Artist at Work: Micah Bazant, Collaborative Designer and Illustrator

Once alienated by the art world's emphasis on individualism, Bazant makes a point of producing portraits and art for, with, and about marginalized people and communities.

This is the third part of an “Artists at Work” series, featuring individuals who are working to shift culture through art. This series is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

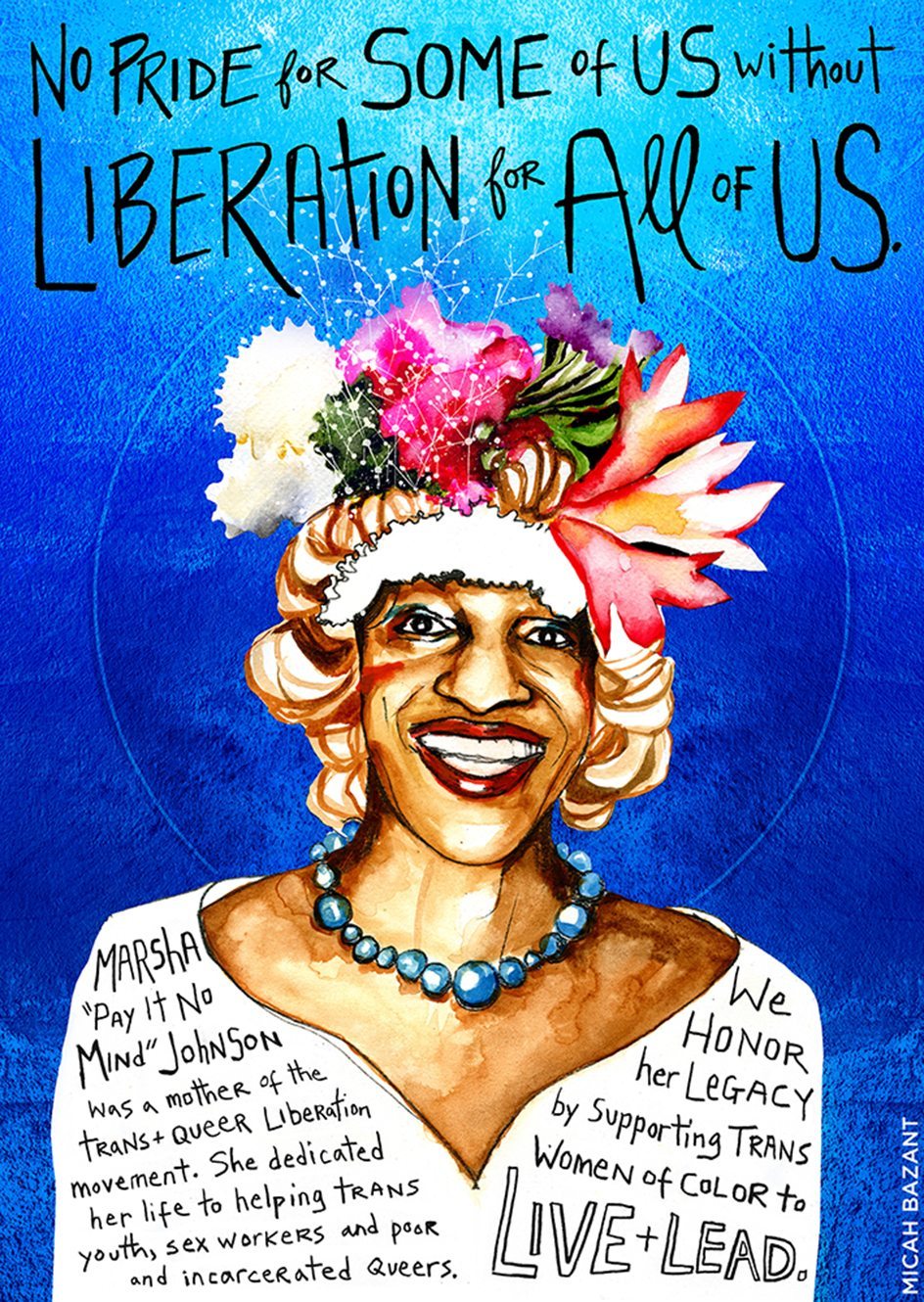

Graphic designer and illustrator Micah Bazant is an “artivist” whose work goes beyond political propaganda. Using vibrant colors and bold statements about social justice, the Bay Area resident creates posters, T-shirts, and digital postcards featuring real and imagined people, ancestors such as Stonewall veteran-activist Marsha P. Johnson and today’s living legends.

Each illustration tells a story honoring and centering communities that are consistently marginalized, namely Black and brown people and queer and trans folks. And those stories are told with the full consent and creative collaboration of those affected by system of oppressions; the resulting art has often been sold to aid its subjects and co-creators, contributing to funeral expenses, costs of living, or bail. For example, Bazant’s work supported community organizing efforts for Arizona’s Monica Jones, a Black trans woman and activist who was profiled and falsely arrested for prostitution, and it raised awareness about the larger issues of profiling sex workers and trans women.

Bazant now works as the inaugural artist-in-residence at Oakland-based reproductive justice organization Forward Together. That professional relationship began with a freelance job updating a brochure and moved to Bazant’s becoming the art director for the annual Mamas Day campaign, which centers parents often overlooked by mainstream Mother’s Day efforts. Now Bazant holds the position full time, an unusual job in the nonprofit sector. Not only do they make and share their original art, they also are co-creating space for artists of color to do their own work.

