Beyond the Coat Hanger: What’s Next for Abortion Rights Iconography?

For me, and many others born after Roe v. Wade, the fixation on coat hangers as the prevailing imagery of the reproductive rights movement excludes the possibility of alternatives that are more relevant to current struggles.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

For many in the reproductive rights movement, the coat hanger is more than a commonplace closet item. Activists use it to memorialize those girls and women who turned to unsafe abortions out of desperation when abortion was illegal. It transforms into shorthand for “Never again.”

Although the symbol resurfaces throughout the year, it becomes a frequent sight around the January anniversary of Roe v. Wade. As I saw coat hanger references earlier this year, I felt an odd dissonance. I knew what I was supposed to feel: outrage, sadness, and a renewed commitment to reproductive justice. Instead, though, I only felt unmoved and then unnerved. For me, and many others born after Roe, the fixation on coat hangers as the prevailing iconography of the reproductive rights movement excludes the possibility of alternatives that are more relevant to current struggles.

Part of my discomfort was rooted in historical quibbles; while the coat hanger is the enduring symbol of women’s determination and desperation to end pregnancies during the era of illegal abortion, the implements of pregnancy termination also included catheters, toothpicks, unnaturally long fingernails, and drugs—even well before medication abortion was an accepted practice. And as durable as the images of the coat hanger or dangerous back-alley procedure may be, not all illegal abortions were unsafe; many were performed by trained clinicians working outside the law. In addition, as part of the first post-Roe generation, I didn’t live through a time when many hospitals had so-called “dirty” wards, where they treated women suffering from botched abortions. As much I hate to admit it, the coat hanger doesn’t resonate with me or many other people my age or younger.

Given these realities, combined with the abortion storytelling trend—through which women publicly share their experiences with reproductive care—it is surprising that more advocates in the mainstream movement have not honed in on visual storytelling’s potential to change the way the general public perceives our issues. Considering, for example, the remarkable artistic flowering and public visual commemorations (such as “hands up” pictures) that are part of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it’s time for the reproductive rights movement to get on board too.

Because images matter. Even if we stop short of agreeing with the old adage that “seeing is believing,” they can still influence, inflame, and reinforce beliefs—and we should be taking advantage of that.

Some activists have begun to pinpoint the problems with the movement’s existing iconography and to propose and create alternatives. Boston-based artist Megan Smith, who created the Repeal Hyde Art Project to increase dialogue about the federal policy that restricts Medicaid funds from being used to support abortion care except in case of rape or incest, points out that the coat hanger, on its own, reduces the struggle for reproductive health-care access to a single act of danger.

“Perhaps the coat hanger does what it’s intended to do. It makes me uncomfortable and makes me think about the violence [inherent in restricting women’s rights],” Smith told Rewire. Through art, she said, “I want to find a way to honor that history, what illegal abortion meant, and be respectful of what that means for people who have that real connection to that history. But I don’t know if that’s the message to put out there and for people to share. Women are resilient. Where are the images of resilience? Where are the images of faith? Where are the images of optimism?”

This narrow scope, she noted, reflects activists’ frequent embrace of narratives of suffering when garnering support for reproductive rights. “When talking about abortion access, we tend to victimize women who can’t afford their abortions or don’t get them. We are not opening the narrative to talk about women who have overcome that,” she said.

Still, it is challenging to convey the wide range of reproductive health experiences in a lasting, recognizable way. When Smith first began thinking about reproductive rights and visual media, she observed the limited repertoire already in use: the astrological female symbol, a silhouette of the uterus (not exactly familiar without a more-than-basic knowledge of anatomy), or the raised fist popularized by Black nationalists. She wanted to use art to give people an entry point to talk about abortion and reproductive rights without either contributing to the existing echo chamber or veering automatically to the polemical. To that end, her installations feature paper birds—whose flight, she says, can symbolize transcending the abortion debate. She invites spectators to add their own winged creation; often, passersby become participants just because they are drawn to the flock of simple, origami-like creatures.

Graphic designer Andrea Goetschius, also of Massachusetts, has had similar struggles in her work with international women’s health organizations. Too often in mainstream symbolism, she tells Rewire, pregnant women are reduced to nothing but body parts. This issue, she says, extends to general messaging about reproductive health.

“This isn’t just a problem about abortion; it’s a problem in terms of [illustrating] the spectrum of reproduction. If you try to find any image of pregnancy, you get ultrasounds, and you get bellies without heads. And these are white bellies. I refuse to use disembodied women,” she said. Instead, she frequently works creatively with fonts or typography rather than use pictures: “I’ve often chosen to strip the images … because it’s worse to perpetuate the de-centering of the woman.”

Maggie MacDonald, a visual anthropologist at York University in Toronto, has a slightly different take. She agrees that depictions of women are now largely absent from global reproductive health groups, especially those aiming to reduce pregnancy-related deaths worldwide. However, she notes, those campaigns have instead adopted pre-adolescent girls as their poster children, often pictured in school clothes or skipping in the sunlight.

