The Flint Water Emergency Is a Reproductive Health Crisis

Today, the entire nation is aware of the disaster. But for well over a year, residents in this city of some 100,000 people fought a lonely battle to convince the authorities that they were drinking, bathing, and cooking with poisoned water.

At first the signs were subtle—a slight discoloration of the tap water, a strange smell lingering in the shower stall or bathtub. Then the symptoms became more severe. Adults started to lose clumps of their hair and children broke out in rashes. Suspicions grew into fears, which were subsequently confirmed by studies. Families waited anxiously for test results to trickle in.

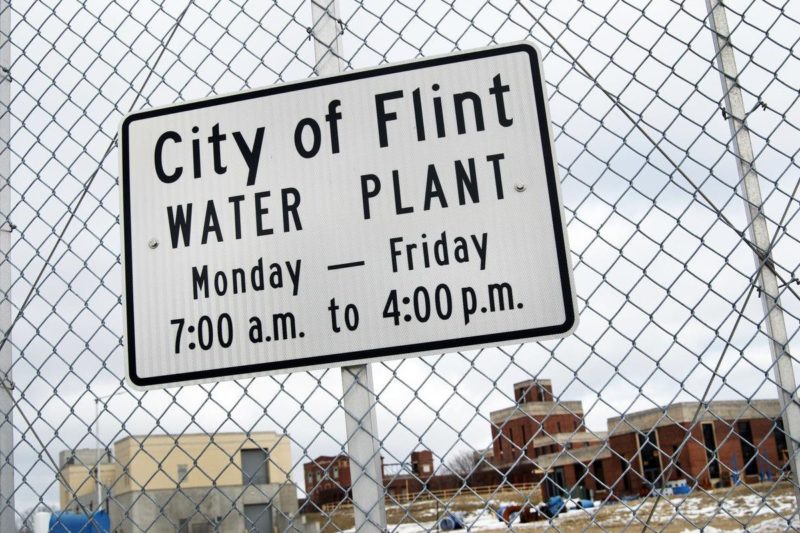

It all began in April 2014 when the city of Flint, under a state official, switched its water source from Lake Huron to the highly corrosive Flint River in a cost-cutting scheme aimed at saving $5 million in a two-year period. The chloride-heavy water quickly ate away at Flint’s aging infrastructure, leaching lead from the pipes into the water supply. Today, the entire nation is aware of the disaster. But for well over a year, residents in this city of some 100,000 people fought a lonely battle to convince the authorities that they were drinking, bathing, and cooking with poisoned water.

From the very beginning, women were at the forefront of the movement to raise awareness about possible lead contamination, demanding answers from officials and teaming up with independent researchers to conduct their own water tests.

As households continued to consume the murky, toxic water, mothers started noticing changes in their kids’ behavior, including slower cognitive capabilities, according to reports. Elderly people were developing lesions in their skin. Before long, local, women-led groups like Water You Fighting For and the Flint Democracy Defense League had begun to mobilize their communities to raise the issue as a public health crisis. Families came out to demonstrations holding samples of the discolored water and signs that said, “Stop Poisoning Our Children.”

“I remember one woman who would come out to some of the earliest protests—she was a senior citizen and each time she would show up with a bigger and bigger ball of her own hair,” Sylvia Orduño, an organizer with the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, said in an interview with Rewire. “She had this really long hair but pretty soon, I was able to see her scalp because she was losing so much of it.”

She said other women were panicking about rashes breaking out in their children’s genital areas. “And one mother even told me her 4-year-old was having trouble speaking: Like, there were words he knew but he was struggling to communicate them.”

Health-care providers, too, began noticing how their patients became particularly anxious about what the water situation meant for their family’s health and well-being.

“Soon after the switch we started noticing a difference in the communities we serve and the patients who were seeking care,” Sabrina Boston, manager of the Planned Parenthood Health Center in Flint, told Rewire in a phone interview.

