Bill Cosby’s Alleged Assaults Hurt More Than Our Feelings

Media coverage of Bill Cosby's alleged assaults has portrayed the public's affection for him as the major casualty. But we should be focusing on the women who say they were attacked—and on the rape culture that concealed his reported behavior for years.

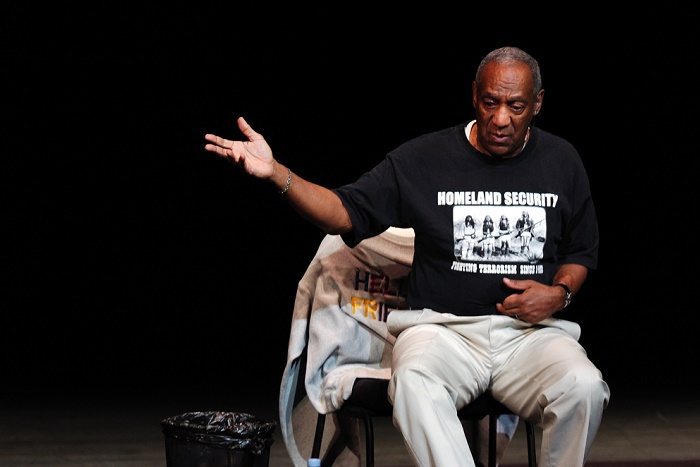

“You raped women, Bill Cosby.” With five words at an October 16 performance, stand-up comedian Hannibal Buress unwittingly reignited public discussion of allegations that Cosby had raped or assaulted multiple women. But rather than focusing on the women who say they were attacked, discussion has centered on the public’s affection for Cosby as the major casualty of his alleged behavior. Furthermore, the mainstream media has framed collective amnesia over these accusations as an exceptional phenomenon, an effect of Cosby’s wealth, fame, and iconic status—rather than putting the lackluster public response in the broader context of rape culture, or the intersections of gender, power, and violence in American society at large.

Until Hannibal Buress’ bit a month and a half ago, the biggest news about Cosby this year had been his planned comeback. Since the clip of his October show in Philadelphia went viral, however, at least 21 women have stated that Cosby assaulted or raped them, in many cases after drugging them as well. Cosby’s comeback has fallen apart: NBC scuttled his planned sitcom; Netflix indefinitely postponed his special, set to debut over the Thanksgiving holiday; and a growing number of venues have canceled shows originally set up as part of Cosby’s current national tour. The University of Massachusetts Amherst, where Cosby earned master’s and doctoral degrees in education, has cut ties with Cosby and asked him to step down as honorary co-chairman of its fundraising campaign. On Monday, Cosby resigned from his position on Temple University’s Board of Trustees. Virtually overnight, Cosby’s brand has gone from what Buress aptly called “teflon” to toxic.

Recent headlines tell the story of a nation collectively grappling with the rediscovery that a huge gulf may exist between Cosby the icon and Cosby the man. Such coverage has largely focused on the public dismay over having to reevaluate Cosby, and the question of why it took almost a decade—and a man calling Bill Cosby a rapist, as Barbara Bowman poignantly observed—for the country to take these allegations seriously.

“The Bill Cosby Myth,” columnist Margaret Carlson declared on BloombergView, “Is Dead.” Another headline, from the Associated Press: “Bill Cosby’s image as generous philanthropist falls under shadow of sexual assault allegations.” Grantland’s Rembert Browne and Wesley Morris devoted a lengthy exchange to “Processing the Fall of an Icon,” while at the San Francisco Chronicle, Mark Morford offered suggestions on “what you can do” about the “disgrace of Bill Cosby.” In typical breathless fashion, BuzzFeed promised to deliver “18 Moments That Led to Bill Cosby’s Stunning Downfall.”

Feeling bewilderment and disappointment in this moment is understandable. Bill Cosby was—still is—idolized not only in his country, but around the world. (Long before my family emigrated to the United States from Nigeria in the early ’90s, we tuned in religiously to watch the Huxtables and Hillman College’s motley crew.) That the creator of such well-known and beloved characters is capable of such horrific violence and duplicity is a genuine shock; there’s nothing inherently wrong with that.

