Choice, Surrogacy, and a Troubling Response to My Previous Commentary on Criminalization

Last week, Rewire published a piece in response to an earlier commentary I wrote about what was being billed as a feminist effort to criminalize surrogacy in Kansas. Much as I respect them, it appears the co-authors of that article responded to a straw man.

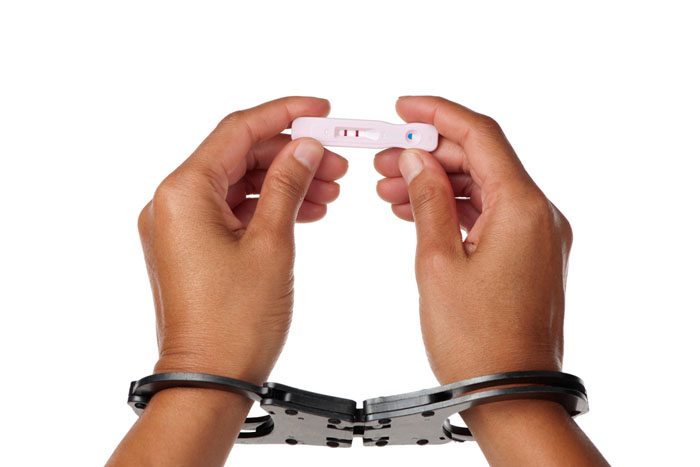

Last week, Rewire published a response to an earlier commentary I wrote about what was being billed as a feminist effort to criminalize surrogacy in Kansas. If enacted, SB 302 would make surrogate parents, gestational carriers, and anyone who “is involved in, or induces, arranges or otherwise assists in the formation of a surrogate parenting contract” liable to up to a $10,000 fine or imprisonment of up to one year.

My commentary specifically critiqued what were presented as feminist arguments in favor of throwing people in jail on the basis of carrying a surrogate pregnancy to term. The rebuttal took no position on this matter while at the same time claiming my argument and concerns were “simplistic.” The authors disagreed loudly with me on a “litmus test for feminists” that I never proposed without ever taking a position on the central concern in my article: laws promoting jail time for surrogate families. As my colleague Emily Crockett noted independently on Twitter, I “was not arguing against ‘responsible policies and oversight’ re: surrogacy, rather CRIMINALIZATION.” Much as I respect them, it appears the co-authors of “Invoking ‘Choice’ When Discussing Surrogacy as a Feminist Concern is a Mistake,” responded to a straw man.

That said, in the interest of moving the discussion forward, I would like to engage with some of the points raised by the authors in their response, and raise some additional points for consideration. After all, I agree that, yes, surrogacy is a complex issue, and further, I believe readers are up to the task of considering the issues and making up their own minds.

The authors raise a number of legitimate issues, including the fact that surrogacy can take place in a market context, and that means “we should look closely at workers’ safety and rights.” Further, they address the fact that surrogates may have fewer economic resources than those families for whom they have chosen to bear children. These issues are important. Many of those who wish to outlaw surrogacy or place strict regulations on it have a strong, visceral reaction to the fact that money may change hands or contracts may be drawn up in the creation of family.

However, we may wish to consider three things: One, the inference of exploitation does not account for women who say they enjoy carrying pregnancies to term for other families. Two, pregnancy and especially childbirth are all-encompassing deals; taking those burdens on for another may well be worthy of compensation beyond a so-called labor of love. Three, fair contracts offer the possibility of protections, including clauses that could enshrine a core tenet of reproductive rights: that a pregnant woman direct the course of her own health care and outcomes—including but not limited to retaining the power to pursue abortion in consultation with her medical team, and retaining the power to decline a c-section.

There are a number of points the authors raise about the operation of surrogacy in an international context, and in this area it’s prudent to exercise caution in drawing broad parallels when crafting domestic policy here in the United States. The issue of black markets abroad is sobering, but wouldn’t it be the case that enacting strict regulations in the states could encourage rather than discourage the emergence of bad actors? After all, as many families facing infertility can attest, the drive to have children often doesn’t go away when the means to do so seem to disappear. To consider another case of homegrown solutions crafted to address international issues, we have seen how the situation of son preference in other countries has been repeatedly invoked in the introduction of racist, sexist abortion bans in the United States that do not address the issue of son preference in other countries but rather promote racial profiling and make abortion less accessible for women of color here at home.