In June 2015, a full year after Flint residents had first begun to consume lead-contaminated water, the Michigan chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union released a mini-documentary titled Hard to Swallow: Toxic Water Under a Toxic System in Flint. It featured several Flint residents, including LeeAnne Walters, whose five children started falling ill shortly after the switch in 2014. Anxious about her kids’ “scaly skin,” rashes, and rapid hair loss, Walters summoned city officials to test her tap water. The test returned results that showed lead levels at 397 parts per billion (ppb). By comparison, the Environmental Protection Agency warns that anything over 15 ppb can cause “irreversible” damage to a child’s brain.

Subsequent testing by volunteer researchers from Virginia Tech University showed Walters’ tap water to contain lead levels of over 13,000 ppb. According to this ACLU video, a lead-to-water ratio of 5,000 ppb is considered hazardous waste. Walters has since moved away from Flint, but her attempts to get to the bottom of her family’s sudden health problems have been widely recognized as instrumental in galvanizing national attention for the situation on the ground, which state and city officials had long sought to conceal.

Serious Consequences for Maternal and Child Health

Today, much of that cover-up is a matter of public record, with Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder (R) last week releasing official emails revealing his administration’s knowledge of the problem for well over a year.

On January 16 President Obama declared a federal state of emergency in the majority-Black city, days after Gov. Snyder had deployed the National Guard to assist in relief efforts, including distributing bottled water and filters to tens of thousands of households. Federal aid totaling $5 million—the maximum allocation possible under federal emergency laws—was recently made available to help mitigate the crisis. In addition, according to the New York Times, President Obama announced last Thursday Michigan could have immediate access to $80 million that had previously been earmarked for federal water infrastructure development. It is still unclear how this funding will be allocated.

Even as help pours in from around the nation, with big-name celebrities pledging tens of thousands of dollars in financial support, residents in Flint continue to suffer the health impacts of consuming and being in contact with lead-poisoned water, which has particularly serious consequences for maternal and child health.

According to the World Health Organization, there is no known “safe” blood-lead concentration, although the severity of symptoms and likelihood of longer-term impacts increase along with exposure. These include behavioral issues and reduced cognitive functioning in young children, as well as anemia, hypertension, and toxicity to their reproductive organs. WHO research also shows that high levels of lead exposure over a prolonged time period can severely damage a child’s brain and central nervous system, causing comas, convulsions, and in some cases death.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that pregnant women and lactating mothers who are exposed to lead are at heightened risk of gestational hypertension. And since lead can persist in bones for decades, especially in pregnant and lactating women, mothers and their babies remain exposed to lead long after external sources of contamination have been eliminated.

“This is a reproductive health crisis of monumental proportions that you would not expect to see in a developed country and certainly not in a state … like Michigan, which ironically is surrounded by one of the largest bodies of fresh water in the world,” Dr. John Hebert, director of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency Program at the Hurley Medical Center, told Rewire.

By his estimates, based on his department’s observations of the unfolding crisis, between 9,000 and 10,000 children, and at least “a couple of thousand pregnant women” have likely been exposed to lead-contaminated water. For pregnant women this means “a heightened risk of pre-term delivery, increased rates of miscarriage, and low birth weight in infants,” he said.

In fact, one of the earliest notices warning residents to refrain from drinking Flint water, back in September of 2015, was directed at “senior citizens, children, and pregnant women,” after an independent study by the Hurley Medical Center found double the acceptable levels of lead in Flint water.

But simply issuing such an advisory in a city with a staggering poverty rate could not ensure compliance. In its Geography of Poverty article series, MSNBC reported that between 2009 and 2013, nearly half (41.5 percent) of Flint’s residents lived below the poverty line, far higher than the state’s 16.8 percent poverty rate. During the same period, about a quarter of Flint’s families lived on less than $15,000 per year, while the child poverty rate was 66.5 percent—nearly 10 percentage points higher than Detroit’s, which sits about 70 miles south.

