Celebrating Baltimore and Black Ebullience

The plight of the Black community, in Baltimore and elsewhere, should not overshadow the vibrancy and resilience of Black people.

When I told my family I was moving from my hometown in New Jersey to Maryland a year ago, the first (and only) question asked was how close I would be to Baltimore. They did not ask out of sheer curiosity. They asked because they, like many others, see Baltimore as a place to avoid.

But if there’s one thing the Ferguson Uprising has taught me over the past year, it’s that the worst thing we as a society can do is avoid racially segregated communities like those in Baltimore. While poor communities often have higher arrest rates (which as we know is a result of the over-policing of the poor more than it is a result of any particular racial group being more prone to violence than others), they also have an unprecedented sense of community and culture that is oftentimes ignored by those unwilling to see impoverished neighborhoods as anything but dangerous.

Helping these cities thrive requires us as a society to change as well: We must begin to recognize it’s not just rich, white people who make the country prosper. So even as advocates work to eliminate systemic injustices, we—all of us—must also celebrate the life and culture of the Black community, in Baltimore and elsewhere. The plight of the Black community should not overshadow the vibrancy and resilience of Black people.

A long struggle of racial discrimination not only created the state Baltimore is in, but also spawned the Black Lives Matter movement, which works to thwart it and white supremacy writ large. Avoiding the city altogether is an act of erasing that struggle. As Greg Howard states at The Concourse, systemic racism is the reason for segregated neighborhoods and schools, for corrupt policies like redlining, and for the large wage gap between Black and white people. The Black community in Baltimore grew exponentially during the Great Migration and started to enter historically white neighborhoods. In response to that, white Baltimoreans fled (otherwise known as “white flight”) and took their businesses, their jobs, and their money with them. Shady tactics like redlining were implemented to keep Black individuals from progressing or even living near well-resourced communities. So when we talk about the problems with Baltimore, we’re not just talking about Baltimore today, but a Baltimore that is decades-old.

But Baltimore is more than its tough times. I had to learn this past year, since Michael Brown’s death, that declaring “Black lives matter” means more than mourning the loss of another person, but celebrating the beauty of Black people and our culture. I realized that I had only been mourning the loss of Black people in the last twelve months, as each month brought another reason to protest, another Black body downed, when I stepped foot into the heart of Baltimore during its annual art festival, Artscape.

Artscape is the largest free art festival in the United States, according to its website. More than 350,000 people attended this year’s event, Tracy Baskerville, communications director for the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Arts, told me in an email. The three-day event celebrates art in all forms, from video games to interpretive dance, and encompasses the unique culture that is Baltimore. It is a multicultural event meant to represent diversity living within Baltimore. The audience and artists involved come from a variety of different backgrounds. Artscape does not specifically focus on Black art and culture (though Baltimore does have an event specifically for that), but personally, I couldn’t help but pay close attention to the Black people, both artists and attendees, who seemed to be well-represented there.

Inspired by the Baltimore City Fair, which was created two years after the Baltimore Riots of 1968, Artscape started in 1982 as a way for Baltimore’s residents to celebrate the region’s burgeoning art scene.

In 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Baltimore residents, as well as residents in hundreds of other cities across the country, rioted as soon as the news broke. Though the protests began peacefully on April 4, arson and looting did follow in Baltimore, and lasted for an entire week. As assistant professor at the University of Baltimore, Elizabeth M. Nix, stated in Slate, the Baltimore Riots changed the perception of the region for those living outside of it, who were not aware of the rising tensions facing Black individuals in these communities. During this period, Baltimore gained notoriety for its rioting and destruction. This is why some people outside of Baltimore, or cities like it, have maintained a “stay away” mentality, without questioning the reasons for that destruction.

Unfortunately, people flocked again to stereotypes about area residents during this year’s protests following the death of Baltimore resident Freddie Gray. Gray died in April while in police custody after suffering severe spinal injury, for which the officers failed to get him needed medical treatment in a timely fashion. During the protests against racist police violence, the media coverage appeared to focus more on a burning CVS than Baltimore’s racially charged history that spurred the citywide actions.

Back in 1970, then-mayor Thomas J. D’Alesandro III created the Baltimore City Fair to raise awareness of the richness of Baltimore. After the Baltimore riots, a large population of white citizens moved out of the city. But despite the region’s misfortunes, Mayor D’Alesandro wanted to show Baltimoreans they still had a reason to come downtown.

I saw Artscape last month as a similar symbol of hope for the city. This year was my first time going, and while I can’t speak for the previous years, this one felt necessary for the city. It was a way to show those who solely believe in stereotypes that Baltimore is, and always has been, more than its hardships.

As much as the weekend-long festival was meant to bring joy to the city, parts of the festival delved into the movement. Actors from the Baltimore-based police drama The Wire took the stage for an event called “Wired Up! A Celebration of the Spirit and Power of the People of Baltimore.” The production paired actors with real-life activists, who were present during Baltimore’s riots, to share real stories from Baltimore citizens who experienced protests first hand, and who helped clean up the city after the crowds and news crews were gone.

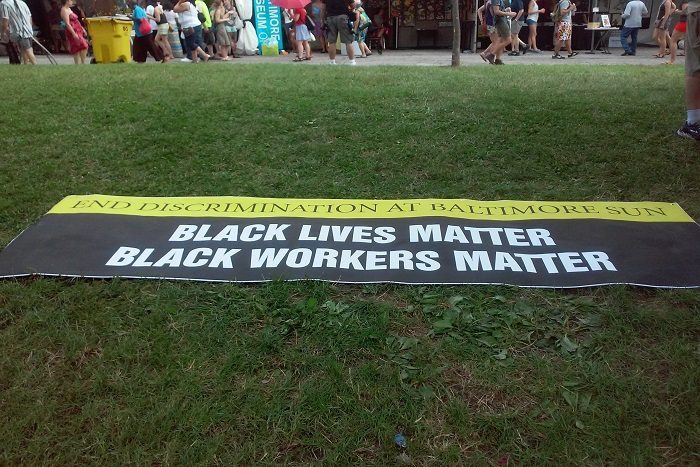

There was also a small protest at the festival against the Baltimore Sun, during which activists claimed that the publication initiated a discriminatory wage scale for mailer employees. Bottom-tier workers, who are predominantly Black, are paid less than top-tier workers who do the same job, according to the individuals handing out flyers. The protesters had a poster lying in the grass that said, “Black Workers Matter.”

I also saw at the art festival Black artists selling and promoting their work and Black children dancing and playing games. I saw happiness in Baltimore many think does not exist.

This isn’t to say that Artscape, or any festival, can heal all wounds plaguing Baltimore’s residents. Still, art inspires change, and supporting Black creativity is another way of saying Black lives matter—as we saw during the Harlem Renaissance, when Black artists were demanding space and recognition for their talent.

Put another way, acknowledging that Black lives matter is more than just mourning our losses; the movement will not disappear once the country has outlawed excessive and racially charged force. And it is more than forcing politicians to say the word “Black lives matter” without hesitation. To acknowledge the importance of Black lives is to celebrate Black contributions to our society in whatever form it takes, including Black labor and art. Baltimore and Black people should not be stereotyped because of hardships, but praised for the dedicated work we do in spite of the obstacles that try to oppress us.