Taken individually, there are legitimate reasons to write and publish a piece acknowledging the personal investment many of us have in the question of who, exactly, Bill Cosby is. But as reflections on Cosby’s “downfall” or broken legacy pile up, the resulting picture is one in which the irreparable tarnishing of Cosby’s image has become the moral and emotional center of the story. The “tragedy,” these articles suggest, is less that at least 20 women, by their account, had their bodies and their trust violated by Bill Cosby, or that they had nowhere to turn for help or support. Apparently, the tragedy is more that Bill Cosby may turn out to not be the ideal he sold us. The tragedy is that seriously considering the possibility that Bill Cosby is a serial rapist makes us feel sad and let down. The tragedy is that we, ourselves, have been betrayed.

In this telling, it is not the women who have risked so much to tell their stories who are the primary victims of Bill Cosby; it is the American public. It frames the fact that these allegations force us to consider Cosby in a new light as more distressing than suffering and living with the aftermath of sexual violence—for decades, in some cases.

Such rhetoric makes it clear that we are unwilling, as a culture, to reconcile the good we see in others, real or perceived, with the capacity for severe, sustained violence. When confronted with evidence that compels us to look beyond public veneers of or our individual experiences with our idols, role models, or loved ones, we process this as a betrayal, a wound, or as something done to us—often losing perspective of the people directly harmed.

Janice Dickinson has described years of a “vicious cycle of guilt, escape, bad choices” as the fallout of Cosby’s alleged violence. Bowman has said being “accused … of making the story up” by a lawyer “crushed any hope I had of getting help … That feeling of futility is what ultimately kept me from going to the police.” We do not primarily empathize with the perspectives of women like Dickinson and Bowman who have come forward. Rather, we routinely dwell on how allegations of sexual violence make us feel as people not harmed directly by the named perpetrator. This contributes to a culture in which rape is not discussed with the gravity, thoughtfulness, or nuance that it merits. And in turn, this is part and parcel of how rape culture makes it so difficult for survivors to speak out, or to be believed.

The inordinate focus on the myth of Bill Cosby also explains why media attempts to explore the extremely delayed impact of these allegations have fallen short: The focus on his fame and success overshadows the fact that his reported actions are similar to those of rapists who do not have his connections or influence.

Starting largely with Andrea Constand’s assault lawsuit, which was settled out of court in 2006, many of the claims against Cosby have been public for almost a decade; they have been a Google search away for anyone who cared to find them. Yet, Hannibal Buress noted in his fateful Philadelphia show that in his previous performances of “this [Cosby] bit … people don’t believe—people think I’m making it up.” In a widely shared piece for The New Republic, Rebecca Traister made a similar observation about how thoroughly the allegations against Cosby had been erased from public consciousness: “None of my students, a racially diverse group of women and men in their 20s and 30s, had ever heard about the sexual assault charges.”

One reason for this widespread ignorance was sparse coverage of Cosby’s alleged crimes during and after Constand’s lawsuit. As the Washington Post’s Paul Farhi wrote, for nine years the “story lingered at the fringes, fitfully reported. Soon enough, it went away altogether.”

This time around, the timing was particularly right for news about Cosby to go viral. Cosby’s PR machine was gearing back up for his comeback, making him topical for the first time in years. The same week that saw networks abuzz about Cosby, similarly viral allegations emerged of physical and sexual abuse by Jian Ghomeshi, a popular Canadian radio host with a high national profile and homey charm similar to Cosby’s. And as Farhi pointed out, the media landscape has changed: In the mid-2000s, the social media networks that helped to publicize and amplify the outrage against Cosby and Ghomeshi were just starting out. Furthermore, many outlets displayed a reluctance to report on rape allegations at all.

In addition to explanations of the transformed news machine, a consensus also seems to have emerged among media commentators that Cosby’s cultural significance as a paragon of respectable Blackness made Americans reluctant to acknowledge his alleged victims. Traister wrote, “We have collectively plugged our ears against a decade of dismal revelations about Bill Cosby…[because] he made lots of Americans feel good about two things we rarely have reason to feel good about: race and gender.” The Cosby Show, she continues, particularly appealed to white audiences by glossing over inconvenient truths of systemic white privilege and racial inequity. To accept that Bill Cosby could be a serial rapist meant also questioning this sanitized depiction of race in America; rather than confront these allegations, Traister concludes, white Americans preferred to keep alive the “soothing” fictions Cosby offered, and with it the idealized image of himself that he so carefully crafted over decades.

