Exploring Jewish Identity Through the Eyes of Women Artists

According to scholar Tahneer Oksman, women illustrators from the United States and Canada use their drawings to make sense of their religion, culture, and sometimes complicated relationships to Israel.

The seven women whose graphic autobiographies are deconstructed in Marymount Manhattan College professor Tahneer Oksman’s “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs” are all successful North American artists. But to a one, they have had to confront and surmount anti-Semitism and sexism. Alongside common decisions about career and lifestyle, each illustrator has had the added task of determining how, or if, she wants to relate to contemporary Jewish life, and how, or if, she wants to align herself with the state of Israel.

Oksman’s narrative presents these conundrums honestly, if academically. She analyzes how the graphic works address the complications of being part of a secular, often-contentious, and non-monolithic Jewish community. Indeed, “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?” showcases the wide diversity among those who call themselves “cultural Jews,” women linked to their ancestors by blood rather than faith. Differences are highlighted, and the book asks important questions about bones of contention that the Jewish community must confront, from the conflation of Judaism with Zionism to the challenges that arise from persistent stereotypes about female Jews.

But as provocative as it is, the book also has deficits.

The book would have been enriched, for example, by a discussion of art created by women enmeshed in religious life, such as devout British cartoonist Keren Keet, who humorously depicts the high-wire juggling it takes to balance raising children with paid work and religious obligations. Similarly, there are no depictions of women who are minimally observant but not devout in either Oksman’s text or the accompanying visuals. Furthermore, it is unclear how Oksman selected the artists she featured, since there are many other Jewish women in the graphic arts—among them Leela Corman, Miriam Katin, Diane Noomin, Racheli Rotner, Ariel Schrag, and Ilana Zeffren.

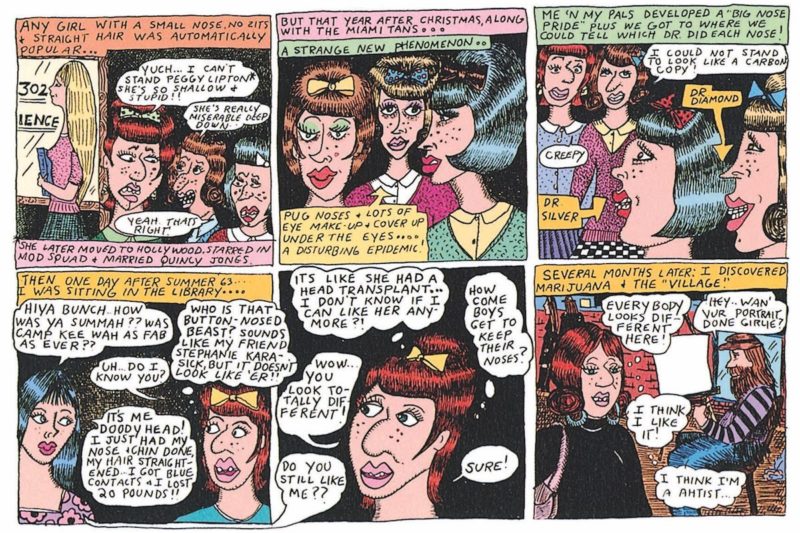

The book opens with a discussion of “the serial selves” of Aline Kominsky Crumb, who was born into an upper-middle-class Long Island family in 1948. Her multiple self-portraits illuminate key developmental milestones, from her refusal to get a nose job or straighten her hair—acts that separated her from every other ninth-grade girl in her class—to her relief at finding other “freaks” in New York City’s Greenwich Village in the late 1960s and ’70s. One 1989 illustration looks back at the cookie-cutter sameness that marked her adolescence and pointedly asks why “boys get to keep their noses.”

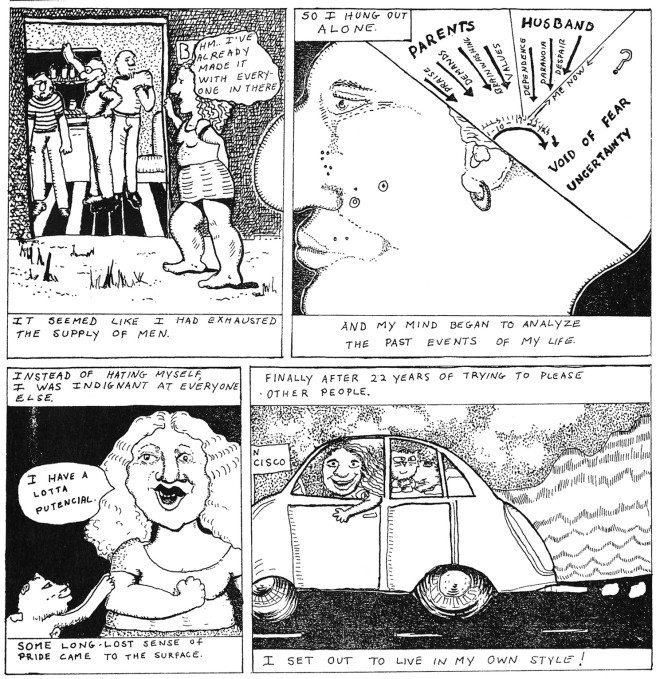

This seemingly innocent question straightforwardly pinpoints the sexist expectations of the early 1960s and reveals an astute observation about the double standards that young women—indeed all women—faced then, and continue to face today. In fact, one of Kominsky Crumb’s earliest cartoon alter-egos, Goldie, became an exemplar of sass when, in 1972, she declared that “after years of trying to please other people, I set out to live in my own style.” She is smiling in the drawing, driving off in a sports car “void of fear.”

