In Canada, Ontario Premier’s War on Sex Ed Sows Confusion and Sparks Protests

The province's top leader says a 2015 curriculum's discussions about gender, sexuality, and internet safety were too much and too soon for younger students. Some parents and students disagree.

Earlier this year, voters in Ontario, Canada, elected the right-wing Progressive Conservative Party into power, making controversial populist Doug Ford the province’s premier.

Ford ran on a platform promising to overturn Ontario’s sex education curriculum, which had been implemented in 2015 by the previous Liberal government. He claimed that it was too radical, did not respect parents, and taught about sexuality and gender identity “too early.” Soon after taking office, he announced that the current curriculum would be scrapped and that parents could report noncompliant teachers—those still teaching the inclusive, newer curriculum—through an anonymous phone line.

Over the summer, schools received what Toronto-based sexuality educator Nadine Thornhill described as “a series of vague and problematic directives” that came from the Ministry of Education and raised more questions than they answered.

First, what was being repealed? Was the repeal for all grades or elementary schools alone? And were schools supposed to eliminate the entire health and physical education curriculum or just the part pertaining to sexuality?

Then, Thornhill explained, came an announcement that, even without a curriculum, there could be classroom instruction on gender and consent. That announcement was quickly followed by an about-face in which teachers were told they couldn’t teach about these topics but that if student questions on them arose, queries should be addressed with the individual student.

Confusion reigned until right before school started in earlier this month and when some clarification finally emerged: High-school teachers could continue to use the 2015 version of the health and physical education curriculum. Kindergarten through eighth grade teachers, on the other hand, were instructed to use an interim health and physical education curriculum that came out in 2010 but which included sexuality content written in 1998.

The targeted Health and Physical Education curriculum had been updated in 2015 to reflect important social changes. It increased focus on gender identity and sexual orientation, and it expanded lessons on pornography, sexting, and digital citizenship. It also included discussion of topics like puberty, sexual violence, and consent in earlier grades.

These changes were welcomed by teachers. A 2017 survey conducted by University of Toronto Professor Lauren Bialystok found that almost all of the 150 respondents (including teachers in public, private and Catholic schools) felt positively about the curriculum and reported it to be user-friendly, relevant, and inclusive.

That support was further demonstrated earlier this month when lawsuits seeking to prevent the curricular rollback were filed, not only by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, but also by the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario.

It still is unclear just how this support will play out. Sexuality educator Karen B.K. Chan said many schools are grappling with their response.

“Many organizations and schools that I work with have decided to depart from the politicking of the curriculum altogether. The truth is, regardless of the curriculum, schools are having to respond to real-life issues that the 2015 curriculum addresses. They don’t have a choice to avoid topics like internet safety, porn literacy, social media etiquette, online bullying, sexual consent, gender diversity, and trans inclusion.”

The parent backlash against the repeal has also been significant. A group called People for Ontario’s Sex-Ed Curriculum has organized actions in support of the 2015 curriculum and has taken to social media to encourage parents to voice their opinions.

Many of these parents share views like those of David Reichert, who has 6- and 10-year-old daughters in Toronto public schools. He said, “My biggest concerns are around the safety of the children. I feel that repealing the 2015 curriculum will leave them more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Not only by adults but also by their peers.”

Jodi Rice, a parent of a child in third grade, echoed these fears. “Ignorance is dangerous in this case. There will be bullying of LGBTQ kids because of ignorance. There will be suicides by youth of all kinds—queer, gender non-conforming, raped, pregnant, slut-shamed—that could be prevented if we can prevent ignorance.”

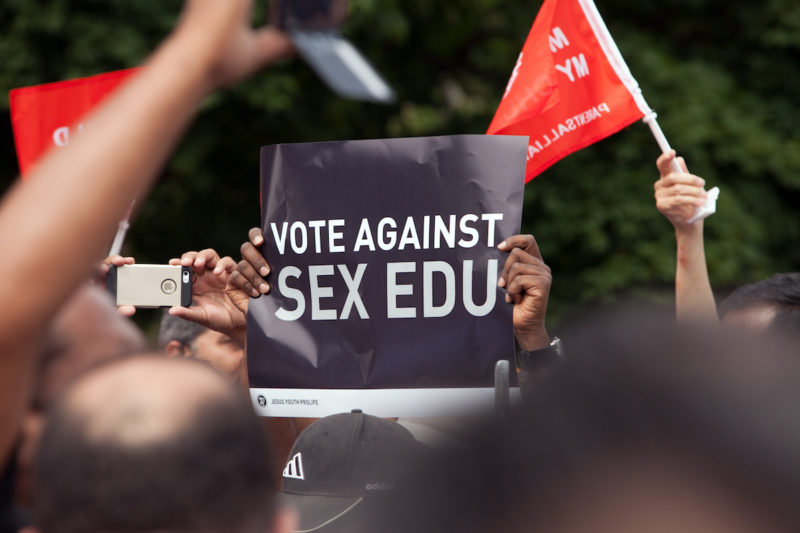

Many of Ontario’s students have taken to social media and the streets to support the 2015 curriculum. On September 21, students from across the province participated in a walkout in protest of the curriculum rollback.

They face formidable opposition, much of it also on social media. For example, Jordan Peterson, a University of Toronto psychology professor, took up the anti-sex ed mantle. Peterson claimed comprehensive sexuality education promoted a “social constructionist view” of gender identity and called it a form of indoctrination. In a tweet to his 860,000 followers, he cautioned: “Parents: these words (particularly together) mean indoctrination: ‘diversity, inclusivity, white privilege, gender’ and, above all, and absolutely unforgivably & ‘equity.’ Never, ever let teachers talk to your kids about equity.”

Another opponent, former marketing and fundraising worker Queenie Yu, created a one-issue political party in 2016. Though not a parent herself, Yu declared that she had unofficially adopted all the children in Ontario and was fighting against sex ed on their behalf. The party, called Stop the New Sex Ed Agenda, ran three candidates in the 2018 Ontario general election. None of them won their seats, but their campaigns helped draw attention to their issue.

Conservative groups like the Parents Alliance of Ontario painted the curriculum as something that offered specific instruction in sex, was anti-family, and was age-inappropriate. They also erroneously alleged that it had been developed without community input.

These arguments failed to acknowledge that since the rollout of the 2015 curriculum, Ontario schools have had policies giving parents some latitude in their children’s participation in sex education. These typically offer religious or other opt-out accommodations for some curriculum content about gender identity and sexual orientation.

Lyba Spring, who spent 30 years working for Toronto Public Health before becoming an independent sexuality educator, explained another way to engage with parents. “One strategy regarding parents’ questions and concerns about sex ed classes was to get the parent council to invite me to the school to talk about raising sexually healthy children and to explain what the children would be learning and why. Generally, this strategy worked to allay their fears and respond to their concerns.”

Sex ed educator Thornhill has had similar experiences. She said, “I’ve done a lot of parent education, and the ministry provides material that can be sent home to parents to let them know what is going to be taught.”

Since the 2015 curriculum was rolled out, those materials included a parent’s guide explaining the need for the curriculum, how it applied to students of different ages, and what additional support parents could offer.