Eisenstadt v. Baird: The 41st Anniversary of Legal Contraception for Single People

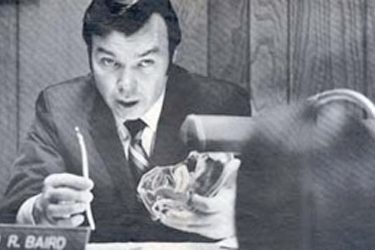

On the eve of the anniversary, Rewire spoke with William Baird, from the landmark Eisenstadt v. Baird case, about his reproductive health efforts past and present.

March 22 marks the 41st anniversary of Eisenstadt v. Baird, the Supreme Court decision that established the right of single individuals to possess contraception. That’s right: As recently as 1972, you could go to jail for giving contraception to an unmarried person. And William Baird did. Eight times. In five different states.

On the eve of the anniversary, Rewire spoke with Baird about his reproductive health efforts past and present.

Bill Baird attributes his birth control crusade to having seen a 29-year-old mother who already had numerous children die in a Harlem hospital after she tried to self-abort with a coat hanger. She didn’t have the right to a legal abortion, and she didn’t have the right to contraception, or even information about it. Baird dedicated his life to providing contraception and abortion care to women, particularly poor women, and to challenging the laws that denied these things to them.

In 1965, Baird was arrested for distributing contraceptives in New York; in 1966 he was arrested in New Jersey. The trials that resulted led to the reformation of those state’s laws.

In Massachusetts in 1967, it was illegal to both exhibit contraceptives and distribute them to unmarried persons. Seeking to challenge the law by breaking it once again, Baird gave a lecture to approximately 2,000 students at Boston University. He displayed contraceptives during the lecture and closed by giving contraceptive foam and a condom to a young woman. He was arrested and subsequently convicted of both crimes.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court unanimously set aside the conviction for exhibiting contraceptives as a violation of Baird’s First Amendment rights but sustained the conviction for giving away the foam. In Massachusetts, fornication was a misdemeanor punishable by a $30 fine or three months in jail; distributing contraceptives was a felony punishable by five years in prison. Baird spent 36 days in Boston’s Charles Street Jail, where the conditions where so bad that a court later found them unconstitutional: “It scarred me to this day,” Baird told Rewire, “but I endured it.”

In 1965, the Supreme Court had held that Connecticut’s prohibition against the use of contraceptives was an unconstitutional infringement of the right to marital privacy. But that decision, Griswold v. Connecticut, wasn’t much help to single people or people like Baird willing to help them. In Eisenstadt v. Baird, Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. wrote, “the marital couple is not an independent entity with a mind and heart of its own, but an association of two individuals each with a separate intellectual and emotional makeup.” That is not how the law treated marriage historically. Married women were once considered the property of their husbands, rather than separate persons. In holding that prohibiting contraception only for unmarried people denied them the equal protection of the law in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, the court recognized the individual autonomy of women. The case was important to the court’s decision in Roe v. Wade the following year.

Baird continued to fight openly and aggressively for reproductive rights, and Eisenstadt wasn’t his last trip to the Supreme Court. But his fight came at great personal cost. Many of the women’s rights leaders of the time rejected him. His clinic was attacked. He became estranged from his wife and children, who endured threats and vilification. Today he is “eighty and going blind and broke,” as he says. Because he is blind in one eye and losing sight in the other, his second wife, Joni, reads him his email and news of the fight for reproductive and sexual equality. He said it amazes him “how the body wears out but the mind fights on.” He continues to lecture on college campuses. Of a recent talk, he said, “These kids could not believe I faced a ten-year jail term for their right to have sex protected.” He said that his granddaughter thinks he “murders babies,” but his stepsons know what he does and has done and love him for it.

Baird is as fiery and eager to talk about the struggle as ever. He continues to be dismayed by individuals who would infringe on the right of women to make their own decisions. When I spoke to him yesterday, he recited a section of Eisenstadt v. Baird from memory: “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.” That right is young—and still under attack.