Why Aren’t More Trans Women on PrEP?

“So much of the research and the way trans health-care programs are designed is not trans-affirming or developed by trans folks.”

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

Feelings of forced vulnerability and exploitation cycled through my body as I waited for my number to be called at a local HIV testing clinic. I didn’t know what to think of my predicament. I was the girl who always doubled and tripled down on safer sex. I was always the one asking my partners the hard questions about potential sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and condoms and their sexual practices. This time was different.

After my line of questioning and finding out my partner didn’t have any condoms, we continued to make out barely clothed. I thought nothing of it. This was someone I had been dating for a few months, so he wasn’t a stranger and I wasn’t worried about being in such a compromised position. I trusted he wouldn’t take things too far, but I was wrong.

He decided our usual rules didn’t matter, and he forced a quick moment of condomless penetration. My eyes opened wide and I pushed him back with force. I drilled him about details on the last time he had been tested. It had been a while since I asked. When we’d first met, he assured me he got tested regularly every three months—but suddenly the time frame grew to “about six months.” I realized this whole thing had been a horrible lapse in judgment.

I felt taken advantage of. And I couldn’t help but think about one major statistic as I came to grips with what had happened: Trans women are 49 times more likely to contract HIV than the general population, according to one global meta-analysis of research. Of course, the numbers are even higher for trans women of color. Knowing this, I wondered how this scare could have happened. How could I have let him do this to me? And what could I do to ensure this never happened again?

Once positioned across from a nurse at the clinic, I fumbled my fingers. I’m not the religious type, but I even prayed a bit. The nurse pricked my finger, and we sat and waited for the results to appear in the rapid test.

Negative.

In a time where the definition of consent is constantly debated and stealthing (or non-consensual condom removal) is described as a trend, I struggle with a constant fear of being taken advantage of. Being a receptive partner who is more at risk for STI contraction and a woman who often dates cisgender heterosexual men means I’ll always be opening myself up to even more risk. I knew what I needed to do to calm the storm inside me, so I asked my primary care provider about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

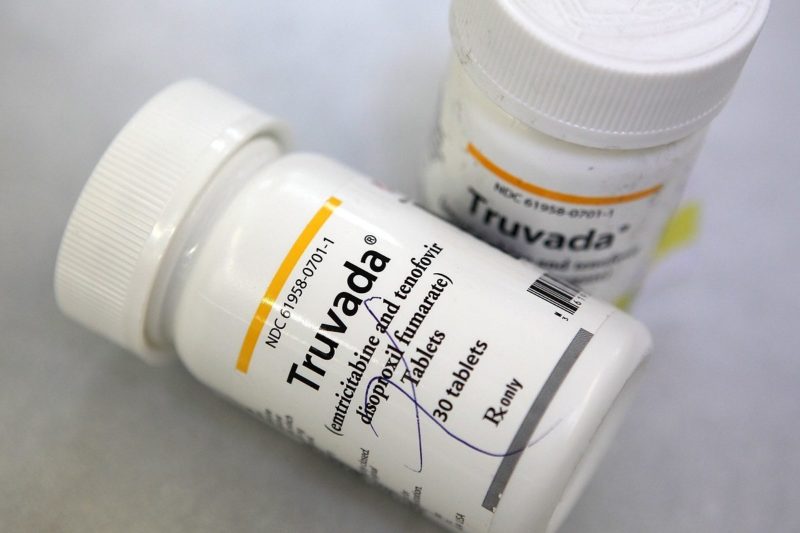

PrEP, also known by its prescription name Truvada, is a medication that can be taken to reduce the risk of contracting HIV-1 infection, the most common of the two main types of the human immunodeficiency virus. People begin taking PrEP for a variety of reasons—if they have consistent casual sex, a partner who is living with HIV, or simply want to have condomless sex.

“I think [PrEP is] a great option for folks. It adds to the array of choices that we now have regarding HIV prevention,” said Carlo Hojilla, a nurse at the Kaiser Permanente Multi-Speciality Transitions Clinic in Oakland, California. “Sometimes condoms work well for folks and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes you just want that extra layer of protection … It’s about figuring what works best for a person depending on their health.”

I first heard about PrEP in a workshop led by Black cisgender queer men, so even at the onset the messaging wasn’t tailored to my experience as a Black transgender woman. In fact, none of my primary care providers or the nurses or sexual health navigators I’ve encountered over the years have ever said anything to me about PrEP or detailed information about safer sex methods to me.

“Providers don’t talk to trans people about sex. They may ask the type of sex [you] have or assume [types of] partners, but they don’t ask if people have sex with other trans folks. I think it’s necessary for people to rethink how we have conversations about sex,” said Gus Klein, a trans health researcher at Hunter College in New York City. “We also need to rethink things and understand that a woman could have a penis and a man could have a vagina instead of saying our defining characteristics are our genitals.”

