New York Governor Cuomo Should Not Play Politics With Black Maternal Health

In an election year that will determine whether the political tides will change, advocates are wary of empty promises to address racial disparities in maternal health.

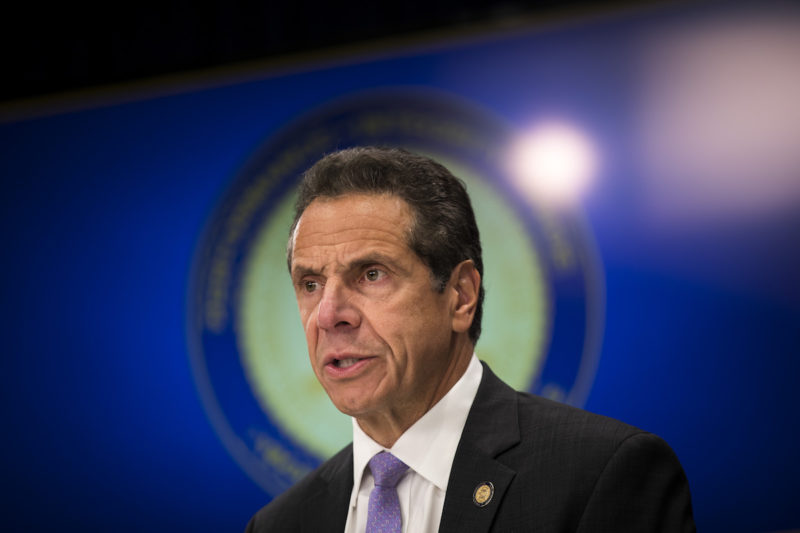

Shortly after the very first national Black Maternal Health Week, founded and led by the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) announced his intentions to address high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity among Black women in New York state. The comprehensive initiative includes an expansion of Medicaid coverage for doulas, reducing the out-of-pocket costs for what is often life-saving care for low-income families.

On April 22, the New York Times reported that “the design of the doula pilot program will be finalized by the state’s Health Department within 45 days, and the program will start immediately thereafter.” But 45 days have long come and gone and, despite launching a task force, the New York State Department of Health still has no solidified program plan or a launch date to begin implementation.

In an election year that will determine whether the political tides will change, advocates are wary of empty promises to address racial disparities in maternal health. Gov. Cuomo shouldn’t play politics with Black maternal health. Rather, the governor should let New York state be the example the United States needs by getting doula Medicaid reimbursement right. Now.

New York has the opportunity to implement a successful Medicaid program where other states—like Oregon and Minnesota, the only other states to allow Medicaid reimbursement for doulas—have fallen short. In Minnesota, a low reimbursement rate and oversight requirements for doulas have hindered implementation.

New York can start with prioritizing the participation of community-based doulas who center Black women in their work in the Medicaid reimbursement program. To truly address Black maternal health, the New York Department of Health must invest in Black women’s maternity care work.

Community-based doulas, who typically serve low-income Black and Latinx women who would otherwise go without doula care, provide culturally relevant and holistic care in communities with the greatest need—often while under-resourced and overlooked by state and city officials looking for solutions to problems when those solutions may be right in front of them. Doula care in general has been associated with a lower likelihood of medical interventions during birth and cesarean section, reductions in complications, shorter labor, lower preterm birth rates, and a reduced likelihood of a low-birth weight infant. Doula care is also associated with higher breastfeeding intention and initiation. Community-based doulas go beyond birth work and lactation support to help their clients navigate various social and economic barriers to good birth outcomes.

Brooklyn-based Ancient Song Doula Services recently launched the campaign #BeyondBirthWork to explain the role of community-based doulas in reducing racial disparities in maternal health outcomes, and to organize support for their inclusion in the New York state doula Medicaid pilot program.

Evidence shows that community-based doulas, who come from the communities they serve, take on roles akin to social workers, health care and education advocates, sexual health educators, and health systems navigators. These doulas help their clients with their social and nonmedical needs and, in doing so, help address socioeconomic and racial disparities. New York City’s By My Side Birth Support Program provides free access to doula support to birthing Black and Latinx parents and in high-poverty neighborhoods. A study of the program shows clients have benefited from emotional, informational, and social support. The study concluded that the program could help address inequities in birth outcomes.

Chanel Porchia-Albert, founding executive director of Ancient Song Doula Services, knows that Black community-based doulas provide a holistic model of care that meets client needs and advocates for a shift in the health-care system. “In order to effectively address racial disparities of Black women within reproductive health, the current system needs to move from its prototype of care that does not incorporate community and nontraditional care providers as active stakeholders,” Porchia-Albert said. “Our culture of care must move in a direction that actively centers the pregnant person and understands the intersectional needs of that community.”

