‘I Burn, and I Hope’: Today’s Writers Revisit ‘The Fire Next Time’

It’s 2016, but the world James Baldwin described in the early 1960s seems no different from the world we live in now.

The first essay in James Baldwin’s 1963 book The Fire Next Time is a letter to his young nephew regarding the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the racial discrimination Baldwin’s nephew will face. Baldwin details the hate his nephew will encounter, and the people who will only see him, a young Black boy, as an animal. But Baldwin’s warning is not used as a fear tactic; rather, Baldwin pleads for his nephew, and for Black youth as a whole, to live with compassion, to survive “for the sake of your children and your children’s children.”

He ends the book by demanding everyone—everyone meaning Black and white people who are conscious of U.S. race relations—change the minds of hateful people. “If we do not dare everything,” he writes, “the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by the slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, / No more water, the fire next time!”

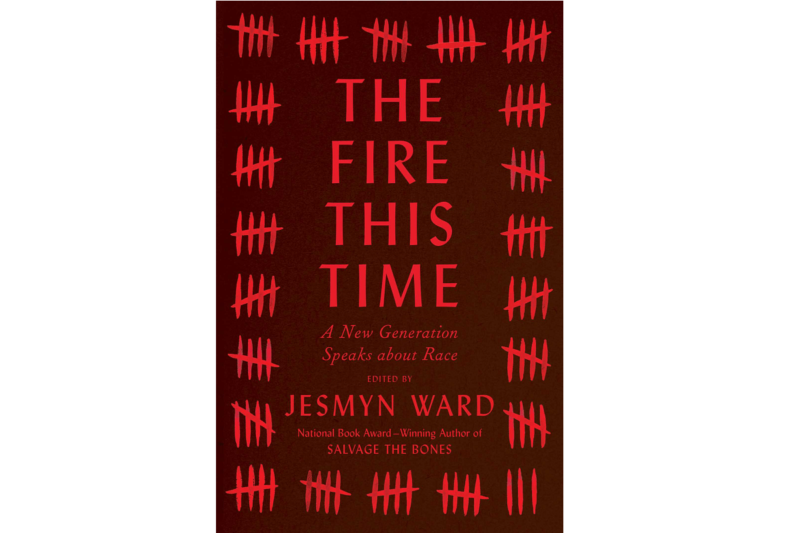

Now Jesmyn Ward—an English professor at Tulane University and a recipient of the 2011 National Book Award for Fiction with her second novel, Salvage the Bones—has compiled a collection of 15 essays and three poems (ten of which were written specifically for the book) that arrives 53 years later, at the time of the fire Baldwin forewarned. Not every person has pushed to bring an end to racial injustice, and so everyone is burning. But so long as there are activists, philosophers, and artists, there is always hope we will one day pull ourselves out of the flames: That is the message I took away from Ward’s The Fire This Time. The collection acknowledges the pain and brings the reader a sense of hope that the fire this time is not permanent.

Featuring great contemporary Black writers like Kiese Laymon, Claudia Rankine, and Kevin Young, The Fire This Time uses Baldwin’s thoughts on race to discuss current struggles and Black people’s dogged determination to love each other amid centuries of hate.

Released today on what would have been Baldwin’s 92nd birthday, the book is grounded in the country’s history to help readers better understand the context of our present moment. As Ward states in her introduction, “We must acknowledge the plantation, must unfold white sheets, must recall the black diaspora to understand what is happening now.”

Slavery may have been abolished more than 150 years ago, but, as the book suggests, the world has not overcome its racist roots, nor has it granted Black people any new means of safety.

When I initially sat down to write this review, the Freddie Gray case had just concluded with zero convictions against the Baltimore, Maryland, officers involved in the death of the 25-year-old Black man. Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke had addressed the acquittal to a resounding applause at the Republican National Convention. Meanwhile, Black parents still live in fear for their children playing in the park, street, or pool. Despite claims of a “post-race” society—one in which people are not discriminated against or murdered because of the color of their skin—the targeting by law enforcement of some racial groups over others remains rampant. It feels as if, especially for those with power, the Black body is still another beast to be tamed. It’s 2016, but the world Baldwin described in the early 1960s seems no different from the world we live in now.

