How Photographer Wendi Kent Hopes to Galvanize the Quiescent ‘Pro-Choice Majority’

While Kent’s photographs show predictable tableaux, they underscore the contradiction between protesters’ declarations of Christian compassion and their behaviors: yelling, shaming, and metaphorically bludgeoning people with the Bible.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

Photojournalist Wendi Kent avoids using the word “shoot” as she takes pictures at abortion clinics nationwide.

It’s such a common part of the photographer’s vocabulary that it’s hard not to say. But in light of clinic shootings like the recent one at a Colorado Planned Parenthood, the word takes on grim meaning and Kent steers away from it.

Kent, of Madison, Wisconsin, travels the country for her ongoing “Faces of the Fight” photojournalism project. It’s a distinctly different enterprise than other abortion-related photography or visual advocacy, which have tended to focus on rallies, specific political campaigns or measures, or on the stories of women who have had abortions, such as Allison Joyce’s “Abortion: After the Decision” or Jennifer Baumgardner’s groundbreaking “I Had An Abortion” campaign.

Kent takes pictures of anti-choice protesters who surround clinics often for the purpose of bombarding staff, patients, and passers-by with images of fetal remains and condemnation. Her photographs capture anti-abortion activists who hover and pray silently; others who throw dolls drenched in faux blood on the sidewalks where they “counsel” women; and vocal opponents who spout nonstop religious invective.

While Kent’s photographs show predictable tableaux—clinic escorts guiding patients, signs about the “unborn,” and prayer circles—they underscore the contradiction between protesters’ declarations of Christian compassion and their behaviors: yelling, shaming, and metaphorically bludgeoning people with the Bible. In a movement that proclaims that “all lives matter,” there’s no respect for the lives and livelihoods of women and families who choose abortion or the clinic staff.

The genesis of “Faces of the Fight” was in 2014 when Kent saw a “Wanted”-style poster with the names and pictures of reproductive rights journalist Robin Marty, writer-activist Katie Klabusich, and physician Cheryl Chastine. It was a chilling use of publicly available photography and an implicit threat. Abortion providers have been put on “hit lists” and such fliers have been plastered in the neighborhoods where they live and work. At least four physicians who provided abortions and were featured on similar posters were murdered, according to the Feminist Majority Foundation’s Clinic Access Project.

“I thought, ‘Who were these people protesting [against abortion at clinics]? And why don’t we know their faces?’” Kent told Rewire. Referring to information some providers and clinic employees have had recorded and published by abortion opponents, she asked, “Why don’t we know [protesters’] names, license plate numbers, and places of employment?”

“I’ve never seen any extensive photographic documentation of these protesters and their behaviors,” she added. “I decided that had to be remedied. In this day of social media, images are shared in a heartbeat. I thought that if some images back up [reports of anti-choice mobilization], people might be more inclined to pay attention.”

Still, Kent’s intent is not to “out” the anti-choice activists, provide legal evidence if they overstep, or give them a platform; she pointedly does not identify them. Instead, she hopes her photographs will galvanize what she calls the quiescent “pro-choice majority” of Americans who balk at the thought of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade but who take few steps to preserve it.

There’s no compelling evidence that abortion-related images can convert, activate, or move viewers in any particular direction, though it’s undeniable that fetal imagery has changed the stakes of the debate since such images from Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson appeared on the cover of Life magazine in 1965.

Yet Kent said: “I care too much about people to be idle. I don’t have formal training, a college degree, or a look that allows me to be in leadership roles. I have art and passion. I believe art moves people. And people move people.”

And she aspires to be a “people mover.” In July of 2015, she chained herself to a banister in the Wisconsin statehouse to protest the passage of a 20-week abortion ban—an action that made her one of the photographed rather than the eyes behind the lens. She also founded the Abortion Truth Project, which brings together community members for teach-ins with abortion providers and advocates.

But her activism has deeper roots. And protesters are partly right when they speculate that something personal has brought her to the clinic with camera in hand—though their conjectures usually take the form of hurled insults that she’s a “wicked woman” or jabs about her morality or marital status.

As a 13-year-old in Texas, Kent got pregnant. Her boyfriend at the time told her he wouldn’t love her if she had an abortion. Her father told her that she couldn’t continue to live with him if she had the child.

