Anti-Choice Lawyer Harold Cassidy Owed Millions in Taxes and Debts, Records Indicate

It's "ironic," explained state Rep. Peggy Gibson. Harold Cassidy, a lawyer and self-style anti-choice crusader, is “invasive of women’s private affairs, and then he says his affairs are private, when women have no right to privacy."

With research by Imani Gandy.

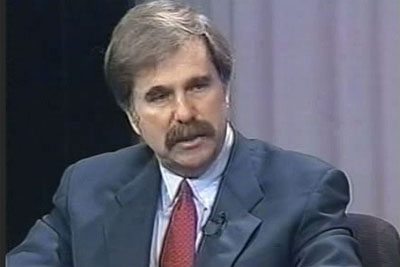

Harold Cassidy isn’t afraid to cast judgment when it comes to women’s rights.

The lawyer and self-styled anti-choice crusader calls surrogacy a “terrible practice” that “shouldn’t even be considered by rational people,” and says abortion is an “experiment,” that “society” doesn’t understand—least of all, women.

“What the women of this country have been told is that they’re exercising a right,” Cassidy said in an unattributed television interview that is posted to his New Jersey law firm’s website. “They’re not exercising a right. They’re waiving the most important right they have.”

In Cassidy’s view, that “right” is connected to what he sees as an intrinsic bond between a woman and her children, especially her fetus. “Really there is no chance of having an informed, voluntary waiver of this fundamental right until the baby is born,” Cassidy said in that TV interview.

By his own account, Cassidy has played a decades-long role in shaping abortion laws throughout the United States.

“Beginning in the mid 1980’s, I have been consulted by legislators in many states,” he wrote in an eight-page statement to Rewire.

Nowhere has that influence been more pronounced than in South Dakota, where Cassidy has advised legislators on some of the country’s most restrictive abortion laws, and has represented anti-choice crisis pregnancy centers in litigation.

New information obtained by Rewire raises questions about Cassidy’s credentials to assert his moral authority over the women he says he wants to “protect.”

A review of public documents discloses that Cassidy and his wife, Randee, racked up millions of dollars in unpaid taxes and debts beginning in the late 1980s.

Despite multiple requests over nearly two months, Cassidy declined to explain how he and Randee amassed these debts, or to provide more detail on the individual filings or proceedings.

In our review of the documents, Rewire attempted to remove any duplications. The figures contained in this report are based purely on publicly available information.

According to documents, in June 2006, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) sought nearly $1.6 million in unpaid taxes, penalties, and interest from the couple after they failed to fully pay federal taxes beginning in 1986 until the early 2000s, with the exception of 1987.

It’s not just the federal government that resorted to legal proceedings to recoup unpaid debts from Cassidy, public documents show.

The State of New Jersey lodged up to eight filings against Cassidy between March 1989 and August 2013, for what appears to be a total of $200,212 in unpaid taxes, interest, and penalties. (Each of these filings was made on a different date, and has a different case ID code.)

Private individuals and organizations have also had to rely on the courts to force Cassidy to pay his debts, the documents show.

For instance, in 2010, an entity listed as “Pope John XXIII Regional Cath” won a civil judgment against Cassidy for $4,632. There is a Catholic high school called Pope John XXIII Regional High School located in Sparta Township, a 90-minute drive from Ocean Township, New Jersey, where the Cassidys live, according to the most recent public documents. A school official told Rewire that he was unable to confirm whether the school had sued Cassidy, and Cassidy did not answer our specific question on this point.

In response to multiple requests for more details on these judgments and liens, Cassidy provided the following comments, as part of the eight-page response:

The amount you claim I owe is incorrect and there is no way for you to know how much I paid, or how many hundreds of thousands of dollars I paid on those taxes with the sale of assets. Nor, is there any reliable way for you to know that, in fact, virtually all of my other debt is paid off.

In a later email, Cassidy added, “The three judgments you identified had been paid off long ago (whether or not you can find them discharged of record),” but he did not clarify which judgments he was referring to.

Upon learning of Cassidy’s financial track record, South Dakota Rep. Peggy Gibson (D-Huron) called the attorney a “hypocrite.”

“He’s so financially irresponsible and yet he’s supposed to be this big ‘savior’ of women,” Gibson said. “He can’t manage his own affairs. Why would he be able to manage the affairs of South Dakota women, and their most private affairs—their health care and their reproductive decisions?”

