Unintended Pregnancy Reaches 30-Year Low, But Racial and Economic Disparities Persist

Low-income women and women of color are still more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy than women of higher economic status and white women.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

Unintended pregnancy in the United States reached a 30-year low in 2011, according to a new analysis from the Guttmacher Institute. Among women ages 15-to-44, it fell from 51 percent of all pregnancies in 2008 to 45 percent in 2011.

The sharp decline correlates with an increase in contraceptive use over the same time period, likely from expanded access to birth control, which is supported by the 2010 health-care reform law. More women have been able to delay or prevent pregnancy and build the families they want as a result of improved access to contraception, the authors suggest.

But, it’s not all good news. Long-standing racial and economic disparities remain. Low-income women and women of color are still more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy than women of higher economic status and white women.

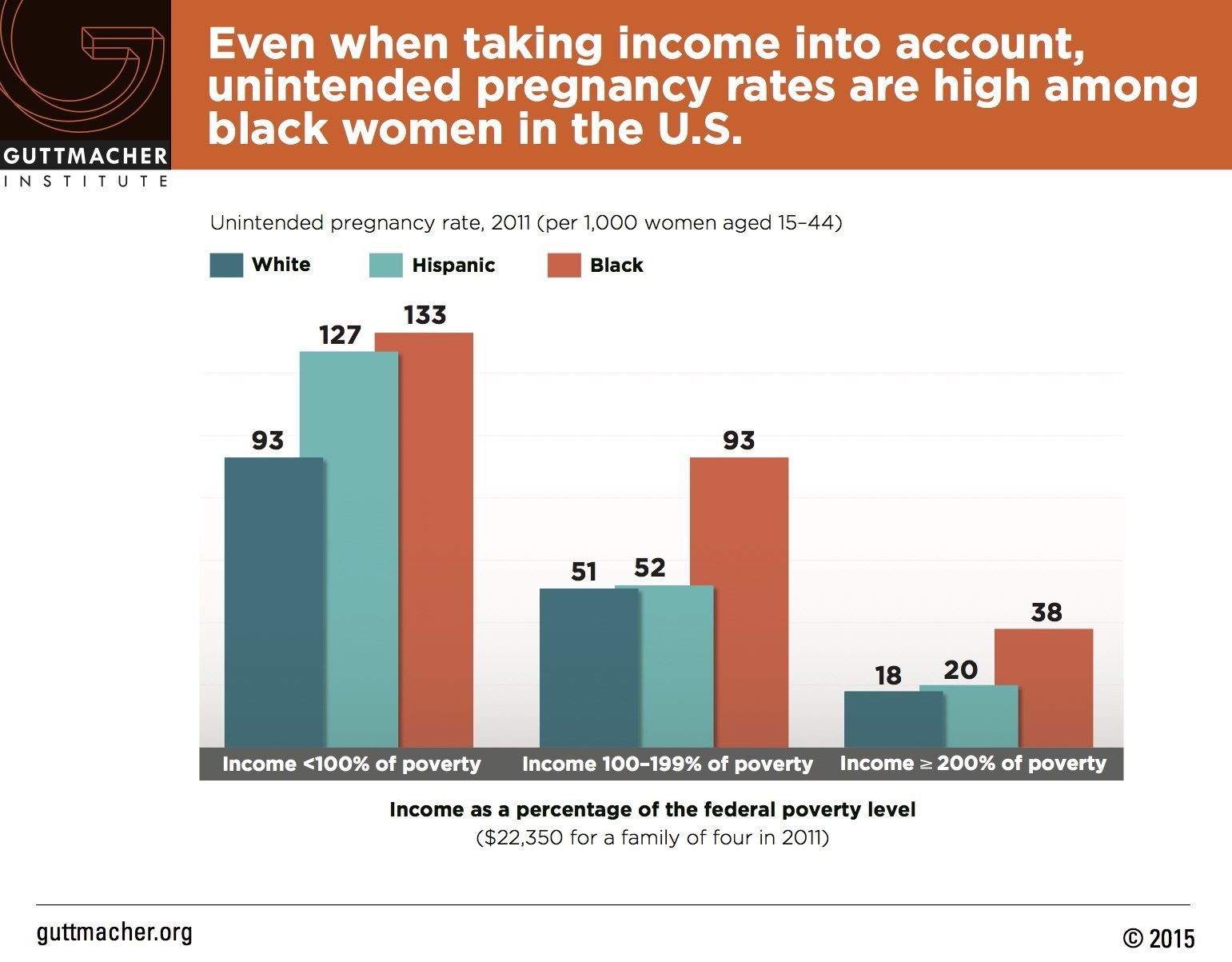

According to the analysis, titled “Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011” and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, women living in poverty in 2011 were five times more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy than higher-income women. Black and Hispanic women were roughly 2.5 times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to experience an unintended pregnancy. And even when income was taken into account, Black women had higher rates of unintended pregnancy than both white and Hispanic women.

