Poorly Defined Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Used to Blame, Criminalize Mothers

The Alaska legislature recently approved a project that will place free pregnancy tests in bar bathrooms as part of a larger campaign to raise awareness about fetal alcohol syndrome. But what is fetal alcohol syndrome, and could this effort possibly help address it?

Beginning in December, female customers in bars across Alaska will have access to an unexpected resource: pregnancy tests. The Alaska legislature recently approved a project that will place free tests in the bathrooms of 20 bars in the state. The study is part of a larger campaign to raise awareness about fetal alcohol syndrome, a spectrum of physical, mental, and behavioral disabilities long assumed to be caused by drinking to excess during pregnancy.

Alaska state Sen. Pete Kelly (R-Fairbanks), who earlier this year declared that “birth control is for people who don’t want to act responsibly,” is the driving force behind this new crusade. Alaska has one of the highest rates of fetal alcohol syndrome in the country. A 2010 report estimated that as many as 126 infants born each year in the state show signs of prenatal exposure to alcohol. But Kelly’s argument isn’t just a classic “think of the children” line. He claims fetal alcohol syndrome is responsible for a range of social ills, including suicide and domestic violence.

The logic behind the pregnancy test intervention is simple. Half of pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, so it’s possible that some patrons do not know they are pregnant when they order a beer or a shot of vodka. The pregnancy test is a nudge in the right direction—a reminder to make sure they’re not endangering a developing embryo.

Many states mandate posters in the bathrooms of bars or restaurants that warn about the dangers of prenatal alcohol consumption—“a pregnant woman never drinks alone”—but these signs have done little to curb the incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome, according to Robert Sokol, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Michigan’s Wayne State University. The researchers at the University of Alaska who are implementing the new study want to find out if a pregnancy test dispenser does a better job of getting women’s attention. The dispensers, originally piloted in Minnesota, have yet to be studied, so their effectiveness is still unknown.

Sokol says this approach is clever because instead of putting billboards on highways or doing a PSA blitz, the intervention is concentrated in bars, places where women could, according to Sokol, be engaging in risky behavior before they even know they are pregnant. “There hasn’t been much research on this issue that has focused in bars,” he says. “If a woman is pregnant and in a bar, then that’s someone we know is likely drinking, and it’s someone we should be talking to.”

Not everyone agrees. To others, this approach is a new riff on an old theme, one that has been frequently replayed since fetal alcohol syndrome was first given a name in 1973. In this refrain, concern about the mother’s well-being is submerged beneath fears about the harm she might inflict on her fetus. The initiative assumes that any pregnant woman in a bar is drinking alcohol, putting her in a place of public surveillance. “This kind of approach isn’t about empowering women to make healthy decisions—it’s about creating implicit responsibility for the outcomes of their pregnancies,” Farah Diaz-Tello, a staff attorney with National Advocates for Pregnant Women, told Rewire. “It says that we’re concerned about women’s health only so that they can keep their bodies hospitable to pregnancy. If they don’t, they’re irresponsible—they’re bad mothers.”

The pregnancy test initiative is the brainchild of Jody Allen Crowe, the executive director of a Minnesota nonprofit called Healthy Brains for Children. Crowe, a former school superintendent with a master’s degree in public school administration, founded the group in 2008, shortly after self-publishing a book that claims to reveal “the undeniable connection between school shooters and their mother’s [sic] alcoholic behaviors.” Crowe, who is coordinating delivery of the pregnancy dispensers to Alaska and has served as a resource for legislators throughout the process, envisions a world in which taking a pregnancy test before drinking is as normal as designating a sober driver for a party: “We need to get the message out there that every drink a pregnant woman holds in her hand has the potential to take potential away from her child.”

The History of Drinking During Pregnancy

There was a time in the not-so-distant past when a statement like Crowe’s would have seemed outlandish—even misinformed. Alcohol was, throughout the mid-20th century, as much a part of a woman’s pregnancy as prenatal vitamins are today. A glass of port helped with sleep; some sherry before a meal could rouse an unwilling appetite. A cocktail and a cigarette could help an anxious mother-to-be relax. The only reason not to indulge to excess was the empty calories.

