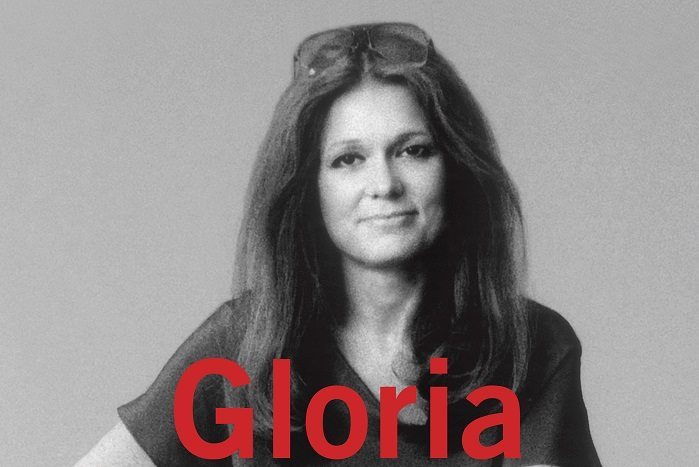

For Gloria Steinem, Adventure Lies ‘Just Beyond an Open Door’

My Life on the Road is part autobiography, part political treatise, and part impressionist account of the amazing people and places Gloria Steinem has encountered during the four-plus decades she’s been an itinerant feminist agitator.

When I was 14, activists Gloria Steinem and Florynce Kennedy came to a synagogue in my hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, to give a talk about the then-burgeoning women’s movement. It was the late 1960s, and feminism had begun to ignite wide-scale interest in the struggle they championed. The room was packed to bursting and I recall the thrill of hearing Kennedy pepper her presentation with the word “fuck.” What’s more, I remember the pair’s passion and wit, and left the auditorium feeling excited about the possibility of winning gender equality.

I became a quick convert to what was then known as women’s liberation. Secondarily, I hoped that my life would be as exciting and glamorous as I imagined Steinem and Kennedy’s to be.

Needless to say, I was not unique in this resolution. Indeed, Steinem and Kennedy’s energy was contagious and their presentations undoubtedly influenced audiences around the country—adults as well as teenagers—to envision a more egalitarian world. But Steinem’s latest memoir, My Life on the Road, out today from Random House, does not strongly detail the effects of her activism. Instead, the book is part autobiography, part political treatise, and part impressionist account of the amazing people and places she’s encountered during the four-plus decades she’s been an itinerant feminist agitator. It’s a fascinating gallop through her early years, touching upon her political awakening and campaign involvements as well as the creation of Ms. magazine and the National Women’s Political Caucus. Along the way, she introduces a cast of memorable characters, from cab drivers to congresspeople.

The result is an intensely moving, humble reflection on a remarkable life.

“When people ask me why I still have hope and energy after all these years, I always say, ‘Because I travel,’” she writes in the book’s introduction. In speeches on college campuses and in coffee shops, religious institutions, and community centers, Steinem writes that she not only talks, but listens. “What we’re told about this country is way too limited by generalities, sound bites, and even the supposedly enlightened idea that there are two sides to every question,” she writes. “In fact, many questions have three or seven or a dozen sides.”

Investigating these nuances has motivated Steinem to spend more than half of her adult life traveling, lecturing, and seeking input from Americans throughout the 50 states. Yet there is more to the story. In addition to wanting to spread feminist ideas and ideals, Steinem confesses that there is a far more personal reason for her wanderlust: a psychological longing for movement that mirrors the desires of her larger-than-life father. Leo Steinem “wanted no home at all,” she says, and was content to live out of his car, or in cheap motel rooms, doing a little of this and a little of that to keep himself, his wife, and his two daughters minimally fed and clothed. Steinem’s love for her adventurous dad is obvious, and her early childhood years are, for the most part, presented as pleasant. At the same time, Steinem admits that there were times when she longed for a more stable upbringing, with a school she could walk to and friends and family who lived nearby.

When Steinem was 10, she got her wish. Her parents separated, and she began to live with her mother full-time, first in Massachusetts and then in Ohio. Unfortunately, being settled was not as she’d imagined. Her mother suffered from severe depression and when Steinem was a teenager her mother’s illness prompted her to move to Washington, D.C., to live with her older sister. College, and then a two-year fellowship in India, followed.

