Confusing and Onerous Work Requirements Lead to Loss of Medicaid Coverage in Arkansas (Updated)

“The assumption of personal responsibility that is underlying this policy doesn’t necessarily take into consideration the challenges people are facing on a daily basis," said Jessica Greene, a health policy professor.

UPDATE, March 28, 10:29 a.m.: Federal District Court Judge James E. Boasberg on Wednesday blocked Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas and Kentucky, the New York Times reports.

Thousands of Medicaid recipients in Arkansas have lost health coverage for the rest of the year after failing to meet the state’s new Republican-backed work requirement. Some don’t have health care today because they never knew about the stringent rules.

Jessica Greene, a health policy professor at the City University of New York’s Baruch College, interviewed 18 Medicaid recipients in northeast Arkansas in mid-August and reported a lack of awareness about the policy. Twelve of the 18 people Greene interviewed did not know about the new work requirement. Many of the Medicaid recipients didn’t know how to report their satisfying of the work requirement online.

“A lot of people had very little understanding about the policy,” Greene told Rewire.News. “I expected people would be overwhelmed by the online reporting, but people kept saying, ‘I know nothing about it and no one I know has said anything.’ There was a lot of confusion.”

According to a report from the Urban Institute, 78 percent of the Arkansas enrollees subject to the work requirement have at least one of the following attributes: no access to a vehicle in their household, no access to the internet in their household, less than a high school degree, a serious health limitation, or a household member with a serious health limitation.

In June, Arkansas became the first state to implement a work requirement for Medicaid recipients. Out of about 26,000 people who became subject to the requirement, 4,574 failed to meet the reporting deadline of September 5, the Arkansas Democrat Gazette reported. Twenty-one percent of people in Arkansas receive Medicaid benefits.

“The more people we have in insurance coverage, the better off we are long-term and the better health care costs are overall,” said Jodiane Tritt, executive vice president of the Arkansas Hospital Association, which represents 106 hospitals in the state. “Arkansas hospitals provide about $360 million in uncompensated care a year. We are concerned about those numbers increasing.”

September 5 marked the first three-month reporting deadline since the GOP-backed policy rolled out in June, and due to technical difficulties, the deadline has been extended to October 5 for those who had problems accessing the reporting website, according to the Arkansas Department of Human Services (DHS).

The work requirement, long a goal of Republicans at the state and federal levels, applies to able-bodied adults without dependents enrolled in Arkansas Works—the state’s version of Medicaid expansion in which Medicaid pays premiums for people to access private health insurance on the health insurance marketplace. The policy today applies to enrollees between the ages of 30 and 49, and will expand to those age 19 to 29 next year. Once fully implemented, the work requirement is expected to apply to more than half of the 265,000 people enrolled in Arkansas Works.

Those subject to the work requirement must report 80 hours of work activity every month, which could include employment, job training, job searching, school, health education classes, or volunteering. Work activity must be reported online. People who fail to meet these requirements for any three months out of the year will lose Arkansas Works coverage until the next calendar year.

State officials say they tried to spread awareness by sending letters to Medicaid recipients’ homes, making phone calls, and creating flyers for community organizations to display. Nine of the 18 people Greene interviewed were subject to the work requirements based on age; of those nine, four reported they had received letters from DHS about the work requirement.

“The reality is this is a difficult group to reach, but when you are trying to make a large change like this where people are going to be cut off from Medicaid, there needs to be a much greater effort,” Greene said. “Better education directly to the Medicaid recipients, which I acknowledge is very hard to do, and better education of people working in social services so people can get the help they need.”

Greene said many of the people she interviewed were overwhelmed by the online reporting mandate. The group reported a mixed level of comfortability with computers. While some recipients she interviewed did have access to the internet and a computer, others did not.

Internet access is a hurdle for the population affected by the Medicaid work requirements, Tritt said. Arkansas has a 17 percent poverty rate, and ranks 48th in the country for internet access, according to BroadbandNow. Thirty percent of the state’s population has access to fewer than two internet providers, and 230,000 Arkansas residents don’t have any wired internet providers where they live.