At least two studies have found that matching birthing parents to same-ethnicity doulas contributes to better maternal health and birth outcomes. In Minnesota, 92 percent of Black Medicaid clients with doula support initiated breastfeeding compared to 70 percent of the general Medicaid population. That study’s authors concluded that culturally appropriate doula care, ethnic concordance between doulas and clients, and nonmedical support offered by racially diverse doulas may increase the likelihood of breastfeeding initiation. Also in Minnesota, researchers found that a program training Somali women to serve as doulas for other Somali women reduced cesarean section rates and increased confidence among hospital nursing staff who had worked with Somali doulas. In this case, same-ethnicity doulas helped bridge cultural and ethnic divides between their clients and hospital staff.

Furthermore, Black women-led models of care have been proven to reduce racial disparities in maternal health and birth outcomes and help improve Black maternal health. For example, The JJ Way client- and community-centered model of care, founded by midwife Jennie Joseph, provides culturally relevant care that is shown to eliminate racial disparities in preterm birth and low birth weight.

If New York state is to make improvements in Black maternal health and reduce racial disparities—changes it desperately needs—it must prioritize the leadership of Black women-led models of care. This requires the elimination of barriers to Black doulas’ involvement in the Medicaid pilot program. Appointing Black women-led doula organizations as program implementers, setting fair and livable reimbursement rates, and easing the reimbursement process can help ensure that Black community-based doulas can utilize the reimbursement program to help Black birthing parents thrive.

First, appointing Black women-led doula organizations as implementers of the program can help the health department reach its intended goals of reducing poor outcomes among Black birthing parents. Black women-led doula organizations, like Ancient Song Doula Services in Brooklyn and Village Birth International in Syracuse, provide culturally relevant care that helps to mitigate the effects of racial discrimination and implicit bias. “When you trust Black women-led organizations in facilitating that care, you are not only investing in that organization, you are shifting a paradigm towards the healing of a community and actively dismantling racism within the health-care system,” said Porchia-Albert.

Additionally, investing in existing models of care that serve Black birthing parents to help them expand their services could go a long way. Financial investments would facilitate the training of more doulas from low-income communities. Doula training can cost up to $1,200, an expense that is unaffordable for many people from low-income communities.

Even after being trained, some doulas find they are unable to make a career out of being a doula. In Oregon, the standard doula reimbursement is only $350 total for two prenatal visits, support on the day of delivery, and two postpartum visits. In Minnesota, the standard reimbursement is slightly higher at $411. Shafia Monroe, a midwife based in Oregon and founder of the International Center for Traditional Childbearing, says a $1,000 reimbursement is more ideal but acknowledges that having reimbursement at all is a success. “The fact that Medicaid reimbursement for doulas is in place is a win. Now, a doula who was helping her friends for free is at least getting paid $350,” Monroe said.

Paying doulas a living wage under the Medicaid reimbursement program is critical. Asteir Bey, founder of Co-Mothering Syracuse and co-director of Village Birth International, says community-based doulas have struggled to make ends meet and provide services. “Doulas serving birthing people in their own community struggle to do so while sometimes maintaining full- or part-time employment and tending to the needs of their own family in low-resourced communities. And despite reducing death and illness for birthing people engaged in doula care, community-based organizations have struggled to expand services to the women who need it most due to lack of funding,” Bey shared. “Medicaid reimbursement that provides a true living wage by compensating full spectrum doula care and the range of services provided is essential to the success of the program in New York state.”

Gov. Cuomo should not only prioritize setting a livable reimbursement rate, but he should ensure the program reduces administrative burdens and allows doulas to be reimbursed under a group model rather than requiring they get reimbursed as individuals. At the individual level, the administrative effort to manage all the necessary paperwork for Medicaid reimbursement could prevent some doulas from participating.

At the end of the day, New York state must do what it can so that at-risk people get the care and support they need through a sustainable model for care providers. “Families who receive Medicaid should be able to access doulas,” Monroe emphasized. By supporting Black doulas’ participation in Medicaid reimbursement, the New York State Department of Health can help families who need it most receive culturally appropriate care.

What remains to be seen is if the governor will follow through on his promises. The state is currently gathering recommendations from appointed task force members, but there are no clear plans to launch the pilot program before 2019. Gov. Cuomo should set aside his political motivations and do what he can now to follow through on his promises and address Black maternal health by prioritizing Black women-led efforts.