She tried to end her pregnancy herself, though she doesn’t go into details. “I stopped before I hurt myself,” she said. She delivered a baby girl, whom she eventually turned over to the birth father’s family.

“You’re on Public Property”

While out taking pictures, Kent arrives prepared for any situation, whether protesters are maintaining a safe distance between themselves and clinic visitors or are trying to engage women by following them to their cars. Her toolkit includes a camera, smartphone (she sometimes uses it to take pictures, but meticulously removes her private photographs in case it’s lost, stolen, or confiscated), and resources from the American Civil Liberties Union’s “Know Your Rights” guide for photographers.

She’s watchful because tempers can flare in an instant, especially when protesters come up against a stressed patient or companion who’s had enough. Kent keeps chatting to a minimum, rarely sharing personal information even with clinic escorts.

She’s just as careful to avoid sharing information about clinics or their patients. She does not show faces of women who seek services. Though Kent typically photographs outside, obtaining clinics’ permission to be on their grounds, she occasionally takes photographs inside them.

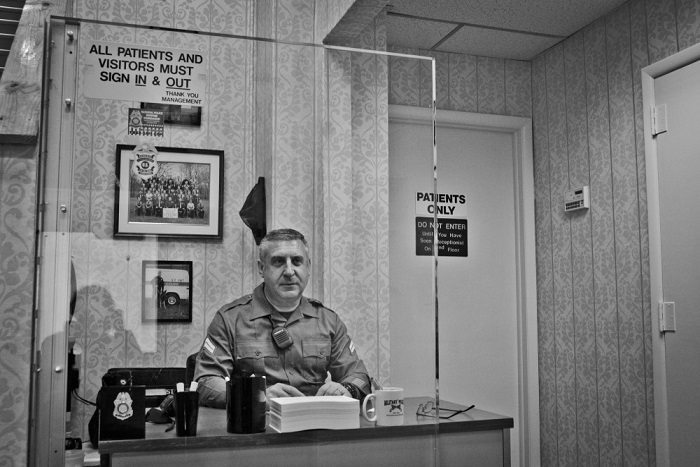

This image of a security guard ignited the curiosity of protesters at one clinic, according to Kent. One of the protesters questioned her about the facility’s layout, asking where women were sitting. When Kent asked why he was so intent on understanding the clinic’s design, he replied, “I wanted to know if the women could hear me” inside.

On a crisp winter Saturday in Raleigh, North Carolina, Kent moved between multiple spots around the A Woman’s Choice clinic. It’s a difficult place to photograph the protesters; patients have a separate entrance.

But it’s also a hard place for many of the women who come for abortions. Protesters have donned brightly colored vests like those of escorts, making it hard to determine who’s there to help patients enter the building and who’s there to talk about heaven and hell.

Parking is just far enough away from the entrance that patients have to walk by and through protesters, who station themselves in front of and just beyond the clinic. There’s also a hill where many protesters stand and shout from on high; sometimes, they stop individual patients to keep them from entering the clinic.

Kent’s presence did not go unnoticed. “A member [of Raleigh’s Upper Room Church, which has an active anti-choice ministry] came up to me. He’s really aggro and says ‘You’re in my personal space. Ma’am, ma’am, you can’t take pictures of us.’ I said, ‘Actually, I can. You’re on public property.’ A second person said, ‘We’ve called the cops on them before.’ I told them, ‘Look, you can take pictures of me, too,'” she explained.

While the protesters described Kent to the 9-1-1 operator, she clarified the color of her coat and chimed in with her name.

When the first of two cruisers arrived, Kent approached the older-model car and introduced herself to the officer, who rolled his window down an inch and barely spoke a word.

Not so the protesters. The mostly African-American group revved up whenever another Black person approached the vicinity. Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger was a frequent subject of their vitriol (though the clinic is not affiliated with the Planned Parenthood Federation of America).

When a young, Black man exited the clinic and accepted the company of pro-choice escorts, one of the group’s leaders heckled him.

“Young man, what is this? You need a middle-aged white woman to walk with you? How about you reverse those roles and walk out the woman you laid with?”