As Providers, We Must Pay Attention to the Social and Systemic Factors Behind Health

Historical, social, and economic issues are absent from medical charts, yet they all have important clinical implications.

Recently, a generous donor supported my clinical practice by ensuring that we had a clinical psychologist who could see my pediatric and adolescent gynecology patients alongside me. This “dual provider” model ensures essential mental health services. For example, providers traditionally scheduled follow-up visits for these types of services. Now, patients no longer have to make a second visit for counseling services and have a connection to another caring provider in one visit.

The model, however, doesn’t fix everything. Each visit requires time away from school, a parent missing work, the cost of transportation, or potential lost wages. These structural factors—jobs, transportation, schools, and the like—can affect health. This is why providers should not treat appointments as simple 15-minute slots on a schedule. We must pay attention to the social and systemic factors that contribute to health, not just the clinical problem.

In 1994, the term “reproductive justice” was coined by a group of Black women, who stated that “any woman’s reproductive destiny is directly linked to the conditions in her community and these conditions are not just a matter of individual choice and access.” Today, the term is still timely amid a climate of growing political uncertainty.

Proponents of reproductive justice aim to address the myriad factors that disempower people and prevent them from exercising reproductive autonomy. These factors—historical, social, and economic in nature—are absent from medical charts, yet have important clinical implications. Underlying social and economic injustice can interfere with the ability to access reproductive care, leading to worse health outcomes.

How can the reproductive justice framework inspire our work as medical providers? As patient advocates, we can use our voices along with our education, influence, and pocketbooks to improve systems that too often perpetuate reproductive health disparities. We can educate our colleagues about issues such as confidentiality for adolescents and safety of contraceptive methods. We can influence leadership at our institutions to push for parking vouchers, efficient clinical visits, and social services at the time of a visit. We can also take patient stories to legislators to help them understand how policy impacts the health and well-being of people, particularly among those most marginalized or vulnerable.