“When you live in the affected zip codes you don’t have a choice,” Dr. Hebert explained. “You can’t simply stop drinking the water. Mothers have used this water to prepare formula for their infants; they may have been forced to drink contaminated water and then breastfeed their children. This crisis is absolutely not to be taken lightly.”

“The Damage Has Already Been Done”

Reproductive justice advocates say the situation in Flint not only represents a local public health emergency but also mirrors a larger crisis of reproductive justice for low-income women of color around the country.

“We are seeing so many intersecting issues—from economic justice to environmental justice to health-care access—meeting right in the middle, and landing in a community that is overwhelmingly Black and where low-income communities of color are bearing the brunt of this collision in the most horrific ways,” Monica Simpson, executive director of SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, told Rewire. A majority of Flint’s residents—about 52 percent—are Black.

Simpson stated, “This is a severe reproductive justice crisis that cannot be ignored.”

Referring to the fact that Michigan’s Republican-led legislature, which was complicit in the water crisis, has a long history of pushing a so-called pro-life agenda, Simpson said, “This is our opportunity to reclaim our language. For too long many of us within the reproductive justice movement have been forced into the ‘pro-choice’ category by default, because we support abortion access. In fact, I consider myself pro-life: I support every woman’s right to live her best and most healthy life possible. But I haven’t been able to embrace that label, which has been hijacked by people who call themselves pro-life but are really pro-privilege and pro-white supremacy. If they cared about life, they would not be hand-picking who gets access to water, they would be ensuring that every woman and child has that right and that access.”

For reproductive health-care providers, the decision to respond to calls from the community was an obvious one. Planned Parenthood’s Boston told Rewire that the Flint Health Center, which sees about 3,200 patients annually, amounting to close to 7,000 visits each year, initially distributed water filters in partnership with the Flint Health Department, and later began to hand out free bottled water.

Flint resident Tunde Olaniran, the outreach manager for Planned Parenthood of Mid and South Michigan, who first brought the crisis to the organization’s attention, said he took his cue from local organizers who’ve been mobilizing since the switch happened back in April 2014.

“I was listening to the voices of women of color and organizations like the Genesee County Healthy Sexuality Coalition and the Coalition for Clean Water, who were talking about the toxicity of water long before any reports were released,” he told Rewire. “There is a lesson here on the need to listen … to grassroots organizers and impacted community members on how to solve very serious issues.”

Boston said that many patients and visitors to the center are “still expressing fears, confusion, and anger.”

“They are looking for guidance on what this means for their children, their families, and their own health,” she explained, adding that the clinic continues to educate patients about possible health risks and steps they can take to mitigate the impacts of lead contamination. Staff at the Flint center are urging women to “pump and dump” their breast milk, especially if they haven’t been tested; advising men on the possibility of lead contamination reducing their sperm count; and handing out resources, including lists of where testing is being done.

As residents fret over their health, the city is continuing to issue bills and past-due notices for water that residents say is good for nothing but flushing the toilet. The Detroit Free Press reported Monday that some 100 residents protested outside the Flint city hall, ripping up their bills—as high as $100—and holding signs reading, “Why Pay for Poison?” According to some sources, Flint residents are saddled with some of the highest water bills in the country, often touching $150 per month.

While the political machine continues to grind on—with groups like the ACLU now pushing for several reforms including the immediate repeal of Public Act 436, which enabled a string of politically appointed emergency managers to override public concerns about the water—health-care providers are preparing for the long haul.

“A lot of the damage has already been done,” Dr. Hebert told Rewire. “There is no magic anecdote that can reverse it. Cognitive deficits and other neurological impacts on infants and unborn children will not become apparent for a long time. We are not talking about weeks or months here—these children are going to have to be monitored closely for several years.”

He said there is an urgent need for thorough follow-through and early childhood intervention programs to give a boost to those kids that wind up with developmental difficulties.

And even these steps, some say, will not be enough. “I think the families and the women who have come forward and put this issue on the map are very brave,” Michigan Welfare Rights Organization’s Orduño said. “But I don’t see how there can ever really be adequate solutions, or recourse, or reparations for any of this.”