Virginia Ballot Proposal Could Cement Anti-Union Law in State Constitution

Not only are people in "right-to-work" states more likely to hold low-wage jobs, these policies have had negative effects on access to health care and other quality-of-life measures.

Labor rights advocates are fighting a proposed constitutional amendment in Virginia designed to weaken unions and further promote “free riding” among workers in the state.

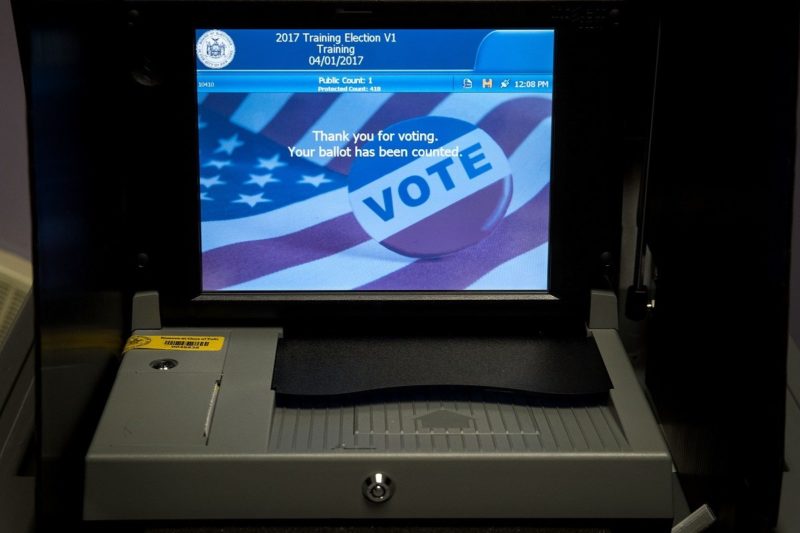

Voters on Tuesday will decide by ballot measure if the state’s so-called right-to-work law will be enshrined in the Virginia Constitution, which would make it more far more difficult to repeal.

If the amendment is approved, the policy could only be changed or abolished by voter referendum, according to the Virginia Department of Elections. The process would also require passage in the General Assembly, which is controlled by Republicans.

“Right-to-work” has been a Virginia policy since 1947, prohibiting employers from entering into labor agreements that require union membership to qualify for employment. The law, pushed across the nation by legislation mills opposed to collective bargaining rights, bans union membership from being a “condition of employment or continuation of employment by such employer.”

Virginia lawmakers in February passed a resolution along party lines to put the measure on the ballot, the Washington Post reported. The Virginia AFL-CIO opposes the amendment and has launched a major effort to educate voters on the proposal.

Lorne H. Seay, secretary-treasurer of the Virginia AFL-CIO and a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 26, wrote in a Roanoke Times column that the “right-to-work” ballot measure, known as Amendment 1, was a “waste of time.”

“Amendment 1 was designed by big business to stifle our voices—as workers and as voters—and is nothing more than the latest move in a political game for certain members of Virginia’s General Assembly,” Seay wrote.

The anti-union law prohibits unions from collecting any type of fee from non-members, according to Seay, even though unions spend “tremendous resources to negotiate a contract, administer benefits and retirement plans and represent [non-members] in grievance procedures.”

“No other member organization or club works this way,” Seay wrote.

Opponents of similar measures have noted that people living in states with “right-to-work” laws earn less than workers in states without such laws in place.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2014 suggested workers in “right-to-work” states make, on average, about 12 percent less than their peers in other states.

People in “right-to-work” states are more likely to hold low-wage jobs, according to data from the Corporation for Enterprise Development. For example, in Michigan, a GOP-held “right-to-work” state, about 25 percent of the state’s jobs were considered low-wage positions in 2013. That number was 15.7 percent in Massachusetts, which does not have laws against labor unions.

“Right-to-work” policies have had negative effects on wages, income, access to health care, and other quality-of-life measures, according to statistics from the AFL-CIO.

Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, and West Virginia have all passed laws created to weaken labor unions in recent years. A majority of states now have these anti-union measures in place.

Virginia Senate Minority Leader Richard L. Saslaw (D-Fairfax) told the Daily Progress that the anti-union policy was not “under attack,” as lawmakers had not initiated a bill to repeal the law during his decades-long tenure.

Supporters of the ballot measure include the Virginia Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Business, reported the Daily Progress.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the federal agency overseeing labor laws, requested legal briefings last year on labor union fees and said it would examine “right-to-work” laws.