Some obstetricians even believed that alcohol could halt preterm labor. When women showed up at the hospital before their due date, complaining about steadily advancing contractions, doctors would send their patients home with instructions to drink a glass of wine. Others received pure alcohol intravenously in the hospital. In her book Conceiving Risk, Bearing Responsibility: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and the Diagnosis of Moral Disorder, Princeton sociology and public policy professor Elizabeth Mitchell Armstrong writes that in doctors’ recollections, women subjected to this regimen “got so [they] smelled like a fruitcake.”

Attitudes toward alcohol consumption slowly began to change after 1973, when a group of doctors published a series of case studies in the medical journal The Lancet on children with development disorders, small eyes, unusually thin upper lips, and other abnormalities. The authors traced the cause for what they called a “tragic disorder” to maternal alcoholism. The women in the study had been dependent on alcohol for more than nine years; more than half experienced serious withdrawal symptoms. They were not the same women who were having a glass of port to help them sleep, but rather women who already struggled with serious alcohol dependency.

Over the following decade, public characterizations of fetal alcohol syndrome shifted, thanks to the flurry of research that followed the publication of the 1973 Lancet article. Thousands of studies on fetal alcohol syndrome were published between the mid-1970s and the late-1980s, many of which argued that the condition wasn’t just confined to women with severe alcohol problems. There was no clear consensus on how much alcohol was safe to drink, so women were told to abstain entirely.

The studies were, in general, small and inconsistent. The size of a drink was rarely defined—raising questions about whether women who reported their drinking habits were talking about a double shot of vodka or a glass of wine—and many included a handful of alcohol-abusing mothers, which may have skewed the sample. Other studies were performed on rats, who were given doses of alcohol that would have amounted to binge drinking in a human. It was clear that heavy drinking during pregnancy did carry a strong risk for fetal complications, but the evidence about light and moderate drinking during pregnancy remained unreliable. Nevertheless, alcohol consumption during pregnancy was increasingly represented, both in research papers and in the media, as an individual moral choice born of a mother’s selfish and reckless actions. Women needed to learn, in the words of a professor of dentistry writing in 1989, that “life is not a beer commercial.”

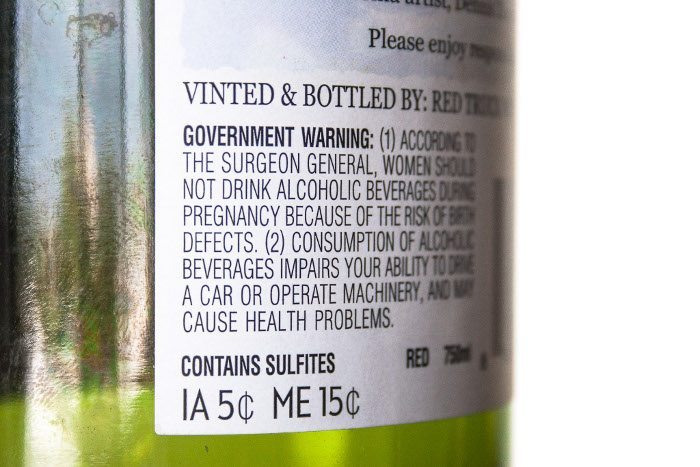

Faced with what was increasingly framed as a national crisis, policymakers sprang into action. In 1981, the surgeon general of the United States issued a warning to pregnant women, advising them “not to drink alcoholic beverages and to be aware of the alcoholic content of food and drugs.” Throughout the 1980s, states and localities launched public awareness campaigns about the hazards of alcohol consumption for expectant women. In 1988, the United States became the first and only country to mandate a warning label on alcoholic beverages outlining the dangers of drinking during pregnancy.

