Of #FastTailedGirls and Freedom

Like a lot of others, I was a "fast-tailed girl" before I really understood what those words meant.

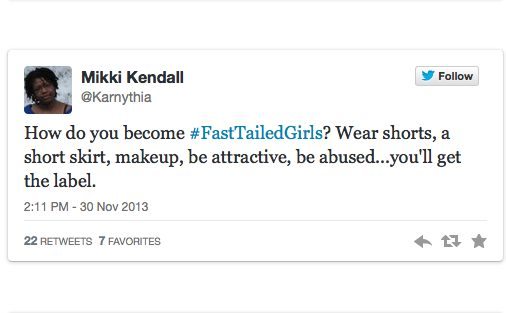

When Hood Feminism started the #FastTailedGirls tag on Twitter Saturday, thousands of women came together in an outpouring of emotion. Like a lot of others, I was a “fast-tailed girl” before I really understood what those words meant. It’s one of those colloquialisms you hear as a child in certain communities that is half warning, half pejorative. For those who weren’t raised in the same cultural context, to be a fast-tailed girl is to be sexually precocious in some way. You are warned not to be a fast-tailed girl, and also not to associate with fast-tailed girls. Sometimes it is shortened to “fast,” but either way it is presented as a bad thing. Often the elders who use the term are attempting to protect young women from being perceived as Jezebels. When you consider the long history of sexual violence perpetrated against Black women in the United States, the roots of this particular aspect of respectability politics are easy to grasp.

However, it is a deeply flawed response to the problem. Why? Well you don’t actually have to be sexually precocious to be labeled a fast-tailed girl. Perception is everything, and so a host of perfectly normal, age-appropriate behaviors—like talking to boys, wearing shorts or makeup, or even going through puberty early—are enough to convince some people that you’re headed for trouble. And once that perception is entrenched, any bad things that happen are automatically the victim’s fault. Like other expressions of the Madonna/whore complex, there is an idea that bad things don’t happen to good girls.

Research from the past decade by the Black Women’s Blueprint and the Black Women’s Health Imperative shows that some 40 to 60 percent of U.S. Black girls are sexually abused before age 18. Those girls are likely to be labeled fast-tailed retroactively by people who need to believe that what happened to them was their fault; they must have done something to entice a man’s interest, so abusers get a free pass. This was evident when R&B singer R. Kelly, who when he was 27 married the then-15-year-old performing artist Aaliyah, was allegedly caught on film urinating on another teenager; his subsequent trial on child pornography charges wasn’t enough to end his career, much less affect his freedom. Kelly’s ability to avoid consequences is unsurprising. Often it is easier for communities to focus on the girls in such cases than on potential predators.

My grandmother warned me at length about being fast, and about hanging out with fast-tailed girls over the years that I lived with her. When I moved in with my mother at age 12, I learned that a pubescent body was enough to make me fast in the eyes of some people. I was something of a tomboy, despite family efforts to turn me into a little lady, and while the lectures from my grandmother remained the same, my mother made the term into a pejorative. When a man stared at my suddenly prominent nipples on a windy day, I got into trouble for being fast. I never told her about the old family friend (emphasis on old—he wasn’t much younger than my grandfather) who started hitting on me long before our miniskirt battles, or about the babysitter who molested me and whose nickname for me still makes me nauseous.

What my mother saw as me being fast-tailed was a survivor struggling to figure out my own sexuality without someone else’s input. Because everything I did was already wrong, I was convinced I couldn’t tell her—that she would see it as my fault, much the way she interpreted my blossoming body as invitation to grown men. Our already strained relationship deteriorated further over the years that followed, as my body and my interests developed past the boundaries of what she deemed acceptable. Clothes, friends, even phone calls were battlegrounds for a war with no winners and no hope of resolution.

As an adult, I can look back and see my mother was probably afraid for me, because I was so far from her idea of a respectable young lady. I hung out with boys, wore midriff-baring shirts and miniskirts when I could, and practiced flirting like some people breathe. I wasn’t Jezebel or Lolita, but she couldn’t see that, and I didn’t have the words to explain that I was fighting to control my own body. For young Black American girls, there is no presumption of innocence by people outside of our communities, and too many inside our communities have bought into the victim-blaming ideology that respectability will save us. The cycle created and perpetuated by the fast-tailed girl myth is infinitely harmful, and so difficult to break. But, as we came together online and in some cases offline, healing occurred. People reported feeling a sense of catharsis, and many pledged to stop perpetuating these toxic ideas. Sometimes just knowing you aren’t alone is enough to alleviate the shame these concepts can make you feel. The great thing about “hashtag activism” is how much easier social media makes it for people to reach out to each other, to be able to see that they are not alone, and to begin conversations that may be too difficult to broach for the first time in person.

Obviously, the problem isn’t going to be resolved by a hashtag, or by a few thought pieces. But the first step to finding a solution is admitting that there is something to be fixed. We’ll need to keep having these conversations, keep being open to the idea of working against these socially ingrained notions so that we can stop them. The problem is not unique to Black communities, to the cisgendered, or to heterosexuals, but as with every other community it touches, the internal work must be done so that the external problems can be addressed. This is a sickness that touches so many, and we need to work as partners with each other to heal it. But this is not a call for outside assistance; this is a message for those outside our communities to address the racialized misogyny in their communities that perpetuates the idea of Black women as Jezebels. Any solution to this problem will require society to address all the racist, sexist tropes that frame women of color as sexually available and unrapeable. If we are all to be free, we must all be willing to stand against rape culture no matter how it is expressed.