The needs of trans people are regularly neglected in the health-care industry; sexual health is no different. In Injustice at Every Turn, a 2011 report on national transgender discrimination, 50 percent of respondents reported having to teach their health-care providers about transgender care.

I was wary of my provider’s reassurance of PrEP’s effectiveness in our initial discussion. I knew most of the research out there centered on men who have sex with men (MSM), and I was particularly worried about whether PrEP would negatively affect my medical transition. Hormone replacement therapy can greatly affect the body, as documented in the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standards of Care, so it’s important to closely monitor how new medications can affect an existing regimen.

“I think the main thing to [do when considering PrEP] is talking to a provider about it. They’ll run some tests and check your kidney and liver and see if you’re a good fit for it. You need to know what it entails,” Hojilla said. “For it to work for you, it needs to be taken every day. [You should] think about how it fits into your life and everyday activities.”

A major element of taking PrEP is consistency. For trans women who are on hormone replacement therapy, sticking to a schedule for hormone replacement therapy is key. In theory, this routine should be conducive to adding PrEP, which involves regular HIV testing every three months and taking the pill once a day. There are common reported side effects, but typically they subside within the first week.

“I was feeling nauseous [when I started PrEP] and having really bad headaches. I don’t know if it was the combination of taking hormones and PrEP,” said Shakyara Ralat, 30, a trans woman of color who works at a HIV prevention clinic in Orlando, Florida. “The second week, I was better. Then, I was fine after that. I just take [the pill] in the morning now and go.”

The first week I took PrEP my experience was very similar to Ralat’s. Everything I ate tasted weird and I had nausea for about three days, but after that I was fine. Like Ralat, the initial side effects didn’t deter me from moving forward with the medication.

“I don’t understand why everybody isn’t on it. I would say it’s for everybody. It’s a way to stay healthy. I don’t see why we should keep anybody from having that option,” she said. “I don’t have to second-guess myself when I engage in sexual activity. I don’t have to worry about the condom breaking or being exposed to HIV.”

Ralat believes doctors don’t discuss PrEP with trans women more often because many think having such a powerful method of prevention will encourage promiscuity. Further, to many providers, HIV and AIDS are still largely seen as a “gay man’s” problem, and transgender health discourse is often only discussed in relation to medical transition.

“People think all we need is hormones. I think PrEP starts to open up a larger conversation. Because HIV rates are so high, this should be something we offer to people and let them have a choice in the matter,” said Klein. “So much of the research and the way trans health-care programs are designed is not trans-affirming or developed by trans folks.”

He also said there’s only been one clinical trial called iPrEx (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiative) that included 19 trans women. A follow-up analysis completed at the University of California, San Francisco, included 339 people, but trans women were not listed as participants, though some “reported one or more characteristics associated with transgender women.” That is, some of the respondents identified openly as something other than a transgender woman, but were on feminizing hormone replacement therapy. Language and identity is a complex issue, and this demonstrates how important it is to have trans people involved in how this research is compiled.

Klein also noted that a PrEP public awareness campaign in New York City didn’t necessarily speak to people outside of the MSM category. His research shows that this instance isn’t unique and that trans women are largely unrepresented in the marketing of PrEP or general health-care provider education. Hojilla agreed.

“There are a lot of folks saying, and rightly so, that PrEP has been targeted at gay men or men who have sex with men and trans women as a population have not,” Hojilla said. “I think there are major things we need to work on in terms of messaging to the trans community about PrEP as an option.”

PrEP has proven to be a viable and promising option for gay men to combat the risk of HIV infection. The iPrEx study showed that 44 percent of respondents who actually used the pills consistently had a reduction in risk. It’s time for medical professionals to start prioritizing higher risk populations like transgender women on the target list, especially as treatment options are slated to expand.

“It’s exciting to think of a future where there are even more possibilities [for] prevention. Right now we have the pill for PrEP, but we have things coming down the pipeline as far as injections, Depo shots, implants, rings, and gels,” said Hojilla. “I think we’ll shift our mindset for the better in terms of how we view sex and HIV and being more sex positive and reducing stigma around HIV.”

With more studies slated for release, I hope more transgender women will be more informed of their options and have the choice to minimize their risks should they be placed into a situation outside of their control like the one was in. Transgender women have so much to worry about; scraping together information on our health is the last thing we need to deal with. Researchers and providers like Klein and Hojilla, who are well-versed in transgender HIV prevention, should be the rule—not the exception.

“The diversity of trans women needs to be recognized. We need trans-specific information that talks to the realities of people’s lives, their sexual relationships, and their romantic relationships,” said Klein. “For too long, the conversations about what trans women are doing has come from everyone else. I think it’s resistance when people stand up and say this is what I need and this is what I want.“