The Science Behind Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Some women got the message. The numbers of women who drank any amount of alcohol during pregnancy declined from 32 percent in 1985 to 20 percent in 1988. Today, the number hovers around 12 percent. The number of women who binge drink during pregnancy, however, continues to hover between 2 and 3 percent. What, exactly, fetal alcohol syndrome is also remains a subject of great concern. In the United States today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that anywhere between 1,000 and 40,000 babies are born with symptoms of the disorder each year. This wide range is only conjecture, in part because some states don’t require tracking of fetal alcohol syndrome diagnoses, making data collection difficult. But the numbers are also vague because the diagnostic criteria for the condition are subjective—there is no clinical test for fetal alcohol syndrome. Doctors screening for fetal alcohol syndrome are told to look for distinctive facial characteristics: thin upper lips and flat features. These obvious physical signs, however, only appear in children who were exposed to heavy drinking in utero.

The other assumed symptoms are more nebulous; they include growth problems (which often resolve themselves in early childhood), poor coordination and muscle control, cognitive defects, and developmental delays. These problems are hard to definitively attribute to prenatal alcohol exposure, because they could also be the result of poverty and a dysfunctional home life. Behavioral issues are also among the symptoms of fetal alcohol syndrome outlined by the CDC, although there is little concrete evidence to suggest that these problems are biologically linked to drinking while pregnant.

In one frequently cited study, researchers surveyed a group of 400 patients who were diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome at birth. These patients had a wide range of behavioral problems—ranging from inappropriate sexual behavior to incarceration to “disruptive school experiences”—but the authors admitted that they did not account for “environmental” factors like child abuse and neglect, living with an alcoholic parent, or being put into foster care. Yet environmental stressors likely had a profound influence on the study’s sample. Eighty percent of the respondents were not raised by their biological mothers.

Part of the problem is the lack of a clear distinction between the syndrome itself—a discrete collection of symptoms that include severe developmental disabilities and is associated with chronic alcoholic mothers—and other outcomes that may be associated with drinking but are also more difficult to diagnose and identify. Conflating the two suggests that they have the same cause, and also suggests that moderate drinking is the cause of the most devastating cases of fetal alcohol syndrome.

Because fetal alcohol syndrome is difficult to treat (and the small treatment programs that exist are underfunded), public health programming has focused mostly on convincing pregnant women not to drink. But part of the tension inherent in any prevention plan—like Alaska’s pregnancy test initiative—is the debate over who’s at risk. One of the most immediate challenges is that obstetricians themselves are not in agreement about how much alcohol can be safely consumed during pregnancy. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists warns that “no amount” of alcohol is safe during pregnancy, but in a 2010 survey of OB-GYNs, only 60 percent agreed.

There’s a general consensus that binge drinking during pregnancy—consuming five or more drinks in one sitting—is risky. But the research still hasn’t proved that small amounts of alcohol cause ill effects. When University of Chicago economist Emily Oster was researching her book Expecting Better, she combed through hundreds of studies and found “basically no credible evidence that low levels of drinking (a glass of wine or so a day) have any impact on your baby’s cognitive development.” The few studies that showed negative birth outcomes as a result of light drinking were “deeply flawed.” Just as the research on patients affected by fetal alcohol syndrome failed to take environmental factors into account, these studies paid no heed to the complementary effects of other drugs. In one, many of the study’s “light drinkers” were also using cocaine.

The studies that have attempted to incorporate the effects of alcohol alongside environmental factors like poverty, instability, and use of other drugs have concluded that the women who are at risk for exposing their fetus to alcohol in utero are often low-income, with poor nutrition and little access to prenatal care. Some studies also show that cigarettes can exacerbate the negative effects of fetal exposure to alcohol.

These factors work in tandem—especially among marginalized groups like American Indian and Alaska Natives, who have some of the highest rates of fetal alcohol syndrome in the country. Poverty, social isolation, a history of trauma, and poor health care all encourage substance abuse. Alaska Native communities are overwhelmingly rural, making health care difficult to access. Nearly 30 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native Americans live in poverty, and more than 15 percent lack health insurance. A series of reports published by the CDC earlier this year showed that between 1999 and 2009, the mortality rate was 46 percent higher among American Indian and Alaska Natives, compared to the general population, due largely to higher death rates from cancer and infectious diseases.

