Only Through Becoming a Parent Have I Been Able to Let Go of My Grief at Losing My Own

Having a baby has brought me back to the present in the most profound way I could ever imagine.

Today is my 21st birthday, of sorts.

Twenty-one years ago today, my father died. Twenty-one years ago today, I watched the perspiration puddle in the dent below his Adam’s apple for the last time. I watched him lick his parched lips. I saw the crisp hospital sheets sag with his sweat—sweat from his poor body, riddled with cancer, emaciated, aged, and somehow bloated, all at the same time.

Days earlier, when I brought his dictaphone to the hospital, with the miniature tapes that used to go into answering machines, I held the recorder to his mouth and—because I, his 14-year-old baby girl, asked him to—he said, slowly, carefully, effortfully, while looking me straight in the eye: I love you, Sharona. I. Love. You.

For the last time.

I was 14, and it was the end of childhood. Childhood had been ending for a while, during the months of illness, false hopes, and horrible disappointments. The tumors were in his kidneys, and they were growing. They were shrinking. They were back. They were in his chest, his brain. The radiation was working (“Look, my girl, they drew a target on my head!”); it wasn’t working. I learned gallows humor. I learned to pretend there was nothing unusual about finding my father marooned on the staircase at home, unable to make it to the top. Both of us choking back sobs as I said, “Wait, Dad. Wait,” and walked myself—calmly, steadily, like you’re meant to do when walking around a swimming pool—next door, and softly explained to our neighbor, Mr. Wood, that we needed his help. Alarm shadowed his eyes, and Mr. Wood grabbed his keys and my hand, and back we went to our house. The three of us sweated and grunted our way up the stairs, around the landing, into my parents’ room, and laid my dad in bed.

Then Mr. Wood—Tony, to my dad—stood there, awkward, silent and sad.

“I’ll see you ‘round, Terry.”

“Yeah, see you ‘round, Tony. Thanks mate.” Breathless. Relieved. Humiliated.

“Yeah, no worries, mate.” A hesitation. A shattering pause.

And he left, because Tony is a decent man, and he knew we needed to be alone.

People try so hard to be kind to grieving kids, but they’re bad at it. They don’t know how. They do things like invite you to the movies, but end up taking you to see Casper the Friendly Ghost. Then they’re speechless afterward, because what kind of an idiot takes a kid to see a movie about a little boy who died, the day after her father died?

Kind idiots. That’s who. We’re all idiots in the face of that sort of meaningless tragedy. Because it shouldn’t happen. And yet it does, all the time. And still, we don’t know what to say, or do. Or whether saying or doing are what’s called for, what’s wanted or needed—because we also find it so terribly hard to ask, and of course, how is a child supposed to know what she wants or needs, other than for none of it to be true?

It’s the powerlessness that does it, breaks your confidence in the order of the world. The helplessness. The total lack of agency. Oh, of course, you can fool yourself by talking yourself into and out of all sorts of mental and emotional contortions. This will make me stronger. The brightest candles burn out first. Ultimately, what reveals itself is that time is both the oppressor and the savior: You must wait out the grief, but you don’t know how long it will hold you hostage. And you don’t know how damaged you’ll be once it’s done with you. And there is very little you can do about any of it.

For me, it turns out, it took about 20 years. There were ten years of numbness, of deep denial. I was crushed, I remember, when Australia added a digit to the beginning of all phone numbers, some years after my dad died. I was distraught thinking that he wouldn’t know our phone number if he came back. If he came back. I caught myself in that delinquent thought. Consciously, you know these things—he’s dead, he’s gone, he will never, ever be back—but your subconscious rebels, riots even. In dreams, in daydreams, and sometimes, in little jabs that wind you as you go about your day. Your subconscious refuses: This loss, I will not accept.

