Despite Arrests, People With Disabilities Continue to Fight for Their Lives

"This issue is just too critically important for my own independence and that of my children so I felt like it was time to do more," Carrie Ann Lucas told Rewire.

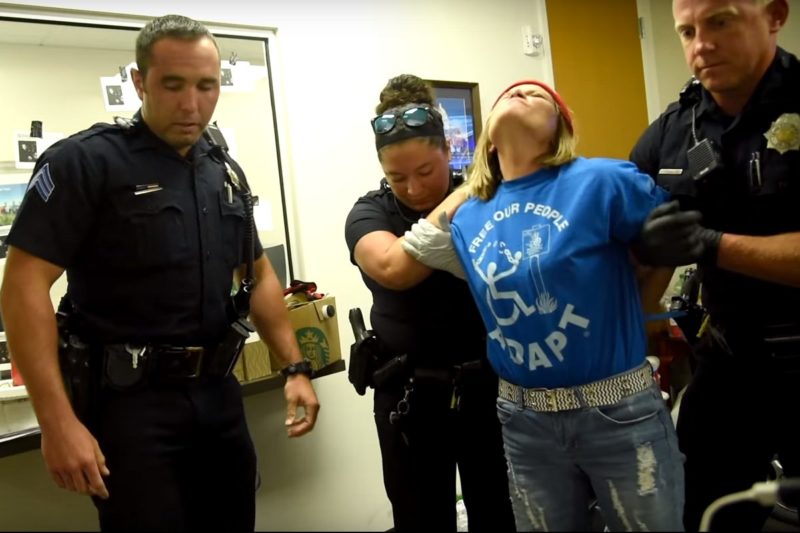

Last week, ten protesters, most of whom have disabilities, were arrested in Denver, Colorado, after holding a “sit in” against the Senate’s proposed health-care bill that lasted three days and two nights—nearly 60 hours—inside the office of Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO). At the request of Gardner’s office, police eventually ordered the demonstrators to leave. Using Facebook, the protesters live-streamed their own arrests, while chanting, “Rather go to jail than to die without Medicaid!” After most of them spent nearly 30 hours in custody, the demonstrators were released from the Denver County Jail.

Carrie Ann Lucas, an attorney who works for the state of Colorado, was the last protester to be arrested. Like all of the protesters, Lucas was cited with trespassing and will need to appear in court later this month. In addition, Lucas—who was taken to a nearby hospital before her release rather than to jail—was charged with interference with a police officer because she refused to tell the arresting officers how to use her power wheelchair.

“I don’t have an affirmative obligation to tell them how to arrest me,” Lucas told Rewire.

Denver police told Rewire that it will not talk about open and ongoing cases and did not answer queries about what arrestees are mandated to tell officers. The Denver Sheriff’s Department directed Rewire to its statement on Facebook.

Lucas is concerned that under the Senate’s proposed bill, she and her children, who also have disabilities, will lose the long-term services paid for by Medicaid that allow them all to live in the community. She told Rewire that before this protest, she had stopped engaging in civil disobedience once she received her law license nearly 20 years ago. But for months, she said, she has been calling, faxing, and emailing Gardner’s office with no response.

“This issue is just too critically important for my own independence and that of my children so I felt like it was time to do more,” Lucas told Rewire.

The protests in Denver were one of many that took place in the days since the Senate GOP released its new health care bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BRCA). In fact, on the day it was released, members of the disability rights group ADAPT—which has been organizing the bulk of the actions—staged a “die in” inside of Sen. Mitch McConnell’s (R-KY) Washington, D.C. office, which resulted in the arrest of 43 individuals, most of whom have disabilities. For people with disabilities, arrest is a necessary risk. The GOP health-care bill doesn’t just imperil their independence; it puts their lives in danger.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the proposed health-care bill would cut Medicaid funding by nearly $800 billion and lead to 22 million more individuals being uninsured over the next ten years as compared to the Affordable Care Act; by 2036, the CBO estimates, Medicaid spending would be reduced by 35 percent. The Center for American Progress estimates that loss of health insurance could result in the death of as many as 27,700 individuals by 2026. More than 10 million people with disabilities, both children and adults, are Medicaid beneficiaries. Indeed, the New York Times recently estimated that 30 percent of all adults with disabilities and 60 percent of all children with disabilities are enrolled in Medicaid.