Living in remote, isolated towns also spurs depression and alcoholism. Alaska Natives are four times as likely as non-Native Alaskans to commit suicide; they are also twice as likely to need treatment for alcohol addiction. Mental health problems and alcohol abuse can also encourage a culture of violence against women. Alaska Native women are ten times as likely as non-Native women to be sexually assaulted.

In this context, the high incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome in Alaska—where Alaska Native women are five times as likely as non-Native women to give birth to a child with the condition—is less a result of women’s individual choices than a total breakdown of the social safety net. But instead of investing in the chronically underfunded Indian Health Service, the primary source of health care for most Alaska Natives, or devoting more funds to treatment programs that incorporate the loss of cultural integrity, which is also considered to be a major driver of alcoholism among American Indians, public awareness campaigns that target the entire Alaskan population are still the prevention tool of choice.

The emphasis on fetal alcohol syndrome as a problem that could afflict any child whose mother drank any amount of alcohol during pregnancy—rather than a symptom of severe substance abuse by relatively few women—makes it easier, says Janet Golden, a medical historian at Rutgers University, to justify solutions like signs or pregnancy tests in bathrooms—a cheap fix, compared to inpatient treatment for chronic alcoholics. These broadcast public health campaigns allow politicians to transfer responsibility for fetal alcohol syndrome onto the mothers themselves, rather than using state resources to help treat alcoholism and the other health problems caused by poverty and marginalization. “Women who drink during pregnancy are understood as willfully harming their fetuses,” Golden says. “There’s no acknowledgment that alcoholism is a severe health problem that’s killing women too. I don’t see any concern for those women’s ability to access care.”

Helping or Harming Women?

In the years after fetal alcohol syndrome was first diagnosed, attempts to discourage individual women from drinking during pregnancy have become increasingly punitive. In 1990, two years after the surgeon general’s warning began to appear on alcohol packaging, a pregnant woman in Wyoming seeking protection from her abusive husband was charged with felony child abuse after the police discovered she was drunk. Fears about “crack babies”—children born to low-income, minority mothers who were using cocaine—were also spiraling, and prosecutors were creative in using a wide range of statutes to charge women for actions that potentially harmed their fetus. Women found themselves facing accusations of abuse and neglect of children, “delivering” drugs to minors through the umbilical cord, and assault with a deadly weapon (cocaine). Most of these charges were struck down or reversed by judges who pointed out the logistical and constitutional questions they raised. How were women to know what counted as endangering their fetus? Could drinking coffee during pregnancy or missing a prenatal visit become a criminal act?

In response, policymakers turned to the civil code to reinforce penalties for drug and alcohol use during pregnancy. Eighteen states redefined civil child abuse to include prenatal substance use. Four states—Oklahoma, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and South Dakota—went further, passing laws that authorized involuntary civil detention of women who drank or used drugs while pregnant. The Wisconsin and South Dakota statutes allowed detention not just in the case of harm to the fetus—an ill-defined term under the best of circumstances—but when a woman’s alcohol use appeared to “lack self-control.” Alaska legislators have considered an involuntary commitment law for pregnant women who consume alcohol several times. Rep. Pete Kelly, the force behind the pregnancy test initiative, said earlier this year that such a measure isn’t out of the question in the future.

The brunt of these laws, which are vaguely written and selectively applied, falls on low-income women and women of color. A study published in 2010 by Lynn Paltrow, the executive director of National Advocates for Pregnant Women, and Jeanne Flavin, a sociology professor at Fordham University, found that Black and Native American women were disproportionately represented among the pregnant women arrested or subjected to a forced medical intervention because of substance use. Only about 10 percent of the claims against the 413 women in the National Advocates for Pregnant Women study were related to alcohol—most of the time, the substance in question was cocaine—but they established a strong precedent for health providers, social workers, and even neighbors to report women who were drinking during pregnancy.

This is especially true in Alaska. Rosalie Nadeau, the CEO of Akeela, the state’s largest residential treatment provider for pregnant women, says that most of the women in her programs were reported to child protective services, which usually triggers a custody dispute. “The ones who have children have usually either lost their kids already or are in danger of losing them,” Nadeau says.