It is also important to use caution when drawing broad conclusions about banning surrogacy based on the situation of women in other countries. For example, France is listed in the piece as one country that has banned surrogacy but is “more ‘feminist’ and protect[s] abortion rights far more strongly than the United States.” Some would argue that France has a more macho culture than the United States—during the height of the coverage of sexual assault charges against Dominique Strauss-Kahn, French feminist groups rose up decrying not just the alleged crimes but also the “inequalities and machismo of French society.” Further, France may offer reimbursements for abortion procedures, but abortion is only legal up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. Is that “protect[ing] abortion rights far more strongly than the United States”? That’s very debatable and also ignores a broader context about the access and availability of health care more generally. In any case, conflating the institution of surrogacy bans with the greater realization of feminism and abortion rights is neither germane nor descriptive of a cause-and-effect relationship; even if it were, it’s very debatable if more rights in one area justifies circumscribing a separate set of rights in another. Firmly, I argue not.

There are a number of additional points that I would like to introduce that merit careful consideration, especially when we consider what was framed as feminist arguments for the legislation I originally referenced, SB 302 in Kansas.

While my original piece focused on the testimony provided by two women in favor of SB 302, one additional person testified in favor of the bill. Mike Schuttoffel serves as executive director of the Kansas Catholic Conference and said in his testimony that surrogacy “violates the sacred bond of mother and child,” offering adoption as an alternative solution. This is important to discuss.

Some families headed by heterosexual couples thoughtfully choose surrogacy after facing problems with fertility. Surrogacy may play a special role in the formation of same-sex families, especially households headed exclusively by men. Is adoption a better answer? Perhaps for some families, but arguing that adoption is the sole correct answer for LGBT families or families dealing with infertility rings about as helpful as arguing that adoption is the perfect answer to eliminating the need for abortion. In modern times as in others, the experience of family varies dramatically from person to person, and prescribing what is best for families facing infertility doesn’t solve problems. (Janna Zinzi has a thoughtful piece on infertility, shame, and how Melissa Harris-Perry is sparking a national conversation about fertility and family through open discussion of how she welcomed a daughter through surrogacy here.)

Going back to a policy perspective, the Kansas bill can be seen as yet another part of a national effort to make pregnant women criminals. In Tennessee, for example, SB 1391 criminalizes drug use during pregnancy and offers an instructive lens for examining the Kansas situation. That’s because while women-focused proponents of the surrogacy criminalization bill argue that women in poverty need to be protected from economic pressures to bear children for another family, the reality is that the bill criminalizes everyone and facially neutral criminal laws are not applied proportionally on the basis of race and class. (My colleague Imani Gandy has an excellent commentary on how Tennessee’s pregnancy criminalization law will hit Black women the hardest, however race-neutral the bill appears to be, here.)

Regarding tactics and alliances, let’s also think carefully about whether and when it’s a good idea to partner with members of the “pro-life” advocacy community in regulating reproduction and surrogacy. The response article to my original piece appears to stand in solidarity with the arguments I deconstructed that Jennifer Lahl and Kathleen Sloan presented at the hearing in favor of SB 302. Perhaps this is no mistake—it could be that the co-authors agree with the presentation of that testimony in favor of criminalizing surrogacy, or it could be something else. We don’t know. What we do know is that Judy Norsigian, who co-authored the piece has, like Sloan, worked with Jennifer Lahl to promote Lahl’s anti-surrogacy film, Eggsploitation. This is important because this film was used as a prop in the campaign to criminalize surrogacy in Kansas; indeed, Lahl and Sloan headlined a screening of the film in Topeka the same day they testified for SB 302.

My point is not to single people out but to point out these relationships and interconnections. While I never argued for a “litmus test for feminists” and am not doing so now, it is fair to on a broader level question if these partnerships are a good idea. Informal or formal partnerships with anti-choicers might make sense in family policy areas where we should be able to find common ground (establishing fairness for pregnant workers, the right to nurse in public, and guaranteed paid family leave, to name a few), but do they make sense in the realm of reproductive health and medicine? Even if areas of agreement were to arise, the anti-choice movement’s disdain for fact-based arguments as well as its failure to address violence within its ranks creates serious reason for pause.

I urge the authors of the response piece as well as our readers to engage vigorously with the substance of my original piece and with these issues. Is a $10,000 fine and 365 days in jail an appropriate way to deal with concerns about surrogacy? Are criminalization, outright bans, and stringent regulations created with the intention of making new surrogate parenting arrangements difficult to outright impossible “thoughtful” approaches to these concerns? Is it ever OK to throw some women in jail for the sake of an invoked greater good? Under which circumstances is it acceptable to create new restrictions on reproductive rights?