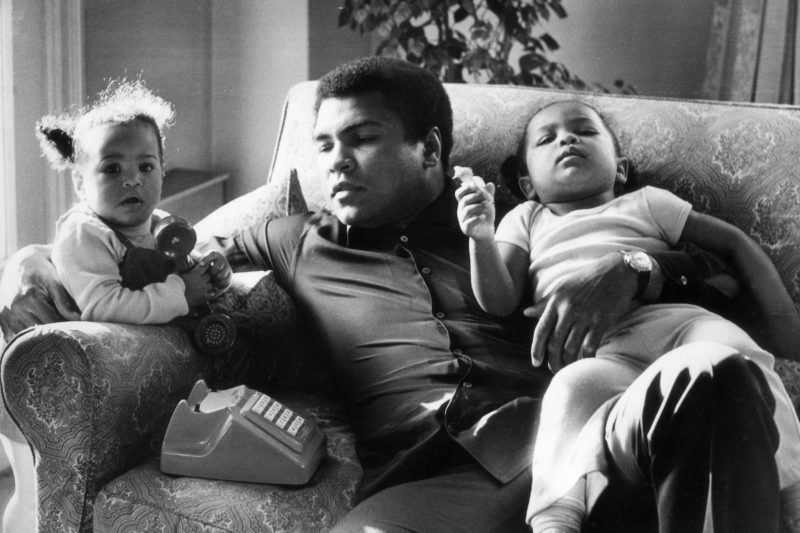

The 20th century is so full of Muslim contributions to Western literature, music, art, sports, politics, business—every realm of life in the West—that some household names should suffice to illustrate the point. In jazz, Ahmad Jamal, Art Blakey, Dakota Staton. In sports, Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Zinedine Zidane, Ibtihaj Muhammad. In architecture, Fazlur Rahman Khan. In chemistry, Ahmed Zewail. In higher education, Amina Wadud, Leila Ahmed, Saba Mahmood, and so many others. Such names need to be learned and repeated to counter the lie that Muslims are not part of the West.

When we fail to remember our plural origins in the West, we help white terrorists erase our own history. Naive comments about the “newness” of Muslims in the West need to stop. Right now. Everyone who adds to rather than challenges this historical forgetting has a duty to relearn Western history. It’s a matter of life and death. Not just for Muslims in the West, but for everyone who values the truth.