A ‘McCarthy-Like Witch Hunt’: Legal Experts Weigh in on Operation Targeting Immigrants for Denaturalization

"I can only assume the Justice Department is proudly publicizing this first denaturalization because we're going to see ramped-up efforts to denaturalize people. I find this very distressing," said one expert.

Read more Rewire.News coverage of Operation Janus here.

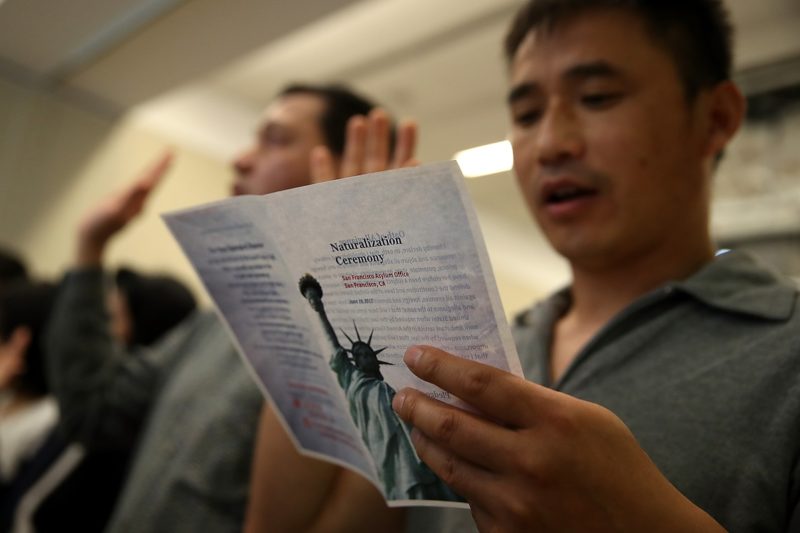

The Tuesday announcement from the Department of Justice (DOJ) that it had secured the first denaturalization as part of Operation Janus was the result of months of work by the Trump administration.

In September, after President Donald Trump took office and laid out his anti-immigrant agenda and plans for mass deportation, the federal government filed three civil denaturalization complaints in federal courts in the Middle District of Florida, District of Connecticut, and District of New Jersey, against Parvez Manzoor Khan, Rashid Mahmood, and Baljinder Singh, respectively. In a press release at the time, the DOJ said that these three South Asian men “allegedly obtained their naturalized U.S. citizenship by fraud.” The DOJ announced on Tuesday that a New Jersey judge had “entered an order” canceling Singh’s naturalization certificate on January 5.

The news confounded many, as the immigration enforcement operation began as a counterterrorism measure ten years ago and had effectively been disbanded in 2016. Advocates and legal experts who spoke to Rewire were perplexed as to why the Justice Department would recycle Operation Janus and proudly trumpet the denaturalization in a press release without any mention of terrorism.

Eric Cohen, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, told Rewire that in his 30 years doing work around immigration law, he had never before encountered a large-scale operation to denaturalize people.

“It’s a gross misjudgment to automatically assume anyone [Operation Janus is] targeting by reopening their case is someone who is has been convicted of a crime or lied about something of substance to get naturalized,” Cohen said. “Right now three are being prosecuted and we don’t know anything about them outside of what the DOJ has told us. That is troubling, and so is the fact that we have no idea how many people this will ultimately impact.”

A closer look at the men recently targeted through Operation Janus reveals a number of similarities.

In September 2017, when the denaturalization complaints were filed in courts, Khan, from Pakistan, was in his 60s and had been a citizen for 11 years. Mahmood, from Pakistan, was in his 40s and had been a citizen for 12 years. Singh, from India, was in his 40s and had been a citizen for 11 years. All three men had been naturalized during the summers of 2005 and 2006 and each man arrived in the United States with questionable paperwork or no paperwork at all. All failed to appear at their immigration hearings, which triggered their deportation orders. Eventually, all three men adjusted their status by marrying U.S. citizens and by using names that were different than those featured on their deportation orders. In response to the news that the DOJ secured the first denaturalization, Muslim Advocates, an Oakland-based national organization, has filed a Freedom of Information Act request “to shed light on why these men have been targeted and why these efforts are even taking place.”

The Trump administration has spared no excuse when it comes to targeting undocumented communities, most often claiming the people targeted are violent “criminal aliens.” The rhetoric may be effective in swaying public opinion, but end-of-year numbers released by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reveal who is really being targeted. They have largely been undocumented immigrants charged with misdemeanors such as DUIs; people taken into custody reportedly in retaliation against so-called sanctuary cities or as part of “silent raids” on those attending their regularly scheduled immigration check-ins; or people simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, picked up as “collateral arrests,” guilty of no more than being in the United States without authorization.

At the same time, the Trump administration also has made major strides in harming immigrant communities in the United States with some form of status. Trump rescinded Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has ended Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for immigrants from several countries.

Despite the Trump administration’s first year of “shock and awe” targeting immigrant communities, the Justice Department’s announcement of a denaturalization was still surprising. But there is a precedent for this sort of thing.

