The CDC’s Language Ban Is More Than an Attack on Words—It’s an Attack on Basic Public Health Values

We as biomedical and public health professionals are tasked with a responsibility to understand and promote good health for everyone in the United States; it is time for our elected and appointed officials to do the same.

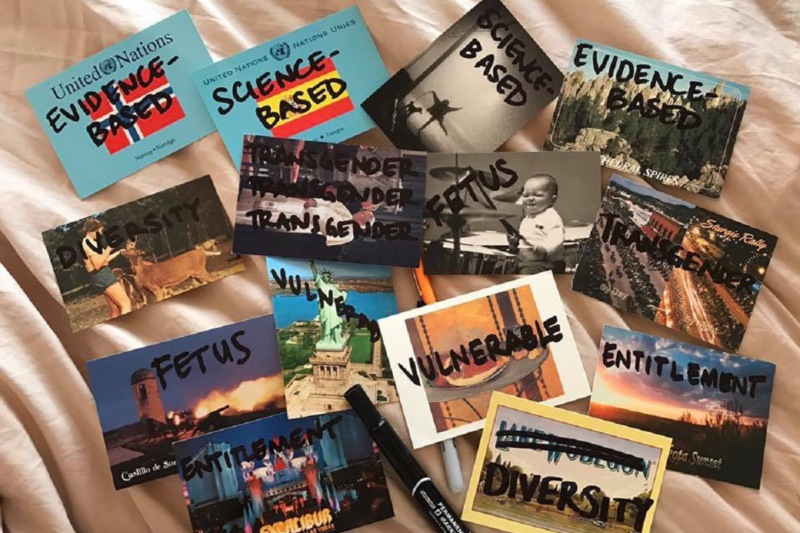

Last Friday, the Washington Post reported that senior members of the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) counseled analysts to avoid using seven words in future budget and supporting documents that would be disseminated to CDC partners and to Congress: “evidence-based,” “science-based,” “vulnerable,” “entitlement,” “diversity,” “transgender,” and “fetus.”

Two days later, CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald and a spokesperson from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—which oversees the CDC—both argued that no bans on words existed and that the entire story was a “mischaracterization of discussions regarding the budget formulation process.”

Despite the seeming about-face from both the HHS and CDC, the concern among the medical and public health community still remains: What are the implications for banning (at worst) or deeming unseemly (at best) words in budget discussions about the public health of our nation, and what does this mean for the future of public health in the United States?

It is somewhat typical to see a shift toward and away from euphemisms related to abortion and LGBTQ health depending on the party in office. But the reported “ban” goes beyond such changes. Rather, it is a fundamental attack on the professional values and practices that make up public health and the scientific process in general. Public health and biomedical professionals need to be the ones to define and uphold our professional values and practices. We need to be the ones to define what our core government institutions should be doing with regard to health research and medical care, and how these two tasks should be enacted. Both the presence and the specific contents of a language ban are a fundamental shift away from this approach to government public health. Alongside our institutions and our leaders in schools of public health and medicine, we need to stand up now and make sure that our government health agencies can continue to function according to the core values and skills of our mutual professions.

Basic public health values include basing decisions on the best available scientific evidence and the need to protect the most vulnerable. Whether considering diverse populations from a racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, sex/gender, or another perspective, it is important to note that the health of any population is a fundamental moral and ethical responsibility of a governmental institution charged with protecting our country’s residents from “health, safety, and security threats.” By not being able to document or consider how public health policies or programs either protect or do not protect vulnerable populations—such as immunocompromised people in relation to vaccination—or particularly affect different populations—such as policies punishing Black women more than white women for drug use during pregnancy, and thereby contributing to divergent possibilities for receiving support—public health agencies risk doing more harm than good. This commitment is not, as conservative pundits would have us believe, an instance of “political correctness.” Rather, it goes to the very purpose of the CDC itself: to protect people and to keep them healthy and safe.

Consideration of the word “fetus” bears further scrutiny. In 2017, the mention of the word “fetus” immediately brings to mind the Zika epidemic, which has known effects on fetal development and long-standing adverse neurological outcomes in children. By curtailing the use of the word in CDC budgetary documents, a concern remains: the possibility of enacting an overt pro-birth agenda, which devalues a scientific approach to pregnancy-related issues by indirectly promoting a woman’s duty to gestate. How? If one cannot investigate the problems in fetal development, then scientific data on issues like Zika will be “unavailable” to offer an accurate clinical prognosis. Therefore, issues like fetal malformations and birth defects—diagnoses that could trigger a discussion of abortion—are more likely to be shrouded in scientific mystery. Shrouding these issues in scientific mystery also makes it less likely for public health agencies or clinicians to provide accurate information to inform women’s decisions about whether to continue a pregnancy or have an abortion.

Public health professional skills certainly include navigating the challenges when evidence and the preferences of the group of people affected by the public health decision are not in alignment. And, while public health policy may sometimes end up prioritizing preferences of people affected over evidence, the role of public health professionals and government agencies is to competently assess and accurately communicate what the best available research evidence and science says. In the same way that physicians and nurses provide patients with information based on the best available evidence and science, and then work with them if the patients want to do something else, government public health practices also work through careful negotiation. However, the choreography between policymakers and public health professionals does not change the primary goal of bringing the best available evidence and science to the conversation.

To be sure, part of the skill of a government public health professional is to recognize the political constraints on what you can and cannot do. It is to be expected that administration changes will involve development of and use of different euphemisms and shifting funding to different political priorities. Public health professionals in government need to be able to weather these shifts. However, when political priorities of an administration prohibit those working in government from doing their jobs in ways that are consistent with professional values and training, it is time for public health, medical, and nursing professionals to draw a hard line.

Public health professionals should not stand for this fundamental attack on scientific methodology in our most important government public health institution. We call upon members of the HHS and the CDC to both denounce such obvious manipulations of language while emphasizing transparency around budgetary policy and funding opportunities as they relate to public health and biomedical research and practice. Especially in our current political climate, physicians, nurses, public health leaders, and others engaged in preserving the health of our country will not stand idly by, nor will we stop critically evaluating data coming from the highest levels of government. We as biomedical and public health professionals are tasked with a responsibility to understand and promote good health for everyone in the United States; it is time for our elected and appointed officials to do the same.