This hypothetical young girl, MacDonald said, allows global information consumers to experience a “shared sense of humanity, through hope and aspiration. We want her to delay marriage, stay in school, use contraceptives, space her children.” But depicting schoolgirls as the ultimate target of reproductive health services strikes MacDonald as irresponsible, in that it ignores adult women’s needs and wants.

However, focusing on adult women should not mean the exclusion of offspring altogether; in an effort to center women, other reproductive health organizations that specifically work on abortion hesitate to use pictures of children in their publications. That is also short-sighted, says Madison, Wisconsin-based graphic designer Heather Ault.

“I think that’s the wrong approach,” she told Rewire. “Abortion is ultimately about motherhood, and women who are mothers are the majority of those who are having abortions. I think that by ignoring that fact, we’re missing out on an opportunity to tell the story of motherhood. The idea that abortion is about motherhood—abortion providers talk about abortion that way, but our mainstream movement does not.”

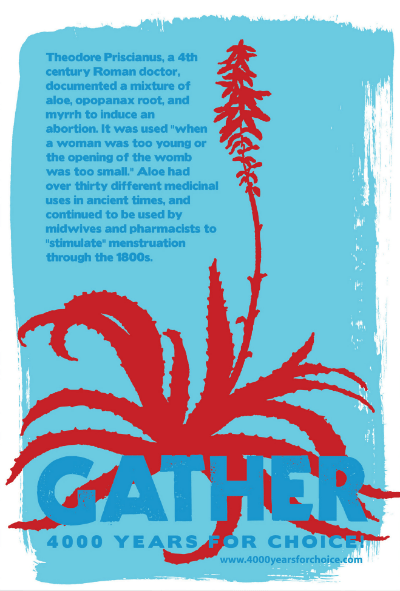

Ault is well known for her “4000 Years for Choice” exhibits, which tell the stories of abortion activism, contraceptive methods, and abortion procedures over time; she’s also produced some of the mostly widely circulated memes about reproductive health.

When preparing for “4000 Years for Choice,” Ault noticed that one political group in particular has consistently cogent messaging about reproductive issues: the anti-choice movement.

“In 2008, I went to the pro-life march in Washington, D.C. I marched with them, went to workshops. I felt like their signs were good. Their t-shirts were really good; there were so many different pro-life t-shirts you could buy. Almost any design, any personality. I was really impressed. I don’t agree with them, but they knew what they were doing. It was really inspiring from a design side,” she said.

In her view, abortion opponents were and are ahead of the game, designing apparel and billboards that put their messages on American streets.

Granted, it may be that the other side has an inherently simpler message. As Smith pointed out, “It’s not exactly nuanced: Abortion kills. That’s it.”

While that overarching message may be a great anti-abortion unifier, though, abortion opponents aren’t afraid to go for the gusto, trotting out images that may mobilize or even risk offending potential allies: notably, the bloody fetus. Since the invention and consumerization of the ultrasound, the fetus has taken center stage. It seems to float in “space,” independent of the person to whom it’s literally tied. She disappears or is only acknowledged as the fetus’ adversary—reinforcing her sublimation to the fetus in anti-choicers’ rhetoric and legislation.

Abortion rights activists may have a harder job in creating a symbolic language. How do you convey the state of abortion access—legal but increasingly restricted—visually? No single symbol can carry the weight of the many messages that emanate from these movements: obstacles, lack of access to contraceptives, women’s empowerment, abortion as a moral choice, and so on.

Goetschius says that reinventing a compelling visual language may force the reproductive rights movement to focus on targeting their audiences’ sympathetic as well as logical sides.

“Do we fall into the trap of trying to intellectualize this and not going for the emotional appeal? If we’re going for the equivalent of the cute baby”—the anti-abortion mascot—”why don’t we show happy and fulfilled women and men?” she asked.

But she does think that research can help determine new frontiers in the iconography of abortion rights; she hopes to one day run focus groups that ask women who have given birth or had abortions to draw their experiences, and to use their responses to generate new images. Similarly, she supports the idea of campaigns to submit and upload better images—say, those that show whole women and not merely their pregnant abdomens—to stock photography sites, frequently used by media outlets and ad companies.

For her part, Ault is waiting for the reproductive rights movement to invest money and time in finding new symbols. That may take a while because, as scholar Rosalind Petchesky wrote in a seminal 1987 article about the fetal image and visual culture, even feminists and pro-choice advocates find it hard to imagine positive images of abortion; we, she argued, “have all too readily ceded the visual terrain.”

To this end, the reproductive rights movement can take a page from the corporate and design worlds. Any new consumer product comes with a branding package that’s not just about the text. It’s also about the look: how evocative it is and how it aligns with the message.

When Ault started the “4000 Years” exhibit, she was surprised that something like it “hadn’t been done before—despite the fact that the feminist movement had been in full swing for decades. We’re an image culture, but our movement has been focused on state and national politics.” That focus, she says, means there are few artists like the Bay Area’s Favianna Rodriguez, who can build artistic reputations and movements at the same time.

“What would have happened if more than 40 years ago, our movement started funding ten different artists a year to do work about reproductive justice and funded spaces to show it?” she wondered. “If that had been a priority, we would have so many images we wouldn’t know what to do with them.”