Notably, as I previously wrote for Rewire, Medicaid is the only health insurance program that funds home- and community-based services that allow people with disabilities to remain living in their community rather than nursing homes or institutions. One such program is personal care assistants (PCAs), which provide in-home care that enables people with disabilities to live independently. PCAs can also help families care for children with disabilities. Although such services are tremendously important to people with disabilities, they are considered optional, meaning states are not required by federal Medicaid law to provide them. Other so-called optional services include dentistry, podiatry, physical and occupational therapy, and coverage for eyeglasses. If states receive less federal Medicaid funding, they will likely only be able to fund mandatory services, and even those will probably be reduced.

Drastic cuts to home- and community-based services will result in the increased institutionalization of people with disabilities. You see, while home- and community-based services are deemed optional, institutionalization and nursing home care is considered mandatory. This should worry Republicans who claim to prioritize savings because longstanding research has found that it is far more cost-effective to provide in-home care and supports to people with disabilities than institutionalizing them.

Moreover, some members of the disability community will be disproportionately affected if Republican health-care reform passes. Vilissa Thompson, a social worker, disability consultant, and writer from South Carolina, pointed out to Rewire: “Individuals who are multiply marginalized will be dramatically affected by Medicaid cuts. This is particularly so for disabled people of color, who already endure medicalized racism and ableism.”

“Without Medicaid, many of us would not have access to the life-saving services and supports we rely on,” Thompson continued. For example, Medicaid funds durable medical equipment, such as wheelchairs and ventilators, which private health insurance generally doesn’t cover. “The lives of disabled people of color are weighing in the balance of politicians who fail to see us as human or as their equal.”

For many people with disabilities, including those organizing protests, the risk of ending up warehoused in institutions or nursing homes if home- and community-based services are eliminated is worth putting their bodies on the line.

Bruce Darling, a national organizer of ADAPT, told Rewire that despite dozens of arrests, the protests will endure. For ADAPT, he says, the Senate recess provides the perfect opportunity for disability activists to target the local offices of senators as well as Republican committee offices around the country.

Darling says that an ADAPT protest at the office of Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) “was a great success in securing her commitment to vote no on any bill that cuts Medicaid.” Collins tweeted last week that she would vote “no” on any motion to proceed.

But Darling told Rewire that the actions have also had less obvious achievements. “I think the protests—covered by the mainstream media for the first time—have shown people with disabilities and others around the country that there is an activist component to our movement. This has opened the door for many to join the fight. It’s been exciting to see that happen.”

Thompson notes, however, that the vast majority of the coverage of the Medicaid debates has involved stories of white people with disabilities. She pointed out, “Allowing the voices, faces, and stories of individuals and communities that will be hardest hit by the cuts is crucial, so that a clearer image of the damaging effects will be widely known.” To effectively oppose the GOP Senate health-care bill, she says, it is imperative that people from diverse backgrounds are invited to be part of the resistance, and that their stories are told.

Of course, that resistance can go beyond protests. Thompson told Rewire, “One way I have engaged in the Medicaid discussion is by writing about what Medicaid means to me as someone who is physically disabled. I shared how my medical care and school experience would have been vastly different if I did not receive essential resources growing up and in my adulthood years. Medicaid is literally the lifeline for myself and our community.”

The disability community’s mobilization to oppose the Senate GOP health care bill and proposed cuts to Medicaid may have far-reaching implications. Indeed, one in five people in the United States—including low-income children and adults, seniors, and people with disabilities—are insured by Medicaid. In other words, people with disabilities are fighting not only for their lives but for the lives of millions of Americans.

As Thompson told Rewire, “Health care is a human right, and fighting for this right is demanding that our humanity is seen and respected.”

She continued, “Health care should not be treated or viewed as a luxury; it is a necessity for living independently.”