The pattern of reporting women for substance use would be less troubling if there were more programs like Akeela, which offers a range of residential and outpatient services for women with children. Part of Akeela’s goal is to help women achieve sobriety so that they can regain lost custody rights. But policymakers have failed to pursue treatment with the same zeal that they have approached punishment. Only 18 states have created or funded programs specifically targeted at pregnant women with substance abuse problems, and the waiting list is always long. Nadeau’s program, despite being the biggest in Alaska, can only accommodate 15 women at a time. Any more, and Akeela risks losing the Medicaid dollars that keep its treatment centers open.

The dearth of funding for treatment programs like Akeela is alarming, considering that women with entrenched alcohol abuse problems are at highest risk for giving birth to a child affected by fetal alcohol syndrome. These women, chemically dependent on alcohol, are unlikely to stop drinking because of a pregnancy test in a bathroom.

But helping a targeted minority of women is not the goal of the new Alaska study. “This intervention is not specifically intended for women who have chronic alcohol problems,” David Driscoll, an associate professor of health and social welfare at the University of Alaska and the lead researcher on the project, told Rewire. “It’s intended for those women who are not aware yet that they’re pregnant and are not aware of the risks of [fetal alcohol spectrum disorder].”

Margo Singer, vice president of the National Association for State Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder Coordinators, says that fetal alcohol syndrome prevention requires a variety of approaches. There are universal campaigns—like the pregnancy test dispensers—that attempt to raise awareness. Then there are more carefully tailored strategies, which educate family planning professionals, doctors, and social workers about how to talk to women about the dangers of alcohol abuse. Finally, there are counseling programs for women in alcohol treatment programs, which emphasize contraception alongside warnings about the harm associated with heavy drinking during pregnancy.

In a perfect world, Singer says, there would be funding for all of these initiatives. But since 2012, federal dollars for fetal alcohol syndrome prevention were slashed. The $400,000 allocated for the pregnancy test intervention is, in this climate, a tidy sum. The University of Alaska researchers’ plan to determine whether the dispensers work will be a new addition to the literature on fetal alcohol syndrome prevention. But they may find that the intervention, like the bathroom signs, simply doesn’t work. “If it helps one woman, that’s a good thing,” says Singer. “But we do have to ask the questions: Is this effective? Has it been tested? Is this really the initiative we want to promote?”

In a state with a budget deficit, David Driscoll notes that it’s “laudable” that Alaska legislators allocated money for fetal alcohol syndrome prevention. The pregnancy dispenser project will be accompanied by a statewide public awareness campaign and a program targeted at Alaska Natives in remote parts of the state. But Rosalie Nadeau questions why the state is investing in a program that has yet to be tested, when treatment for alcohol abuse is chronically underfunded.

There’s near-uniform agreement that access to free pregnancy tests will be good for women, regardless of the context. But the Alaska initiative doesn’t include money to provide contraception, which Singer says is a crucial part of any effort to reduce fetal alcohol syndrome. A study conducted by researchers in Washington state revealed that 81 percent of women at risk for fetal alcohol syndrome had no birth control, although 92 percent wanted some form of contraception. Driscoll says that condoms will be available alongside the pregnancy test dispensers, although he did not specify how they would be funded. The contraception will be added separately, because when Jody Allen Crowe first piloted the program, birth control was not part of his design. “It’s just not our goal,” he says. “We want to stop alcohol during pregnancy. We don’t want to stop the pregnancies themselves.”

This, according to Golden, does a fundamental disservice to women who might take steps to prevent pregnancy if they had the education or the resources. “Historically, there’s been an expectation that women are so primed to be mothers that if they see a pregnancy test or take it, they’ll stop drinking immediately,” she says. “The women who are chronic alcoholics can’t, so we label them bad mothers. A lot of these women would stop drinking during pregnancy if they could. We just don’t give them the resources and care they need to do it. It’s something we see again and again. We keep going for the inexpensive fix that doesn’t actually solve the problem.”