But even as Bazant is paving the way with their art, including as co-founder of the Trans Life and Liberation arts series, they were once disenchanted with the “art world.” A graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, Bazant found traditional art spaces to be alienating, consumed by the interest in individualism, and not in alignment with their community-oriented values. They soon found themselves working in nonprofits doing administrative and temp work and later doing graphic design for organizations.

Bazant and I chatted via Skype and talked about how they’re navigating being an artist-activist. The edited interview below includes conversations from late 2016 and June 2017.

Rewire: What is your definition of an artist-activist—or what people call an artivist?

Micah Bazant: An artivist is someone who is allowing art and social change to flow through them from the universe to create new worlds.

Rewire: Would that make every artist an artivist?

MB: No, and good question. The “and” is important there. More specifically, I’m interested in the very deep, radical, at-the-roots intersections between art and social change. Many times, art is treated like an accessory to organizing. A nonprofit will commission an illustration for their banner or, conversely, an artist will show at a gallery, skinning the veneer off community organizing efforts or show a surface-level connection to social change.

I’m interested in the deeper relationships and how [artists, organizers, and social change agents] can reimagine what art-making and social change can do to benefit our collective well-being.

Rewire: What values and principles guide your work?

MB: Building relationships and redistributing wealth of all kinds are key goals of my work. My big projects often are in solidarity with communities I’m not directly a part of. For example, the Trans Life and Liberation art series is focused on collaborations with trans people of color. There has been such deep plunder from trans communities of color by mainstream society, by artists, and by white trans people like me. It would be gross for me to be making money off of that project. I have a lot of race and class privilege, which allows me to do this work. Because I am a white artist, I receive more money, resources, and social capital for my art. So a big part of my work is figuring out how my art practice is part of redistributing that wealth.

I try to always be aware of privilege throughout the entire process from the idea creation to how it’s being distributed. Who needs to be coming up with this idea? Who do I need to be in conversation with? Who gets to give feedback on the process? Who is sharing it? How is it being shared? What language is used? Who reviews that language? Are we making prints? Is it being sold? Where is that money going?

It’s not enough to say, “I’m an artist, and everything I create is pure because it comes out of my head uncensored.” That’s how we end up with white artists creating such harmful and disrespectful things, like the sculpture of slain Ferguson resident Michael Brown by Ti-Rock Moore and the scaffold by Sam Durant [built near the site of one of the largest mass hangings of indigenous people in U.S. history]. The beauty and power of the art comes through the respect we bring to our collaboration.

Rewire: You’re best known for your portraits. How did that body of work begin?

MB: One of the first portraits I did was of CeCe McDonald. At the time, nobody knew about CeCe and her story outside of a very small network of trans justice organizers and allies.

I thought about creating that portrait of her for a year. I reached out to my friend Miriame Kaba, who does incredible transformative justice work with Survived and Punished and Project Nia. I asked her what she thought and she was like, “Do it!” I asked some other folks the same question, and these relationships have become an informal advisory committee of people who help me make these choices.

In 2013, I shared CeCe’s portrait on Trans Day of Remembrance (TDOR), November 20 each year, because at that time, TDOR was the only annual event that specifically focused on trans people. I didn’t have any aspirations for what would happen besides lifting up her story, but people were really feeling it. Within a week, it received more than 400 shares on Facebook.

Creating and sharing CeCe’s portrait was a learning experience for me about the power of using text and visual art together, to tell stories that can sometimes be a heavy lift for people in terms of holding all the layers of stories together. Telling stories through art and using social media makes it easy for people to soak it up. And that’s the gem for me: creating work that is both artistically and politically powerful and accessible.

Rewire: How do you choose whom to depict?

MB: There are many different ways that can happen. Because I’m a white person trying to be useful in racial justice movements, my work happens through relationships and collaborations. A lot of my work comes out of direct requests. Folks often contact me through social media to do portraits of people in their communities who are incarcerated or detained or who’ve been murdered. We work together to use the art to generate action like signing petitions for parole or raising funds for bail or funeral expenses. They get the final files and prints and can use the art however they want. If they want to sell T-shirts to support their organizing group, go for it. I just want the art to have as much utility as possible for the movement.

My goal is to make something that they love, and that makes them feel honored and seen. I also want to make something that pushes my skills and that I feel proud of as an artist.

I also get requests from organizers or organizations in specific communities—so there’s always a chain of accountable relationships. For example, last year, Black Lives Matter organizers asked me to do portraits of some of the Black trans women and femmes who had been murdered. They were specifically interested in using those images on signs at a rally in San Francisco to bring a message of #SayHerName that included Black trans women and femmes. It was an incredible and powerful invitation. Those are the times when I’m canceling everything and just making the art.

When people saw those portraits, I started getting a flood of requests from across the country, from trans organizers and family members, asking for art for actions, fundraisers, and memorials.

Usually when someone is killed, it immediately washes through trans social media networks and it’s really devastating. I’ll see the news, and I feel kind of numb. But the practice of quickly drawing someone who’s been killed feels so sacred and spiritual and intense for me. I’m trying to connect with them so that their humanity and spirit can come through the drawing and move people to rise up against this state of emergency for trans women and femmes of color. It’s disgusting that the entire LGBT movement is not mobilizing around this crisis.

These portraits are a channel for that collective grief and rage.

Interested in learning more about how artists and organizers can build deep, collaborative relationships for social justice? Read “How to Reimagine the World: Collaboration Principles for Artists and Social Justice Organizers.” This document was created by Bazant, Forward Together, and CultureStrike.