Denaturalization Almost Always “Overtly Political”

Merely having used multiple identities or having a previous final deportation order does not necessarily automatically render a person ineligible for naturalization. Legal experts explained to Rewire this week that a person’s citizenship can be revoked for a wide array of reasons and that denaturalization itself is not uncommon.

Dan Kesselbrenner, executive director of the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild, told Rewire that the most widely known instances of denaturalization are almost always “overtly political.”

For example, John Demjanjuk was infamously denaturalized in 1981 after being identified by Holocaust survivors as “Ivan the Terrible,” a concentration camp guard who assisted in the murder of 28,060 Jewish people. More recently, the highly polarizing U.S. Supreme Court case of Divna Maslenjak, a refugee from the former Yugoslavia, forced the Court to grapple with complicated questions related to false statements made during the naturalization process—primarily, whether or not lies made during the naturalization process can strip someone of their citizenship even if the information was not material to deciding whether to grant citizenship. (Maslenjak lied about her husband’s whereabouts during the Bosnian Civil War, in which he served in a military unit responsible for the 1995 massacre of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims.) Rasmea Odeh was denaturalized and deported last year for failing to disclose her conviction in 1970 for bombings in Jerusalem.

“It is a crime to obtain naturalization in fraudulent ways. By that I mean, for example, someone failed to mention they’d been convicted of a crime during their naturalization process. In that case, their citizenship can be revoked,” Kesselbrenner said. “But you can also be denaturalized if there was a mistake made by USCIS that had nothing to do with you or if you made a mistake by omitting something in your application you didn’t realize you had to include. That’s where all of this gets tricky.”

Earlier this month, Judge Stanley R. Chesler of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey issued the first denaturalization under Operation Janus, almost ten years after the enforcement operation first launched and over a year since the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) declared it “disbanded.”

Baljinder Singh, also known as Davinder Singh, allegedly arrived at San Francisco International Airport on September 25, 1991, without travel documents or proof of identity, claiming his name was “Davinder Singh.” Singh was placed in exclusion proceedings, but did not appear for his immigration court hearing and was ordered deported on January 7, 1992. On February 6, 1992, he filed an asylum application under the name “Baljinder Singh,” according to the DOJ, and “claimed to be an Indian who entered the United States without inspection.” Singh abandoned his asylum application after he married a U.S. citizen, who filed a visa petition on his behalf. He was naturalized under the name “Baljinder Singh” on July 28, 2006.

According to court documents, Singh did not oppose the motion for denaturalization and did not respond to the original complaint filed against him in September. Judge Chesler ruled that Singh’s citizenship orders and certificates of naturalization were “illegally procured or were procured by concealment of a material fact or by willful misrepresentation.”

Based on the information publicly available from the Justice Department, Singh had no criminal record, and it wasn’t criminal activity that put him on the radar of immigration authorities. It’s also unclear if there were reasons Singh felt compelled to use a different name and if he feared persecution in his county of origin. There is also no way to know if his 1992 asylum claim was valid.

“Just reading over the information provided by the Justice Department, his actions are consistent with someone who is afraid and who had a history that they didn’t reveal,” Kesselbrenner said. “I want to make it very clear that there is no way the Justice Department wouldn’t have outlined his criminal conviction, if he had one. He likely didn’t even have any immigration violations because if he had, it would have been difficult for his spouse to petition for him successfully. Really all we know for sure is that for whatever reason, he gave a different name and didn’t mention his previous deportation order and that made it easier for him to get his green card. This is a minimal violation and the details indicate this is someone who was afraid and wanted to come to the U.S. to escape persecution or be with his family. I find [his denaturalization] very alarming.”

Many are now concerned that denaturalization will become a trend under the Trump administration.

“This is like shooting a bomb to get a mouse instead of just using a mousetrap. It’s overkill; it’s disproportionate. This person didn’t answer questions properly and the response is disproportionate to the offense. I’m alarmed. It’s excessive enforcement and it illustrates the administration’s bias and its distorted priorities,” Kesselbrenner said.

Impetus for Denaturalization Operation

“Operation Targeting Groups of Inadmissible Subjects,” the original enforcement operation that would eventually become Operation Janus, first emerged as a counterterrorism measure. The operation dates back to 2008 when a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) employee identified 206 people who had received final deportation orders, but used a different name or date of birth to obtain legal permanent residency or citizenship, according to a September 2016 report from DHS OIG. What stood out about these 206 is that they came from “special interest countries” or a country that shared a border with a special interest country. DHS OIG defines a special interest country as “countries that are of concern to the national security of the United States.”

In 2009, CBP handed the research pertaining to the 206 individuals over to DHS and the enforcement operation morphed into what is now officially known as Operation Janus. Armed with this research, the DHS Counterterrorism Working Group coordinated with other agencies under DHS to target people from special interest countries who had received immigration benefits like naturalization, despite having final deportation orders. In 2010, DHS’ Office of Operations Coordination (OPS) began forming what would become the Operation Janus working group.

There was seemingly no movement on the operation until July 2014, when OPS provided OIG with a list of 1,029 names for those who came “from special interest countries or neighboring countries with high rates of immigration fraud, had final deportation orders under another identity, and had become naturalized U.S. citizens,” according to the DHS OIG report. Of those 1,029 people, 858 did not have digital fingerprint records in the DHS fingerprint repository at the time USCIS was reviewing their citizenship applications.