Then there’s the issue of having and being a Jewish mother. “As an identity that has been chosen by her, like becoming a wife and artist, motherhood has the potential to signify a role that allows Kominsky Crumb to feel free and further indulge in her own style,” Oksman writes. “Yet as her comics reveal, motherhood is always inevitably associated with inheritance—the inherited relationship she shares with her own mother as well as stereotypes about Jewish mothers, not to mention mothers more generally, that characterize much of popular North American art and literature.” For Kominsky Crumb, this requires taking on the smothering Jewish mama stereotype at the same time that she grapples with her own fraught relationship with an overbearing mom.

Additionally, the anti-Semitic trope that describes Jewish women as gold-digging, self-centered, vain, and materialistic is fodder for Kominsky Crumb. She pokes fun at this hackneyed notion while simultaneously critiquing her Jewish peers for elitist and “princesslike” behaviors. It’s a nuanced and critical posture revealing her placement both within and outside Judaism.

Other Kominsky Crumb drawings present what Oksman calls “the struggle to negotiate between inherited and chosen identities,” that is, responsibility to the tribe—the large Jewish diaspora—versus responsibility to the self.

This stance is taken by other Jewish feminists as well. In fact, Kominsky Crumb’s younger counterparts mine similar turf—and from a similarly distanced place. In Vanessa Davis’ 2010 graphic memoir Make Me a Woman, she reflects on her bat mitzvah’s material excess. According to Oksman, when Davis discovered the class privilege of her upbringing, she had to come to terms with the “realization that it was not a universal background for all American Jews.” This understanding reoriented Davis “in relation to her own history and [set] her on a path to understanding her Jewish identity as highly individualized or a matter of location.”

Similarly, artists Miss Lasko-Gross and Lauren Weinstein explore what it means to be culturally Jewish and connected to the community by ancestry while choosing to remain non-religious. How this stance has influenced their values, morals, and relationships throughout their lives is described and analyzed.

The goal of their autobiographical stories seems geared to evoking the reader’s empathy, and Oksman’s narrative and the accompanying graphics are deeply resonant. Still, it’s standard coming-of-age stuff, and despite the specific cultural angel, it will feel familiar.

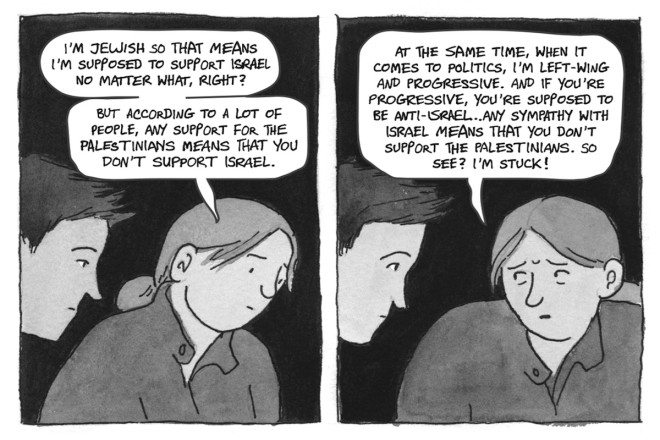

More compelling is the book’s look at how Sarah Glidden and Miriam Libicki tackle the subject of Israel. Glidden’s 2010 How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less and Libicki’s ongoing jobnik! series address the ambivalence of many secular American and Canadian Jews toward the Jewish homeland.

For Glidden, a free ten-day trip to Israel sponsored by Taglit-Birthright, an organization that brings scores of 18-to-26-year-old Jews to the “promised land” for a highly orchestrated tour, is an opportunity for adventure, albeit one rife with political discomfort. Expecting a “regional propaganda tour,” the self-described progressive humanist initially remains aloof from her fellow travelers. Later, however, she realizes, as Oksman puts it, that “approaching a so-called unfiltered look at Israel requires not isolation but connection with others. Avoiding the biases of people around her is not enough; she must explore them as well as consider them in relation to her own biases,” especially as a U.S.-born critic.

Miriam Libicki, on the other hand, served in the Israeli Army subsequently produced issues of the jobnik! comic series since 2003. As a dual U.S.-Israeli citizen, she volunteered for the Israel Defense Force in the late 1990s, and her graphics present her transition from gung-ho militarist to anti-occupation “peacenik.”

Libicki also addresses gender discrimination. She was not only sexually harassed by male IDF soldiers, but was assigned mundane secretarial duties rather than the more challenging work she craved. In addition, Libicki writes that her contemporaries saw her as bizarre: “For the Israelis, being in the army is an inevitable fact of life,” Oksman notes. “Their identities as soldiers are, by necessity, integrated into their identities as young people socializing with one another. For Miriam, growing up in Ohio, being in the Israeli army is a significant act. It represents a sacrifice she has chosen to make .… Miriam’s unquestioning affiliation to Israel and the Israeli army therefore actually distanced her from those around her,” and left her with ample time to think about both her isolation and politics.

There is pain in Libicki’s account, just as there is pain in the other stories featured in ”How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?” Indeed, as each woman’s story unfolds, a profound sense of disequilibrium surfaces. This is too bad, since the joy of belonging—the comfort found in repeated rituals, food preparation and consumption, and sisterhood—is missing from most of the accounts. Oksman writes that the seven cartoonists featured “adopt notions of Jewish difference to establish an encompassing metaphor for Jewish American women’s marginalized status within an already tenuously defined and situated community.” Sadly, in focusing almost exclusively on distance, the connections that bind Jewish women to one another, and that exist between Jews and the rest of humanity, fall by the wayside.