Steinem recounts time spent in the ashram of Vinoba Bhave, the leader of an Indian land reform movement, as particularly instructive. Bhave and a team of supporters, including Steinem, walked from village to village, requesting that landowners give a small percentage of their property to the landless. Their methods involved community discussions using a technique that was new to Steinem: the talking circle. “It was the first time I witnessed the ancient and modern magic of groups in which anyone may speak in turn, everyone must listen, and consensus is more important than time. I had no idea that such talking circles had been a common form of governance in most of human history, from the Kwei and San in southern Africa, the ancestors of us all, to the First Nations on my own continent, where layers of such circles turned into the Iroquois Confederacy, the oldest continuous democracy in the world.”

The experience further taught her some organizing basics: “If you want people to listen to you, you have to listen to them. If you hope people will change how they live, you have to know how they live. If you want people to see you, you have to sit down with them eye-to-eye.”

By the time Steinem returned to the United States in the early 1960s, the civil rights movement was in full flower and she credits the 1964 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom with pushing her to get involved in domestic politics—and feminism. She writes that during the march she found herself standing next to a woman named Mrs. Greene, whose first name she does not include, a Black woman who had worked in a segregated D.C. office during the Truman administration. This indignity was not the only thing that rankled Greene and she grumbled that only one woman, Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women, was on the dais, and none had been asked to speak to the assembled crowds.

“I hadn’t even noticed the absence of women speakers,” Steinem says, nor had she “thought about the racist reason for controlling women’s bodies.” Still, she writes, “I felt a gear click into place in my mind … Thanks to Mrs. Greene—and many others brave enough to stand up for themselves and other women—I began to understand that females were an out-group.”

Eventually, under the tutelage of Dorothy Pitman Hughes—a now 77-year-old pioneer of nonsexist, multiracial child care, a co-founder of Ms. Magazine, and the woman credited with organizing the first shelter for battered women in New York City—Steinem harnessed her fear of public speaking and, with Hughes, began her career as a spokesperson for the emerging feminist movement. “Since we had been successful one on one, Dorothy suggested we speak to audiences as a team. Then we could each talk about our different but parallel experiences, and she could take over if I froze or flagged,” she writes.

Utilizing the talking circle she’d seen in India, she and Hughes helped audiences of women and men of all races and social classes “discover they were neither crazy nor alone in their experiences of unfairness or efforts to be both their unique selves and to find a community,” noting that their attendees “told their own stories.” That said, not everyone was overjoyed with the duo’s message—or that of her later pairing with Florynce Kennedy, who died in 2000—and Steinem reports that on one hand, she was berated by the press as too attractive to be a feminist, and simultaneously called a lesbian, a presumed insult. “I learned to just say, ‘thank you,’” to the insinuation, she writes. “It disclosed nothing, confused the accuser, conveyed solidarity with women who were lesbians, and made the audience laugh.”

Meanwhile, Steinem continued to be in demand as a speaker. Rather than driving in a car alone, she reports that she almost always used public means and includes numerous anecdotes about her encounters with cab drivers and passengers on trains, buses, and planes; all add to the book’s charm.

Similarly, her account of her decades-long friendship with Wilma Mankiller, chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1985 to 1995, is tender and filled with affection and humor. Her account of Mankiller’s 2010 death, surrounded by Steinem and other loved ones, is also a model for dying with dignity.

All told, most of Steinem’s stories accentuate the positive, and showcase people’s goodness rather than their avarice or malice. Nonetheless, one negative tale zeroes in on author/activist Betty Friedan’s unsuccessful bid to take the helm of the National Women’s Political Caucus at its founding convention in 1971. The way Steinem tells it, Friedan’s arrogance and the lack of supporting sisterhood is appalling. This, however, is an exception in an otherwise upbeat account of Steinem’s work as a feminist community organizer and writer.

There is, however, one glaring omission: Her three-year marriage, which lasted from 2000 until her spouse died in 2003, is never mentioned, leaving me to wonder how she juggled so much travel with maintaining the relationship, or if this was an issue. I also wanted to know if she ever got tired of being on the move.

Although neither topic is tackled, Steinem does write that after she turned 50—years before her marriage at age 66—she began to crave a place of respite and finally took steps to create a comfortable nest to return to when she was not on the road. This, she stresses, did not diminish her enjoyment of travel. It did have an impact though: “I lost the melancholy feeling of Everybody has a home but me. I could leave—because I could return. I could return—because I knew adventure lay just beyond an open door. Instead of either/or I discovered a whole world of and.”

Steinem is now 81 and seems unlikely to retire from writing or speaking anytime soon. My 14-year-old self was right to see her as a role model and My Life on the Road reminded me how pithy and insightful she continues to be. Indeed, she not only provokes optimism about egalitarian possibilities, she inspires new generations to want more and better. She deserves our respect and gratitude.