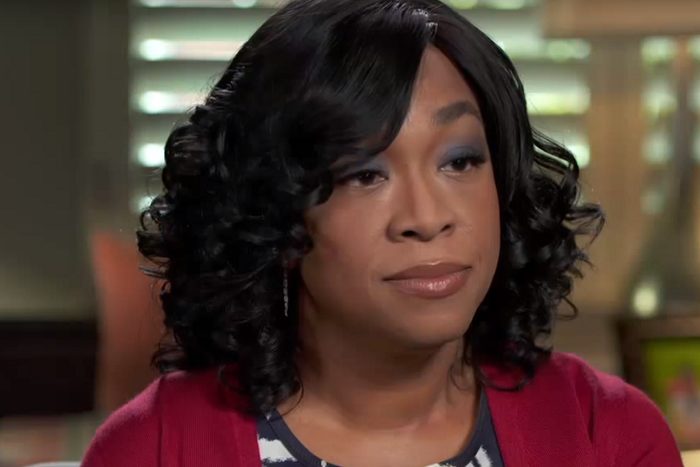

Abortion in ShondaLand: How the TV Producer Is Flipping the Script on Reproductive Health-Care Storytelling

From Grey's Anatomy to Scandal, Shonda Rhimes and her shows are pioneering how our popular culture represents abortion care.

On Thursday night, a Shonda Rhimes show once again created waves for a storyline about abortion. And it wasn’t just a passing political mention or a detail of a peripheral character’s history. It was a full episode of Scandal, with the show’s primary protagonist, Olivia Pope, getting her own abortion, paired with former First Lady Mellie Grant, now a junior United States senator, filibustering a spending bill in support of Planned Parenthood.

As there have been more and more abortion stories on television in the past few years, it’s important to recognize how groundbreaking Rhimes’ work truly has been. Rhimes is a board member of Planned Parenthood of Los Angeles, and is clearly invested in how abortion is portrayed in our popular entertainment. Indeed, her shows are unique in these portrayals.

Our Abortion Onscreen research at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health has found that a notable proportion of television characters face adverse outcomes after their abortions. Rhimes’ characters don’t. We found that 87 percent of characters seeking abortions are white. Rhimes’ aren’t. And we found the characters that provided abortions were all either one-time providers or peripheral characters. The only exception was Addison Montgomery from Rhimes’ shows Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice. While depicting abortion decision-making and provision is still somewhat novel in its own right, Rhimes is not only depicting it, but she’s depicting it in critically new, realistic ways.

Rhimes’ abortion stories have evolved, from Cristina Yang’s first abortion decision on Grey’s Anatomy to this week’s Scandal. In that early Grey’s Anatomy episode from 2005, the surgical intern planned an elective abortion only to discover that her pregnancy was ectopic and needed to be removed surgically. As Rhimes told TIME magazine, the plot twist “bugged [her] for years.” When Yang faced another unplanned pregnancy in 2011, she did get an elective abortion. The character, played by Sandra Oh, was determined and unapologetic about her abortion, and she directly challenged the commonly held idea that while abortion is often regrettable, parenthood never is.

Later, on the Grey’s Anatomy spin-off Private Practice, abortion would become a recurring theme. Obstetrician Addison Montgomery (played by Kate Walsh) was an abortion provider, and proud to be. In one episode, she passionately proclaimed, “It is not enough just to have an opinion, because in a nation of over 300 million people, there are only 1,700 abortion providers. And I’m one of them.” This was a personal and political statement, acknowledging Montgomery’s commitment to providing abortions and recognizing the scarcity of providers in the United States. Montgomery also defended another doctor’s right to perform abortions within their practice, continually challenged her anti-choice colleague’s stance, and repeatedly mentioned anti-abortion violence and barriers to care. Beyond that, she disclosed her own history with abortion—and she was not the only physician on Private Practice to do so. On both Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice, the lines blurred between those providing abortion care and those in need of it, showing viewers that women of all backgrounds face such decisions.

But Scandal has broken barriers that even these previous Rhimes shows did not. In an episode last May, character Olivia Pope (Kerry Washington) helped a young naval officer have an abortion after a sexual assault. In this storyline, viewers watched the abortion on-screen. Viewers saw the doctor’s hand turn the aspirator on, and the patient’s face and the doctor’s back during the procedure.

This was new territory. With few exceptions, previous abortion storylines—on Rhimes’ shows, and elsewhere—had almost always cut away as the procedure was about to begin. (The exceptions seemed to be ectopic pregnancy removals: Yang’s surgery was shown, as was a similar surgery on House. Interestingly, in both of these surgeries, the women intended to have elective terminations before they knew they had extrauterine pregnancies. However, on both of these medical shows, which featured other elective terminations, the procedures happened off-screen.) But Scandal showed the abortion directly—and it did again last week. In fact, the Scandal abortion scene depicted even more detail, showing the doctor at work. The doctor inserts the curette and the vacuum aspirator; then the viewer sees the doctor’s arm moving deliberately. Through her shows, Rhimes seems to represent the final veil on abortion care, putting the actual procedure on primetime network television.

In the accompanying filibuster plotline, Rhimes flips the script on reproductive health-care storytelling in two ways: She has a highly visible Republican senator filibustering and shutting down the Senate in support of Planned Parenthood, rather than in opposition to it. This suggests that support for reproductive health care should be a bipartisan issue, and that progressive values could, perhaps, be as dramatically showcased on the national level in a way viewers of the show have not yet seen in real life.

None of this is to say that these shows portrayed abortion without reflecting our culture’s stigma. Montgomery described abortion as “the most difficult and personal decision that there is.” On another occasion, before performing a second-trimester procedure, she said: “I hate what I’m about to do.” These lines communicate that abortion is hard and heartbreaking, while for many women it is not. On last week’s Scandal, Vice President Susan Ross used the talking point in the debate on the Senate floor that abortion “only makes up 3 percent of all Planned Parenthood business.” This fact, while true, stigmatizes and marginalizes abortion within other reproductive health care, suggesting that it is less appropriate than Planned Parenthood’s other services. Additionally, it promotes the “safe, legal, and rare” argument that abortion should only happen in a narrow set of specific circumstances deemed acceptable by others.

Furthermore, Rhimes’ depictions aren’t always the most realistic. Pope gets her abortion at an ambulatory surgical center (instead of an abortion clinic, where 70 percent of abortions are performed, according to the Guttmacher Institute), and the details such as Pope’s hairnet or the surgical lights seem to visually imply that an ASC setting is the expected standard for abortion care. Indeed, portraying the scene in such a way might convey to viewers that ASCs are necessary and appropriate for abortion care, ceding ground to aggressive anti-choice measures that force clinics to needlessly comply to ASC standards, which professional health networks have argued are not medically necessary.

Ultimately, though, it seems that Rhimes’ on-screen abortion stories do more work contesting abortion stigma than producing it. Last Thursday, on network primetime television, over eight million viewers watched a Republican senator and a vice president theatrically stand up for Planned Parenthood. They watched a woman of color have an abortion, and they saw a depiction of an abortion procedure. They saw Olivia Pope do this, without fear, without hesitation. Shonda Rhimes and her shows are pioneering how our popular culture represents abortion care—and these shows aren’t going away anytime soon. It remains to be seen which taboos she’ll break next.