This connection between the past and present is the central focus of Claudia Rankine’s essay “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning,” when she talks about how shortly after she was born four Black girls were killed at an Alabama Baptist church on September 15, 1963, and how 52 years later, “for African-American families, this living in a state of mourning and fear remains commonplace.” Shortly before her essay originally appeared in the New York Times, on June 17, 2015, nine parishioners were shot and killed at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. “Dylann Storm Roof [the shooting suspect] did not create himself from nothing,” she writes. “Every racist statement he has made he could have heard all his life. He, along with the rest of us, has been living with slain black bodies.”

This association is also made in Clint Smith’s poem, “Queries of Unrest,” in which the author writes, “Maybe I come from a place where people / are always afraid of dying.”

Despite the dark nature of the topics addressed in the book, a thread of hope is weaved throughout the entire collection. As Ward writes in her introduction,“I burn, and I hope.”

The Fire This Time isn’t interested in creating plans on moving forward as much as it is about discussing the humanity of Black people.

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers questions historians’ portrayal of Phillis Wheatley and her husband John Peters, asserting that their relationship could have been loving rather than tumultuous; Kiese Laymon thanks OutKast and his grandmama for letting him find his “funky” voice; and Emily Raboteau writes on the importance of murals in urban communities that she photographed around New York, which teach civilians about their rights when engaging with the police.

Amid loss and fury, love binds Black communities together. Our love for each other is what keeps the fire burning as we are shouting for our lives to matter.

However, The Fire This Time is not just a book for those inside the diaspora; Ward urges those who don’t identify as Black or consider themselves part of the diaspora, and those who lack understanding of the Black Lives Matter movement, to read this book and educate themselves on the ways in which Black people are unequivocally human. The collection could change the minds of those who see the Black community, and especially the Black Lives Matter movement, as menacing. It’s an educational and emotional read that shows Black people are hurting and loving simultaneously. Kiese Laymon says it best in his essay “Da Art of Storytellin’ (A Prequel)” when he writes, “I’m going to tell Grandmama that her belief is the only reason I’m still alive, that belief in black Southern love is why we work.”

The Fire This Time develops a kinship with non-Black folks through the use of the collective “we.” For example, Isabel Wilkerson speaks to Black people about the continuation of trauma against us and in “Where Do We Go From Here?” (which originally appeared in Essence magazine’s special Black Lives Matter issue). Or Carol Anderson’s “White Rage,” where she takes a historic look at white supremacy in the wake of Black death: “When we look back on what happened in Ferguson, Missouri … it will be easy to think of it as yet one more episode of black rage ignited by yet another police killing of an unarmed African American male.” Instead, Anderson argues that what we’ve seen is an example of white rage, a backlash from white people who have “access to the courts, police, legislatures, and governors,” and can hurt Black communities through means of law and order.

The diversity of perspectives in The Fire This Time is necessary, as the collection seeks to show its readers that Black life, like Black art, can never be extinguished.

In fact, The Fire This Time places a strong emphasis on the difference between life and Black life to ensure the reader understands it, and never forgets the way race alters everyone’s living. The difference between life and Black life is that the latter is always questioned, threatened, or destroyed, due to racism. Whether attending a funeral, walking at night, or even listening to music, a Black body gives ordinary life new context.

The authors of the pieces that fill The Fire This Time have come together, under Ward’s direction, like a family sharing their fears, their rage, and their happiness. Reading through the collection felt like sitting through a discussion with aunties and grandparents. The reader must hear her elder’s stories, which are honest and analytical, comical and devastating.

As Edwidge Danticat writes in the final essay of the book, “Message to My Daughters,” Black people want a future where our children “have the power to at least try to change things, even in a world that resists change with more strength than they have.”

The Fire This Time will not leave you feeling completely hopeful of the future—it is not naïve in its optimism—but it does suggest that there is always room for societal change, so long as we continue fighting for it. Like The Fire Next Time, this book still hopes for when the fire will bring peace. “When that day of jubilee finally arrives,” Danticat writes, “all of us will be there with you, walking, heads held high, crowns a-glitter, because we do have a right to be here.”