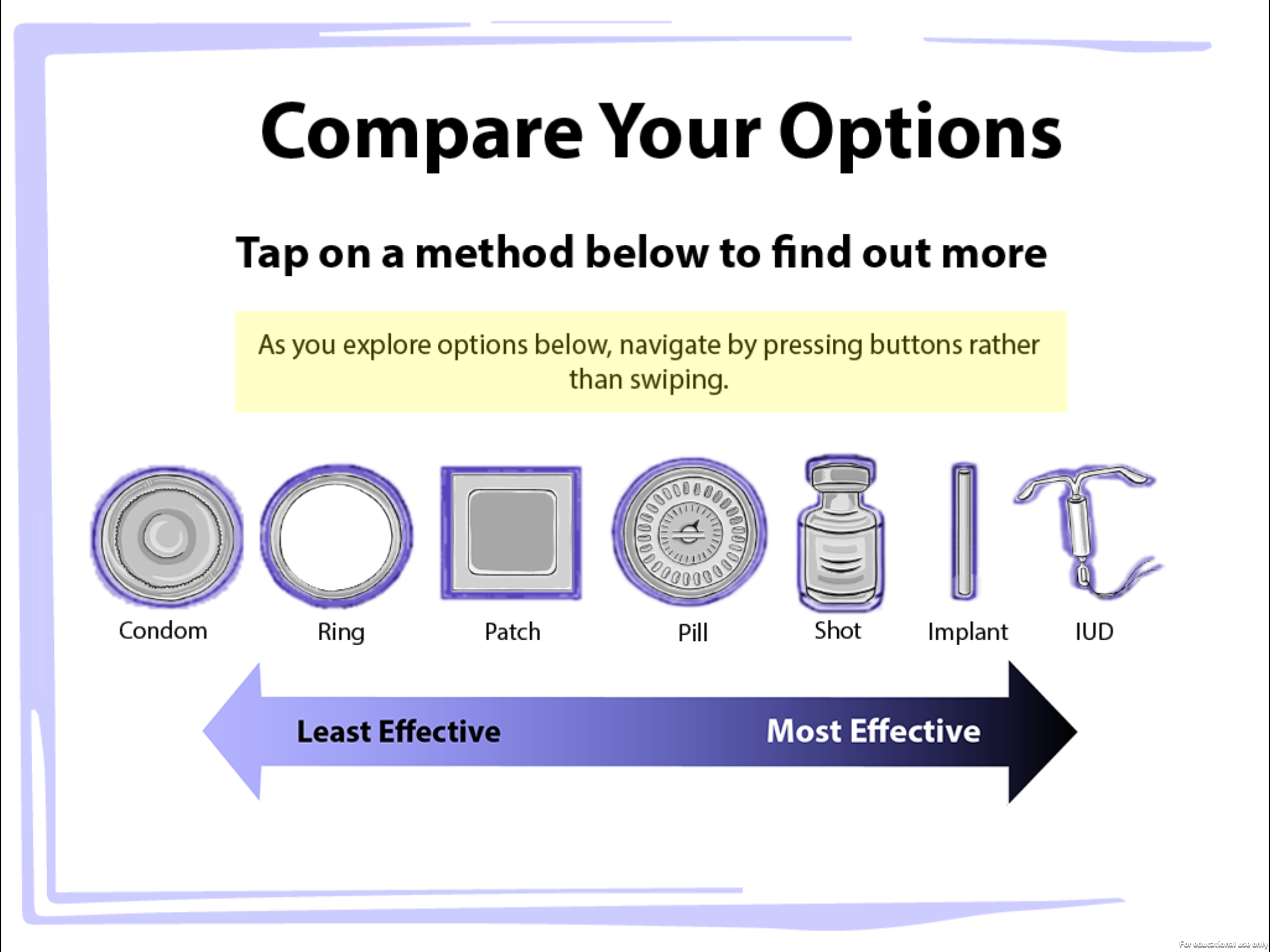

Reproductive justice can also inform our clinical practice. A first step is recognizing the complex set of experiences that each person brings to the office visit. We should value their voices and perspectives and understand patients as the experts of their own lives and health goals. The provider must, therefore, authentically engage patients by honing listening skills and patience, asking questions, and creating the space that allows the patient and provider to arrive at solutions together. For example, an adolescent may value preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) over pregnancy and opt for condoms rather than a more effective method of contraception. To the provider, this choice may seem illogical given the higher failure rate of condoms and the consequences of adolescent pregnancy. Yet, the teenager may be more focused on the prevalence of STIs, the ease of access to condoms, and the consequences of HIV. So, condoms would be the right choice for her, and the clinician must respect that.

Today’s climate of change provides an opportunity to rethink and innovate the clinical visit. My research center at the University of Chicago, the Center of Interdisciplinary Inquiry and Innovation in Sexual and Reproductive Health (Ci3), serves as an example. Our team includes faculty, designers, and researchers who work with young people to design mobile applications and other media interventions. According to one study, adolescents spend nine hours a day using technology, so a mobile app for contraceptive education can be a resourceful tool.

Ci3 has designed three apps: “PreCounselor,” “miPlan,” and “rPlan.” In our clinical trials, young women use these apps in waiting rooms to learn about contraception before their visit, capitalizing on downtime and preparing them to engage with their provider during the upcoming visit. The first app, PreCounselor described all forms of contraception and answered questions that adolescents raised, such as: “Which is most effective at preventing pregnancy?” Or, “What will my partner think?”

Expanding on research that has shown having a provider who looks like you can build trust and rapport, our second app, miPlan, featured videos of young Black and Latinx women who provide peer-to-peer contraceptive advice and counseling to the young women accessing the app. miPlan focused primarily on contraceptive effectiveness and did not emphasize the use of condoms.

Thus, the next iteration of the app is called rPlan, an app that emphasizes dual protection by guiding adolescents to create an individualized strategy to prevent both STIs and pregnancy. This app challenges the paradigm of providers offering long-acting reversible contraception first, in which patients are given information about the clinically proven most-effective methods before discussing other options. rPlan gives full information about all methods of contraception and helps adolescents choose a method based on what they value most.

The larger goal is to change the systems and policies that create disparities in health. As providers, we can practice reproductive justice in each clinical visit. While not everyone will rely on or have access to technology and design, we can all be more curious and creative. By learning about the communities where our patients live, we can better understand and mitigate factors that may impede their overall health and well-being. We can view them as authorities on their own lives and respect their decisions. With these principles and a willingness to challenge dogma, we may call ourselves proponents as well as practitioners of reproductive justice.