State Sen. Angie Buhl O’Donnell (D-Sioux Falls) said it was “unfortunate” that Cassidy had such influence in the state.

“We, as a state, have bought everything that this guy has told us on how to shape policy, about how women should live their lives, when he could clearly use some advice on that front himself,” she said.

Telling Women They Can Never “Choose” Abortion

Though relatively unknown on the national political scene, Cassidy has had an outsized impact on framing the national debate over abortion.

For decades, the New Jersey lawyer has been honing legal arguments that focus less on a woman’s fetus, and more on women themselves, arguing that women suffer grievous psychological effects after undergoing an abortion.

Cassidy has consistently argued that a woman’s relationship with her children—including a fetus in the earliest stages of development—is “one of the greatest interests a woman possesses in all of life,” regardless of whether the particular woman in question agrees with him.

And because, as Cassidy sees it, that “interest” is so important, preserving it amounts to a constitutional right that the state can protect.

That’s legalese for saying that, in Cassidy’s view, states can encroach upon, or even ban, abortion, because of their interest in protecting the relationship between the woman and the fetus.

Cassidy’s ideas have caught on. The anti-choice group Americans United for Life said earlier this year that it is now focusing on model bills that purport to protect women from the dangers of abortion. Many of the regulations that require clinics to have wider hallways, insist that abortion providers maintain admitting privileges at certain hospitals, and force doctors to perform medically unnecessary vaginal ultrasounds on women seeking abortions, are couched in “woman-protective” terms. The intent, however, remains the same: to end all forms of abortion care in the United States.

Many of the nation’s most extreme anti-choice laws have been proposed, and in some cases passed, in South Dakota, where Cassidy was last listed as a lobbyist in 2005, according to the secretary of state’s website.

A 2011 profile in Mother Jones detailed how Cassidy influenced the state legislature’s effort to enact an outright abortion ban in 2004:

The new text was focused more on the mother—and Cassidy’s fingerprints were evident throughout: “The state has a duty to protect the pregnant mother’s fundamental interest in her relationship with her unborn child,” it stated, adding that abortion creates a “significant risk” of severe depression, suicide, and post-traumatic stress disorders. It was the most prominent platform the “abortion hurts women” argument, and Cassidy, had ever had.

The bill, the first of a series of unsuccessful attempts by South Dakota legislators to ban abortion, was vetoed by the governor. (Two subsequent attempts were shot down at the ballot box.) But pro-life legislators were impressed by the gut-wrenching testimony Cassidy had arranged. In 2005, they created a task force to study abortion’s harmful effects. Cassidy was again called in to help, and the task force published a lengthy report citing the stories of his witnesses and recommending that abortion be banned. It was a huge moment for Cassidy and his allies: For the first time, sketchy findings about abortion’s emotional harm to women had a state’s official imprimatur.

In 2012, Cassidy had a significant win when the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit upheld provisions of a different law that requires doctors to tell women seeking abortions that there are “known medical risks of the procedure and statistically significant risk factors,” specifically, “increased risk of suicide ideation and suicide,” even though the medical consensus is that such claims are false, as Judge Diana E. Murphy noted in her dissent.

Today, Cassidy is representing two South Dakota crisis pregnancy centers—known as “pregnancy help centers” in that state—in litigation over provisions of a 2011 law that requires women to go for “counseling” at the explicitly anti-choice centers, as a condition of accessing an abortion.

The case, Planned Parenthood of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota v. Daugaard, remains in early stages. Because that litigation is ongoing, neither Cassidy nor the plaintiffs—Planned Parenthood of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota—could comment on the case.

Cassidy downplayed the influence of his personal beliefs on the work he does in South Dakota.

“In the case of South Dakota, the pro-life policies originate in the state with its people and the legislators elected to represent them,” Cassidy wrote in his statement to Rewire. “Any lawyer who is consulted, such as myself, only lends his expertise to help the people of the state and their elected representatives to successfully achieve their objectives.”

“South Dakota is a pro-life state. The legislature is pro-life, reflecting the values of the voting public.”

In reality, South Dakotans have twice rejected bills that would have banned abortion in their state.

In November 2006, voters rejected a ban that had been supported by the legislature, using a legal mechanism that South Dakota shares with many states, which enables citizens to initiate or vote down laws by collecting enough signatures to have the laws placed on a ballot.