The policy allows Medicaid recipients to appoint someone else to log their work activity online for them. But that still requires the person appointed to be tech-savvy enough to download the appropriate documents online, Greene said.

The Medicaid recipients Greene spoke to reported other barriers and life circumstances affecting their ability to adhere to the work requirement, especially if the state does not make additional investments in job training, employment supports, and job search assistance.

“The complexity of people’s lives is so profound. Two people talked about recently getting out of jail. One was on the edge of homelessness. People spoke of mental illness. People’s lives were really complicated,” Greene said. “The assumption of personal responsibility that is underlying this policy doesn’t necessarily take into consideration the challenges people are facing on a daily basis.”

Linking Medicaid coverage to work-related activities is a highly contentious public policy. The Obama administration rejected Republican requests for Medicaid work requirements on the basis that such policies do not support the objectives of the Medicaid program. In March 2017, the Trump administration affirmed its support for Medicaid work requirements. By early 2018 it had approved four states’ work requirement proposals: Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky and New Hampshire.

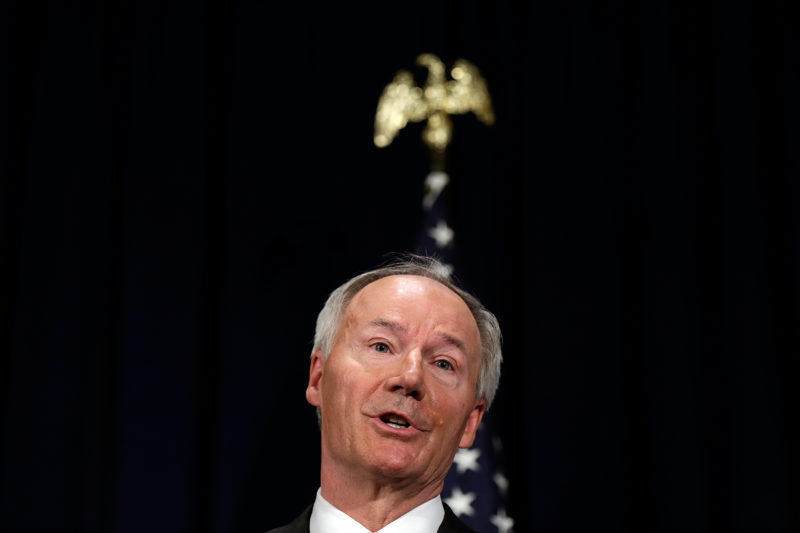

Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R), who is up for re-election in November, has been a proponent of the Medicaid work requirements. His Democratic opponent, Jared Henderson, opposes the Medicaid work requirements, saying on Facebook, “At best, this is stunningly poor policy. At worst, it’s an intentional effort to deprive some of our neediest people of health insurance.”

Arkansas is the only state to lock people out of coverage for noncompliance for up to nine months. In Indiana and New Hampshire, those who lose coverage for failing to comply can have it restored immediately upon coming into compliance.

The policy has not yet been implemented anywhere but Arkansas, and while the Trump administration has approved four states’ requests, Medicaid work requirements are facing legal challenges. A federal judge in Washington, D.C., blocked a similar work requirement in Kentucky from taking effect in July. Lawyers at the National Health Law Program, Legal Aid of Arkansas, and the Southern Poverty Law Center have filed a suit in the same court to stop Arkansas’ requirement, arguing the Trump administration exceeded its authority when it approved the measure.

Not only will this policy affect the thousands of recipients who have lost coverage, but that drop in the state’s insured rate will have an effect on the state’s hospitals, the economy, and public health, Tritt said.

“The ER is not the place for routine care. We want to do in our emergency departments what should be done and when Arkansans have coverage options then they are being seen in the right place at the right time with the appropriate health care provider, and that is what makes everyone healthier,” Tritt said. “Even if those 4,500 patients [who lost coverage] don’t come to the ER they could be putting off much needed care and in turn, when they do receive care, it costs them and the system more. They are not able to maintain health.”