The birth control benefit in the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—which requires that most private health plans cover contraception without a co-pay, as Medicaid has done for years—will likely contribute to a decline in rates of unintended pregnancy. Even so, why are racial and economic gaps remaining relatively unchanged?

In order to see progress for women of color, we must overcome social and systemic inequity that contributes to varying levels of health-care access, contraceptive use, and unintended pregnancy.

The Guttmacher analysis does not examine the root causes of disparities in reproductive health according to race and class, but the researchers acknowledge that such disparities are endemic in the United States. In an email to Rewire, Dr. Lawrence Finer, director of domestic research at the Guttmacher Institute, shared, “These disparities … stem from broader and persistent economic and social inequities, including access to education, well-paying jobs, safe neighborhoods, and quality health coverage and care.”

These disparities won’t disappear by themselves. Systemic change will require targeted efforts to expand Medicaid, improve health-care access and quality, and close racial disparities in income and wealth.

Medicaid Expansion

Women of color, particularly low-income Black and Latina women, do not benefit from the ACA the same way white women do. Women of color are still more likely to be uninsured, which may be attributed to lower incomes and lack of access to employer-sponsored health insurance. Moreover, the majority of the 17 states that have refused to expand Medicaid (concentrated in the South) have a higher percentage of residents of color, further undermining policy gains with respect to birth control access.

As a result, some women of color may be unable to afford the birth control of their choice or access the most reliable methods. Highly effective methods like the intrauterine device and implant are often more expensive up front than other methods like the pill or the ring. Furthermore, women without consistent access to birth control may rely on condoms, withdrawal, or emergency contraceptive pills, which simply aren’t as dependable.

Medicaid expansion would dramatically increase access to birth control for low-income women, reaching people with an income level at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level, which is $24,300 per year for a family of four. Some childless adults fall into what is known as the Medicaid coverage gap, which Medicaid expansion addresses: They are not eligible for Medicaid and do not earn enough to receive subsidies to purchase coverage through the health insurance marketplace. As of 2015, 14.9 million people of color fell into that gap.

To make progress, all states should expand Medicaid to remove financial barriers to contraception so that low-income women and women of color can maintain their health and avoid unintended pregnancy.

Improve Care for Women of Color

Beyond expanding financial access to health care and contraception through insurance coverage, there is a real need to improve how low-income people and women of color experience and interact with the health-care system.

Historically, women of color have been used as test subjects and mistreated by the medical establishment. To this day, when some women of color seek care, they are met with insensitivity, disrespect, and neglect from health-care workers. Women’s experiences with the health-care system have been documented in films like The American Dream and No Más Bebés, and shared in a variety of reports. There is no doubt that some women of color avoid the health system altogether because of bad experiences with care providers or out of safety concerns, which can adversely affect their health status.

Ending racial discrimination in health care is an ongoing battle, but one that is key to meeting the needs of women of color and closing gaps in health outcomes like unintended pregnancy. The disproportionate rates of unintended pregnancy among women of color, who are already more likely to live in poverty than white women, may contribute to lower educational attainment and higher economic insecurity. Delaying, spacing, or avoiding pregnancy helped women to achieve their educational and career goals, according to research summarized in a 2013 report.

Close Racial Disparities in Economic Security

Lack of insurance coverage for contraception is further complicated by the fact that women of color disproportionately struggle under the weight of poverty. Some women of color simply don’t earn enough to make ends meet and may find themselves choosing between things like paying the bills to keep the lights on or paying for birth control.

Black and Latina women in particular have little to no accumulated wealth. According to a 2013 report by the Center for American Progress, single Black women have a median wealth of only $100 and single Latina women have a median wealth of $120, compared to $41,500 for single white women. It is imperative to close racial gaps in income and wealth through more equitable systems and practices.

As more and more people benefit from health-care insurance, we may continue to see greater contraceptive use and an increase in the rate of intended pregnancies. Lower unintended pregnancy rates are a good thing for women and families, but researchers, advocates, care providers, and policymakers must take heed to prioritize the needs of low-income women and women of color.

“The best way to continue the recent progress is to ensure that all women, regardless of income, race, or any other characteristic, have access to a full spectrum of health coverage, information, and services they need,” said Dr. Finer. Without efforts above and beyond what has already been done, racial and economic disparities in pregnancy will persist.

CORRECTION: This piece has been updated to clarify the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act on unintended pregnancy rates.