The missing fingerprints say nothing about the intentions of the 858 people identified by the federal agencies as having improperly obtained status in the United States. DHS and Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), the country’s previous, sole immigration agency that DHS absorbed when it was formed in 2002, failed to digitize and upload all old fingerprint records into the repository.

News outlets like the New York Times have long referred to INS as a “beleaguered immigration agency” because of its many failures to keep proper records and follow its own protocols for naturalization. The Clinton administration moved to denaturalize nearly 5,000 people after INS, looking to streamline the naturalization process of over 1 million people, granted citizenship to those people who were alleged to have had a criminal arrest or lied about a criminal history, both of which would have disqualified them from naturalization. The agency made so many mistakes that it had to adopt a simpler revocation process, no longer requiring each case to go before a federal court judge. Under the INS system, an immigration administrative officer would decide a revocation case and a defendant could appeal the decision to a federal judge. This process no longer stands; going to a federal judge is required to strip an immigrant of their citizenship.

“Denaturalization is a hard process, as it should be. These are U.S. citizens with constitutional protections. They have to go to a federal district judge to decide if evidence shows that this person received naturalization improperly,” Cohen said.

“A McCarthy-Like Witch Hunt”

Little is publicly known about the hundreds of thousands of naturalized immigrants whose citizenship the DOJ suspects is dubious due to missing fingerprint records. DHS OIG explained that while their fingerprints may not have been available when they were naturalized, their digital records are now available to federal officers, as are their immigration histories. According to DHS OIG, some identified under Operation Janus were law enforcement officials and people who had obtained security clearances to work in sensitive positions. Two even had aviation workers’ credentials, allowing them access to secure areas of commercial airports.

Those are extreme examples. For the most part, a bulk of the individuals identified as part of Operation Janus have not been investigated and denaturalized, giving the Trump administration a large pool to draw from.

There is another concern: Once an immigrant has been naturalized, they have the right to petition for family members in their countries of origin to come to the United States. If, Singh, for example, had successfully petitioned for a loved one to migrate to the United States and naturalize, their citizenship may now be revoked. It is unknown if Singh did indeed petition for others, but it would be an effective strategy as part of a vehemently anti-immigrant administration. Trump has repeatedly said he wants to end “chain migration.”

Kesselbrenner said it may have taken eight years for Operation Janus to secure its first denaturalization because while it was an Obama-era program, U.S. attorneys in the administration likely didn’t think it was worth pursuing, especially because nothing suggests that the naturalized citizens in question misled officials for nefarious reasons.

“Just read through the Sessions memo about wanting to prioritize non-citizen offenders. Under this administration, I don’t think it’s a stretch to think they don’t really view naturalized immigrants as American citizens,” Kesselbrenner said. “My best guess is that because the Trump administration is so concerned with enforcement in immigrant communities, they’ve chosen to prioritize this operation in ways another administration wouldn’t. It’s one thing to target these people and convict them for hiding serious criminal backgrounds. It’s an entirely different thing to go after people who’ve been citizens a long time because they were dishonest for reasons we don’t even know. It’s a waste of resources. It’s vindictive. It’s a waste of taxpayer money and it’s totally unreasonable.”

Also alarming to the people who spoke with Rewire is USCIS’ collaboration with the Justice Department on Operation Janus. USCIS is often considered the “services arm” of federal immigration agencies operating under DHS, one that does not participate in enforcement.

In a statement provided to Rewire by a USCIS spokesperson, the agency said that its participation in Operation Janus is part of its mission “to combat fraud that poses a systemic risk to the integrity of our nation’s immigration system.” The agency also asserted that some identified by Operation Janus “may have sought to circumvent a criminal record,” though as Kesselbrenner noted, it’s an odd move not to highlight one of these instances in the first three complaints filed for denaturalization. The federal immigration agency also said it could not provide additional details regarding the techniques and processes it used to identify and handle the cases, or any information regarding the length of investigations.

After securing the denaturalization against Singh, USCIS Director Francis L. Cissna said in a statement, “This case, and those to follow, send a loud message that attempting to fraudulently obtain U.S. citizenship will not be tolerated. Our nation’s citizens deserve nothing less.”

Cohen said that the framing of this as a protection of citizenship is “frightening” because to the executive director, it reads more as an attack on citizenship. There’s also the fact that the resources being funneled into denaturalizing people could just as easily be funneled into addressing the naturalization backlog that has seen wait times nearly double since 2016.

“Obtaining citizenship is the most important right and privilege that people have. To go after people who have been citizens for years—and for what seems like very insignificant reasons—is a McCarthy-like witch hunt that doesn’t express the administration values citizenship; it expresses that they’re prioritizing xenophobia,” Cohen said. “An administration that is xenophobic and anti-immigrant, as this one is, will have an increased perception of fraud in the immigration system. This is incredibly politicized and I can only assume the Justice Department is proudly publicizing this first denaturalization because we’re going to see ramped-up efforts to denaturalize people. I find this very distressing.”