‘The Ultimate Form of Voter Suppression’: D.C. Council Axes Pro-Worker Ballot Initiative

The vote came after the D.C. Council was flooded with money from the restaurant industry, which has fought measures to increase the tipped minimum wage in cities across the United States.

The D.C. council this week voted to overturn a ballot measure approved by district voters, including outsized support from people of color and those living in higher-poverty areas, that would have ensured that tipped workers be paid the same minimum wage as all others.

The tipped wage in the district is $3.89 an hour, but would have eventually been increased by 2026 to meet the regular minimum wage, which, under Initiative 77, would have been $15 an hour for all non-tipped workers by 2020.

The vote came after the council, particularly council Chair Phil Mendelson, was flooded with money from the restaurant industry, which has fought measures to increase the tipped minimum wage in cities across the United States. A Public Citizen analysis of the money donated by the individuals and entities that either signed a public letter opposing Initiative 77 or contributed to the two main committees against it, Save Our Tips and NO2DC77, found that they gave $236,013 during the two most recent city elections. The council members who voted in favor of overturning it last week got $140,713 collectively, while Mayor Muriel Bowser, who was against Initiative 77 and has said she’ll sign the repeal bill, received $65,050.

The National Restaurant Association, which represents the largest companies in the food service business and struck a deal in 1996 to keep the federal tipped minimum wage frozen at $2.13 an hour, has been the largest donor by far to Save Our Tips. The restaurant lobby presented Save Our Tips as a grassroots group of restaurant workers opposed to raising the tipped wage.

Meanwhile, restaurant workers in favor of the initiative struggled to be heard. According to Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United, which was behind the measure, around 100 tipped workers and other supporters in favor of abolishing the tipped minimum wage showed up at the John Wilson Building to testify before the council in September. Only three were able to speak within the first three hours, even as the council heard from several dozen people speaking against the measure. Most tipped workers and supporters in favor of it weren’t called until after 5 p.m., at which point many had already left.

Dia King, a valet attendant, wasn’t called to speak until after 2 a.m., even though she had to be at work at 7 a.m. the same day. Trupti Patel, a restaurant server, stayed 18 hours to testify in favor of Initiative 77.

Then there are the restaurant workers who ROC argues wouldn’t feel safe showing up: those who don’t speak English and those who may have immigration status issues who aren’t comfortable speaking to government officials. “Even if you were born here and understand your rights, if you have two or three jobs am I going to ask a member, ‘Hey, come sit with me for 16 hours in a city council building?’” said Diana Ramirez, director of ROC-DC.

Despite that, Mendelson claimed at the hearing that he hadn’t “heard from anybody” that they supported Initiative 77 but struggled to speak out.

The issue came up during the vote on repeal. During debate, Councilmember Elissa Silverman, who voted against overturning Initiative 77, said the debate has raised “an important question of who gets to speak and who is listened to at the Wilson Building, as well as who was not speaking who we’re not hearing from.”

“Voters in general are feeling so disenfranchised, so powerless,” Ramirez said. She predicted that the ripple effects of the council’s action will extend beyond undoing Initiative 77. “The division that this overturn is going to create in the city will outlast Initiative 77,” she said. “The harm that’s going to be done will be felt throughout the district for years to come.”

People who came out and voted in favor of the initiative may now second-guess whether the council will listen to their desires if it clashes with the wishes of industry. “Overturning the vote is the ultimate form of voter suppression,” Ramirez said. “What is the incentive for folks to come out next time when you’ve proven to them that their voices don’t matter?”

The people whose votes were voided by Mendelson and his council colleagues look a lot like those who work in the restaurant industry: yes votes were highly correlated with a ward’s poverty rate and share of the Black and brown population. Restaurant workers are disproportionately likely to be people of color and to live in poverty.

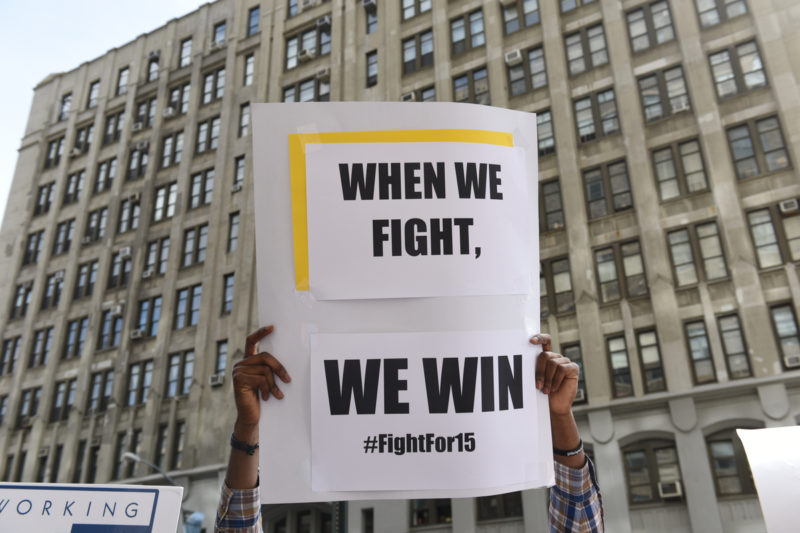

The repeal isn’t final yet: It still has to pass a second, final vote later this month or in early November. ROC members and supporters plan to demonstrate when that happens.

If it does indeed get fully repealed, it’s still too early for ROC officials to know what they will do next. But it does know one thing for sure: It’s not done fighting. The organization is regrouping and consulting with its members and supporters to figure out the smartest path forward. “It has to be strategic,” Ramirez said. It has to “be a pathway to gaining more power for restaurant workers in the district .… What is clear is that restaurant workers and constituents don’t have the same power as the restaurant association does … so we have to continue the fight with something that’s equally strong and that’s equally powerful.”

In the next few months, ROC will decide its next steps, which it will then roll out over the following years.

Some of the options include putting forward a referendum on the issue, which wouldn’t create a new policy like the original initiative but change an existing one; staging a recall campaign against councilmembers who voted for repeal; and helping tipped workers run for office themselves under ROC’s political activity arm. “We just have to identify what is the best strategy, what’s the best timeline,” Ramirez said.

One way or another, ROC is vowing to continue. “There have to be consequences,” Ramirez said. “That’s the message they need to hear loud and clear: You can’t just do whatever you want to do, can’t just do what your campaign donors … tell you to do. We’re the ones who vote you in.”

“It’s not a matter of if we come back. It’s a matter of when and how,” she said.