Historian Jelani Cobb made a similar case in the New Yorker, noting that Cosby is “a common heir to the body of stereotypes about [Black] sexual predation and the tormented history that accompany it.” The “lurid history of black men brought low by accusations, specious or not, of sexual contact with white women,” has led many Black Americans to suspect scandals of this sort are merely pretexts for “digital lynching.” Cosby, Cobb proposed, benefitted from Black reluctance to question the character of a man who had become an “embodiment of black dignity, a walking refutation of the worst ideas about us.” When Hannibal Buress unequivocally called Cosby a rapist, Cobb argued, Buress’s Blackness effectively gave white and Black Americans permission to entertain doubts about Cosby, even to see him as “a serial rapist who had masterfully manipulated both the white desire for an icon of post-racialism and the black desire for the type of dignified success that Cosby represented … This is not the conversation we would be having if Bill Maher or Jimmy Kimmel had called Cosby a rapist.”

Arguments like Cobb’s and Traister’s are compelling, because they have the ring of truth to them. Cosby’s depiction of affluent Black life was certainly a source of pride for many Black Americans and a comforting fantasy of “transcending race” for many white ones. It is also true that Cosby’s iconic status, enormous wealth, decades of philanthropy to Black causes, and his fondness for preaching Black personal responsibility over systemic change made him, as Cobb put it, “nearly unimpeachable” in the eyes of Americans of all races.

However, these observations can be both true and still insufficient to explain why Americans pretended for years that the allegations against Cosby didn’t exist. We have only to ask ourselves if we would have more readily believed the women who came forward if Cosby’s brand of Blackness were more disruptive, more subversive, or less respectable. Consider whether these women would have been more “credible” if Cosby were not an internationally renowned multimillionaire known for his largesse. The answer, clearly, is no.

These analyses arrive at the wrong conclusions because they start from the wrong premise. It is not who Cosby is that accounts for our long silence. It is who we are: a culture that does not believe people who share stories of surviving sexual violence. Were Cosby an unremarkable man of modest means, we would still doubt allegations like these, because that is what we do. The rationales we offer for why we doubt survivors are varied: the accused is a legend, or religious, or has been nice to us. The survivors have any number of real or perceived flaws. What doesn’t change is that when someone alleges rape, we immediately begin to grasp for reasons why that person is unbelievable.

The women who have come forward tell us that Bill Cosby got away with serial rape for decades. They tell us that they were rendered invisible for years, if not outright maligned, for the offense of reminding us of stories we would rather forget. In this, Cosby’s alleged behavior and the widespread denialism with which it was initially met is far from exceptional. To the contrary, this all is distressingly mundane. Getting away with rape—yes, even serial rape—is the norm. The results of a 2002 study by clinical psychologist David Lisak and Paul Miller, for example, suggest that serial perpetrators are responsible for as much as 90 percent of rapes on American college campuses.

The failure to consider Bill Cosby in the context of insights about gender, power, and violence that have come out of recent reporting on rape culture is perhaps an indication that more work needs to be done to connect the dots between different media narratives about rape. It has become common to discuss campus rape as a particular phenomenon, clergy abuse as another, gendered abuse in the workplace as still another, and so on. But we must be careful that in doing so, we don’t form artificial silos around different facets of rape culture. Not to the degree that we offer dramatically different explanations for the same phenomena—rapists getting away with rape, survivors not getting the support they deserve—depending on whether the perpetrator is a Bill Cosby, a Ben Roethlisberger, or the seemingly average Joe down the street. Their crimes, and others’ response to them, all take place as part of the same paradigm.

What we need are analyses that illuminate the commonalities between Cosby’s alleged behavior and the behavioral patterns of serial predators in other contexts: promises of professional advancement, lavish gifts, systematic boundary-testing, and grooming. The accounts of the survivors paint a picture of a man who targeted vulnerable women, often young adults just starting out in their careers, who were at a disadvantage in comparison to the much older, established Cosby. They describe a man who exploited the trust his public persona afforded him, isolated his targets, and then violated them.

In short, if Cosby got away with serial rape for so long, it’s because he did what habitual abusers do, and we did what we are accustomed to doing when survivors come forward with inconvenient truths. We chose to pretend they didn’t exist.

Any accounting of why Cosby got a pass must start from the foundational point that as a society, we often do not believe survivors, or consider ourselves to be the true victims in the situation. We must situate celebrities accused of sexual violence—and public perception of these celebrities and alleged victims—as part of the broader terrain of rape culture, in order to work toward preventing similar injustices in the future.