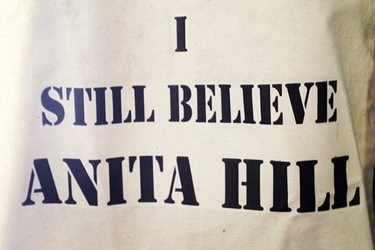

How Gender Justice Has Evolved Since the Days of Anita Hill

Today, more than 20 years after Hill first came on the national stage, we better understand that gender justice is not only about women's rights in opposition to men and their privilege—it encompasses the full spectrum of gender and sexuality.

As part of the new Anita Hill Lecture Series, I recently gave a lecture in which I explored how feminism and gender justice relate to the notion of sexual rights, and why this relationship is important. Today, more than 20 years after Hill first came on the national stage, we have a clearer understanding that gender justice is not only about women’s rights in opposition to men and their privilege. Gender justice is increasingly understood to encompass the full spectrum of gender and sexuality, as different people experience these. We now regularly see the rights and needs of gay men, lesbian women, and trans people as part of a feminist analysis. And we talk more and more about how traditional notions of masculinity are harmful to men as well as women. Sexual rights is rooted in the idea that sexuality needs protection and space in the world, which expands the gender justice conversation beyond where it was in 1991.

Like many individuals, I was riveted by the coverage of the Anita Hill hearings, both because Hill profoundly affected my thinking on gender, race, and sexuality at a time when I was grappling with feminism and what it meant in my life and career, and because I admired that she used her courage and voice at great personal risk to herself. With many women being attacked for pushing the envelope on issues of gender justice, it’s important to remember that advocacy, at its core, is about bravery.

In my advocacy on issues of gender-based violence, I have always worked to balance a recognition of the pain and trauma of sexual violence with creating the space for survivors to own their sexuality as they seek economic opportunity and find their own voice. For me, gender justice is an equation of gender, sex, money, and rights, and how these facets intersect with each other. It made sense to examine this in the context of sexual violence, because power dynamics are so clearly implicated in this issue, as they were around workplace sexual harassment when Hill first spoke out.

It’s increasingly important to expand ideas of women’s rights to include larger issues of gender, gender identity, and sexuality, for a number of reasons. First, it’s crucial to recognize that the rights of women are not gained in isolation, and to build on the history in feminism of working toward understanding the intersections of gender, race, and class.

Second, we are understanding more and more that men too have gendered experiences, and these experiences affect their human rights, as well as the rights of women. Oppressive myths around race and masculinity have resulted in discrimination against African-American and Latino men in the criminal justice system.

Third, activism around gender identity and the rights of transgender people has highlighted crucial aspect of rights around gender and how we perceive and experience it, questioning what we mean by the term “gender” at all.

Fourth, the long-bubbling theory of sexual rights—meaning our human rights as they relate to all aspects of our sexuality, from sexual orientation to sexual violence to the rights of all of us to assert and own our sexuality—brings another dimension to questions of gender justice.

Finally, expanding on traditional conventions of women’s rights means we take to heart the understanding that so much of the subjugation of women and construction of gender roles is rooted in women’s real or perceived sexual power and in sexually related behavior. This is important because it allows us to more explicitly identify and name the problems we seek to solve. Expanded views of gender justice allow us to broaden our collective world view and connect as people who strive to achieve human rights for all. In the context of sexual violence, this approach acknowledges that violence harms and is corrosive for all of us, not just women and girls.

Unfortunately, we still face challenges in that there is little agreement regarding how we solve these issues and create a world that values equality, dignity, and justice for each of us. This is particularly true in cases of sexual and gender-based violence. Current policy efforts focus on an idea that people, especially women, are inherently vulnerable or make bad individual decisions. We need to treat these issues as systemic problems and focus on root causes and collective action—asking questions around the societal, systemic, and policy factors that create the conditions we seek to change and insisting on money and funding for preventive, treatment, and cultural programs that work. This approach is important whether we are talking about sexual assault, sexual harassment in the workplace, or trafficking people. It has been much-discussed in the wake of the juvenile court trial in Steubenville. Ultimately, it is solutions based on collective power and change, and a positive role for government, that will address the deep-seated conditions that allow sexual violence to thrive. Hill brought much of this to light in 1991. This conversation is especially timely since Hill is currently the subject of a new documentary that brings her story and its legacy to new audiences. Looking back and building on her work shows us how far we’ve come, but also lights a path forward for the future.