For Native Women Seeking Abortion, Hyde Amendment Is Another Broken Promise

In my work caring for Native American women relying on federally provided insurance in northern Arizona, I meet patients who are shocked when they learn that abortion care is not covered. They are accustomed to receiving care through the Indian Health Service and the centuries-old promise that tribes will have a special government-to-government relationship with the United States.

This is the second part of a five-part series, published in partnership with Physicians for Reproductive Health, exploring how the Hyde Amendment negatively affects different populations in the United States.

Through the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, Native Americans are entitled to care provided by the United States government.

Delivered by a tribe or the Indian Health Service (IHS) division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, this care is meant to cover a Native American woman’s health care throughout her lifetime, including her own birth, her childhood vaccines, and as she matures, her reproductive health care. This insurance—this promise, if you will—provides a range of services relating to contraception, pregnancy, and safe infant delivery.

Unfortunately, there is a gaping hole in this coverage: Native American women do not have access to abortion coverage. And the Hyde Amendment, a rider on various federal budget funding bills, is the root of this injustice.

Hyde stipulates that federal government funds may only pay for an abortion in the case of incest, rape, or if the pregnancy threatens the mother’s life. A woman who receives her health benefits through the federal government must pay for an abortion with her own money, even when that insurance covers every other health-care need.

This causes an enormous barrier to Native American women who use the Indian Health Service as their only or primary health-care provider. By virtue of using the IHS, they don’t receive the same access to abortion care as women who get their health insurance coverage through other means.

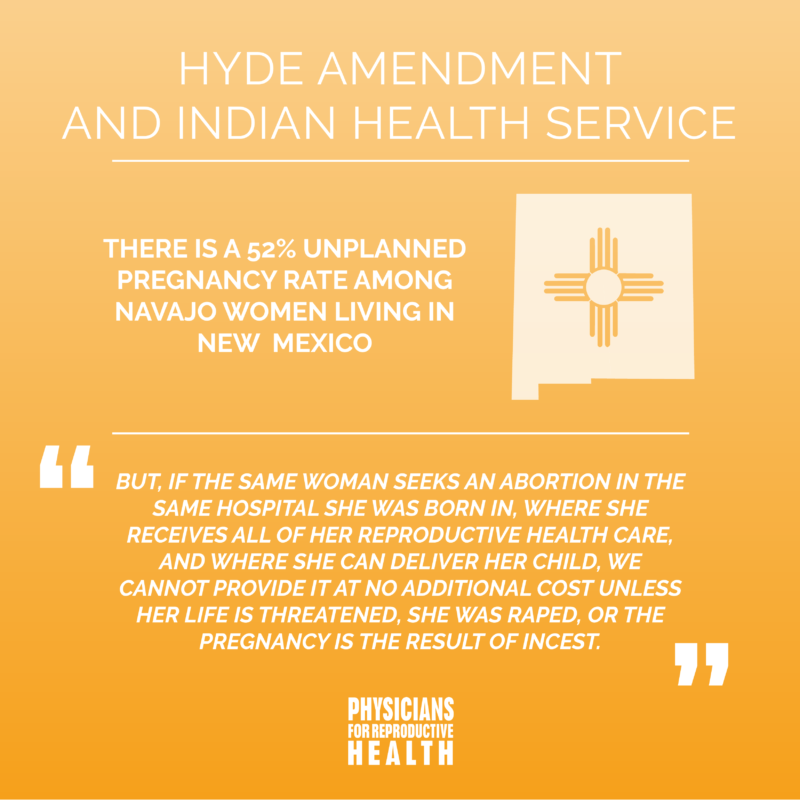

Though there’s not enough research about Native women’s reproductive health needs, we know that they are likely to have high rates of unintended pregnancy. A report published by the Navajo Nation in May states that Navajo women in New Mexico reported an unintended pregnancy rate of 52 percent. This is much like that of our nation as a whole, and one can extrapolate that some Native American women will also seek abortion for unintended pregnancies.

In my work caring for Native American women relying on this federal insurance in northern Arizona, I meet patients who are shocked when they learn that abortion care is not covered. They are accustomed to receiving care through the IHS and the centuries-old promise that tribes will have a special government-to-government relationship with the United States.

A patient recently came to me with an unintended pregnancy. She was working to overcome substance abuse and looking for information about her options, including abortion.

I carefully explained the state law mandating that she hear scripted information at least 24 hours in advance of her procedure, and I emphasized that she was responsible for paying for the abortion.

She said to me, “What about my insurance? I have insurance.”

I explained that abortion is not covered, though she would not be denied care in any other circumstance. If a Native American woman has a continuing pregnancy, physicians and health-care professionals are there. If her child has an emergency, we are there. If she has appendicitis, we are there.

But, if the same woman seeks an abortion in the same hospital she was born in, where she receives all of her reproductive health care, and where she can deliver her child, we cannot provide it at no additional cost unless her life is threatened, she was raped, or the pregnancy is the result of incest.

Abortion is a legal medical procedure, and my patients should not have to justify their need for one. A woman’s life should not have to be in jeopardy for insurance to pay for an abortion, nor should they have to find themselves pregnant through the obviously tragic and traumatic experiences of rape or incest to have this care covered.

My patients should not have to justify the reasons they would like an abortion to me, other medical providers, or their government. The hospitals in which they receive all other gynecologic health care should provide this service.

In a state that allows no funding for abortion through the state’s Medicaid program except for those in the circumstances described by the Hyde Amendment, it is urgent that the federal government end Hyde to provide the procedure legalized more than 40 years ago. It’s time to take away this burden.