Again in 2008, South Dakotans voted against another sweeping ban that would have placed criminal penalties on doctors who performed abortions except in the case of rape, incest, or to protect a woman’s health.

Cassidy Says Business Affairs Are Private

If Cassidy was coy in giving Rewire information about his activities in South Dakota, he was even less forthcoming about his own financial track record.

We obtained court documents related to bankruptcy proceedings begun in July 2005. A bankruptcy “disclosure statement” signed by Harold and Randee Cassidy that month put the couple’s total debt at more than $2.18 million, with assets of $779,710. The debt included just under $121,213 owed to New Jersey.

In a 2007 filing, Cassidy noted that the IRS had demanded nearly $1.59 million in unpaid taxes, penalties, and interest in June 2006.

But the documents show that Cassidy was optimistic about his prospects of paying off his debts. In an exhibit to the couple’s “plan of reorganization,” lodged on the same date as the disclosure statement, Cassidy said he expected a net pre-tax income of $272,400 from his law firm for the last six months of 2005, and an additional $588,500 in the following two years.

“To cover contingencies, I would list my projected income before taxes as $360,000.00 to $400,000.00,” he wrote.

Yet, records show that the Cassidys continued their pattern of failing to pay debts. In September 2010, a New Jersey legal support services company sought $11,640 from Cassidy and his firm. And in July 2012, an entity called State Shorthand Reporting obtained a judgment for $3,227 against Cassidy. The State of New Jersey lodged additional claims as well.

Deliberate failure to pay income tax can in some instances lead to professional discipline against attorneys. However Barbara Cristofaro, a spokesperson for the New Jersey Office of Attorney Ethics, told Rewire that her office has never disciplined Cassidy, and that he has remained current on his annual registration fees to practice law in that state.

Rewire spent weeks negotiating the terms of a possible on-the-record interview with Cassidy, in order to fully understand why he had racked up bankruptcies and dozens of judgments and liens and had failed to pay debts ranging from thousands of dollars down to a few hundred, to companies that appear to have transcribed court proceedings for him, as well as to a department store, and, it seems, to a New Jersey Catholic high school.

Cassidy ultimately declined to speak with Rewire on the record.

He did, however, allude to possible reason for his financial travails, in the written response he provided.

“Quite frankly, my financial affairs are none of the business of the abortion industry and Rewire,” he wrote. “Whether I am a poor businessman, or because decades of pro bono work has forced me to struggle financially, is completely irrelevant to the moral strength of my legal work, and certainly irrelevant to the moral authority of the clients I serve.”

Cassidy elaborated this idea:

Even in the case of highly regarded public servants whose public works are greatly admired, their personal indebtedness and the poor business judgment which usually accompanies it, never diminishes their moral authority on the big moral issues of their day.

For instance, Presidents Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant and William McKinley, all filed bankruptcies. While they may have been financially bankrupt, they were anything but morally bankrupt.

State Rep. Gibson said she found Cassidy’s statements “ironic.”

“He’s invasive of women’s private affairs, and then he says his affairs are private, when women have no right to privacy,” she said.

“It’s amazing that he would compare himself to these figures of American history who have done so many lasting, good things for our country.”

More Anti-Choice Bills Proposed in South Dakota

Another crop of anti-choice bills has already been introduced in South Dakota this year, including measures that would prohibit sex-selective abortions, prevent centers that provide either adoption or abortion from registering as “pregnancy help centers,” and provide medical care for “certain unborn children.”

Cassidy refused to say whether he’d had any involvement in those bills, but when Rewire asked Cassidy whether he was linked with two other bills—which would place civil and criminal penalties on anyone who performed an abortion due to Down syndrome, and another that would criminalize some methods of surgical abortion—we received an email from one of his colleagues saying, “I absolutely positively did not. They are ridiculous bills.”

The colleague then followed up with an email that said, “Just so you are aware, the characterization of the bills as ridiculous in my previous email is mine, not Mr. Cassidy’s. He had nothing to do with either of those bills.”

Farce aside, state legislators have condemned Cassidy’s continued activity in South Dakota, especially in light of his questionable financial track record.

“It’s a disgusting situation that he comes out here and interferes in South Dakota’s legal system, trying to ‘save women,’ when he can’t manage his own affairs,” Gibson said. “Harold should stay in New Jersey and manage his own affairs.”