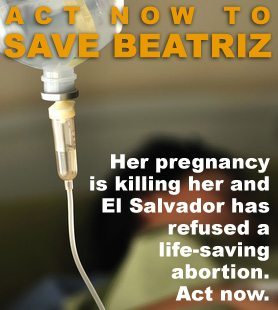

In El Salvador, Yet Another Woman’s Life Subordinated to Non-Viable Fetus

A 22-year-old Salvadoran woman with severe chronic medical conditions is pregnant with a fetus without a brain. But a 1998 law in El Salvador prohibits all abortions, without exception.

See all our coverage of Beatriz here.

Petition the El Salvadoran President and Supreme Court for Beatriz’s life here.

Beatriz wants to live. A 22-year-old Salvadoran from a poor, rural community, Beatriz (a pseudonym to protect privacy) suffers from chronic and severe medical conditions. She is the mother of an infant. And she is roughly 18 weeks pregnant with an anencephalic fetus, a fetus without a brain. Doctors at the Maternity Hospital determined that the pregnancy is life-threatening, and Beatriz requested that Salvadoran medical personnel perform an abortion, but a 1998 law in El Salvador prohibits all abortions, without exception.

The Salvadoran feminist organization Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto Terapéutico, Ético y Eugénesico (Citizen Group for the Decriminalization of Therapeutic, Ethical and Eugenic Abortion), which has been working to decriminalize abortion in the country since 2009, petitioned the Salvadoran Supreme Court on April 15 to intervene and to direct medical personnel to provide without fear of criminal prosecution the procedures Beatriz needs to save her life. Under current law, both Beatriz and any medical personnel involved in an abortion would face criminal charges and prison time. The court responded with a temporary directive that medical personnel provide the care necessary to guarantee her life and health while they make a decision regarding the petition for an abortion. Medical personnel were also directed to present to the court within five days a report on the condition of the mother and the fetus to inform their deliberations.

Within the past few days Amnesty International has initiated a petition asking for life-saving medical care, including an abortion; the United Nations has spoken; and the Salvadoran Minister of Health, Dr. Maria Isabel Rodriguez, has requested that the Supreme Court approve the request. Dr. Rodriguez emphasized that Beatriz’s kidney function continues to deteriorate as the pregnancy advances, and that the public health system is ready to perform an abortion. The Salvadoran Attorney General for Human Rights also supports the request.

At a press conference the Agrupación convened in San Salvador on April 18, Esther Major, an Amnesty International representative in El Salvador, characterized the way Beatriz is being treated as “nothing less than cruel and inhuman.”

“While we are talking, while the Court is thinking and the government is delaying, Beatriz is suffering. … The Salvadoran government has clear obligations, international as well as domestic, to protect Beatriz’s life, and to assure that Beatriz can access vital treatment as soon as possible.”

Legal reforms in 1998 in El Salvador, promulgated by conservative religious forces, outlawed abortion without exception. Previously it was permitted if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest, the mother’s life was in danger, or the fetus was not viable. In addition, a constitutional amendment was added declaring that life begins at conception, which means that prosecutors can charge women who seek abortions with aggravated homicide, punishable by 30 to 50 years in prison, rather than the lesser crime of abortion, which carries a term of two to eight years.

Threats of prosecution and prison terms are not to be taken lightly under the 1998 law. The Agrupación has mounted legal and educational campaigns to secure the release of six women from prison. Since no comprehensive data exist in the country, the Agrupación is conducting its own research, which reveals that currently at least 24 women are serving prison terms of up to 40 years for abortion or aggravated homicide related to abortion charges.

The Sí a la Vida (Yes to Life) Foundation, an anti-abortion religious organization, expressed its belief that feminist groups are exploiting and manipulating Beatriz in order to legalize abortion in the country. An opinion column in the Salvadoran press on April 17 pleaded with Beatriz, “Don’t kill it!” while obscuring the fact that the fetus is anencephalic and cannot sustain life outside the uterus, using language such as “you are expecting a baby that might be born sick.”

Beatriz waits as the Agrupación works through the restricted avenues available to save her life and perhaps create fissures in the wall of political and religious opposition to the decriminalization of abortion even under limited circumstances for women in the country. For Beatriz, the eyes and voices of the world constitute her hope for life.

Beatriz is not the only woman for whom death looms as a highly possible outcome of pregnancy. Since all abortions are illegal in the country, they all take place in clandestine conditions. The Agrupación’s as-yet-unpublished research from 2010 and 2011 finds that perhaps 35,000 unsafe abortions (as defined by the World Health Organization) take place every year in El Salvador.

As in the death of Savita Halappanavar in Ireland in 2012, Beatriz’s life could also be subordinated to that of a non-viable fetus. Although El Salvador refers to itself as a secular nation, the Catholic Church, conservative evangelical churches, and groups such as Sí a la Vida wield overwhelming political power and influence.

Beatriz’s situation becomes the most recent and most urgent of the many the Agrupcación has addressed. The long-term goals of the group focus on substantial reforms to the country’s draconian abortion law. In addition, since 2009 the Agrupación has organized legal and public education campaigns to gain the release of six women who were serving prison terms of up to 30 years for the “crimes” of abortion or aggravated homicide related to abortion. The group continues to work on the release of at least 24 more women still in prison, according to the research they have done. As the Agrupación gathers data on women who have been formally charged with abortion or aggravated homicide, a clear pattern emerges of the selective prosecution of young, poor, rural women. In addition, court documents in numerous cases reflect obvious medical, prosecutorial, and judicial errors or negligence. In several of the cases where women regained their freedom from prison, appeal processes revealed that no evidence that an abortion occurred or was provoked by the woman was ever presented in court, and in some cases evidence demonstrated that the fetal death resulted from natural causes and was not caused by the woman. Money speaks, and if Beatriz had the financial resources, she might have been able to secure appropriate health care in a private facility where she would have a greater probability of receiving life-saving treatment without fear of imprisonment.

Beatriz’s life is threatened by her health conditions and a high-risk pregnancy. However, the deeper threats come from an intractable and misogynistic political and religious system which criminalizes women for being young, poor, rural women. Right now the eyes and voices of the world constitute Beatriz’ hope for life. She wants to live.