The next ten years were a mix of depression, anxiety, and an all-encompassing bewilderment that these emotions were now cascading over me, unmitigated, untidy, unpredictable. I did and said things that I found excruciatingly embarrassing, because I could no longer hold myself under such tight, absolute control. Like water in an old pipe, the emotions had found ways to leak out at weak points. At times, I felt my structural integrity was compromised. I was, in short, afraid that I was about to collapse. Therapists would ask, “And what would happen if you did collapse?” and I would stare at them, in disbelief at the premise of the question: That will not happen. Cannot happen.

We are given a tiny sliver of time in which it is generally acceptable to display the symptoms of grief. Six weeks after the death of a loved one, few people will realize you are sad because of grief. Six years later—or 16 years—gushes of grief can seem mad and unhinged. You’ll get more sympathy for a broken bone than a broken heart. People will wonder: When will you “get over” the loss?

In writing personal pieces like these, there is always a judgment about what to say, and that is really about how much to hold back. I take the view that it is necessary to hold most of it back. Not for shame or fear, but because there is a province of the self that is sometimes better left untrammeled. It’s as if there are parts of the self that risk oxidation by exposure to the air; like a delicate, old artwork, you’d see them for the instant before they cracked and flaked away.

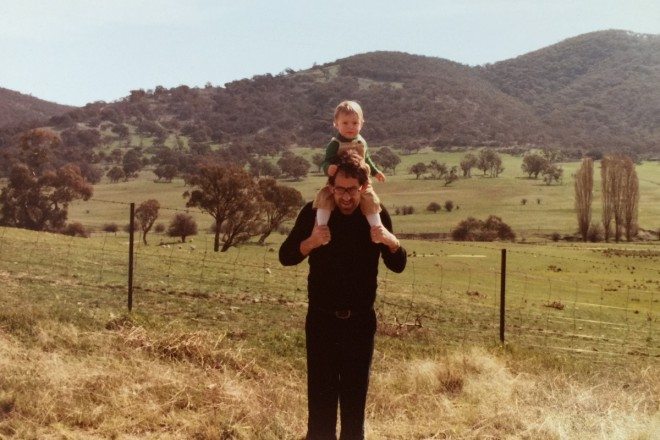

What I wanted to share here is a celebration. Not of my 21st birthday as a child of grief, but a different birthday: the birth of my daughter late last year. For me, it has only been through becoming a parent that I have been able to let go of the grief over my own parent.

Why?

Don’t I wish he were here to see me as a mother? To know his grandchild, to give her all the things I forbid him to give her, and to teach her dirty jokes that will lead teachers to place her in detention and make me laugh hysterically when I find out why?

Of course I do. Of course, of course.

But it’s not about that. It’s about a radical shift in outlook, and one that I suspect is a key to forcing grief to move out of the way, to the extent you can. Maybe just to move it enough so that some light gets past its shadow.

Having a baby has brought me back to the present in the most profound way I could ever imagine. In fact, I couldn’t imagine it; it has taken me by surprise. Because I know she will need to eat, and I will feed her, I know I will see her every few hours. And I actively, constantly, intensely look forward to that. I look forward to changing her diapers, because I can blow raspberries on her belly and possibly, hopefully, make her laugh. She will need her nap, and then she will wake up, and she will look for me. And I will be there. She will need a bath before bed, and to be nursed and hugged and held and loved. And I will be there.

Never in my life have I lived so joyously in the present, looking forward to every increment of the day. To be able to share it with a partner who is just as overjoyed and present is more than I ever hoped to have. I know that my daughter will have a love for her father just as strong as mine was for the one I lost.

My message for those who grieve is bound up in this. We are taught to mourn, to pine, and never to forget.

While grief will hold onto you for as long as it wants, try not to hold onto it so hard. There is no honor or reward in gripping the memories of lost loved ones so tightly that your knuckles are white and your soul is sore, and you grow tired. Better to focus on what you do have, on the small things, the tiny things—whatever can or does bring you joy. That, after all, is what any parent wants for their child—that they live a joyful life, not one that longs mostly for what isn’t there.