With New Evidence in Hand, Texas Lawmaker Files Bill To Eliminate Waiting Period For Abortion

Citing new research showing that Texas' increased restrictions on abortion are negatively affecting women, family planning clinics, and abortion providers in the state, Rep. Jessica Farrar will file a bill this week to overturn the forced 24-hour waiting period.

Citing new university-led research showing that Texas’ increased restrictions on abortion are negatively affecting women, family planning clinics, and abortion providers in the state, Rep. Jessica Farrar will file a bill this week that would overturn the forced 24-hour waiting period between an ultrasound and an abortion procedure, originally passed into law in 2011.

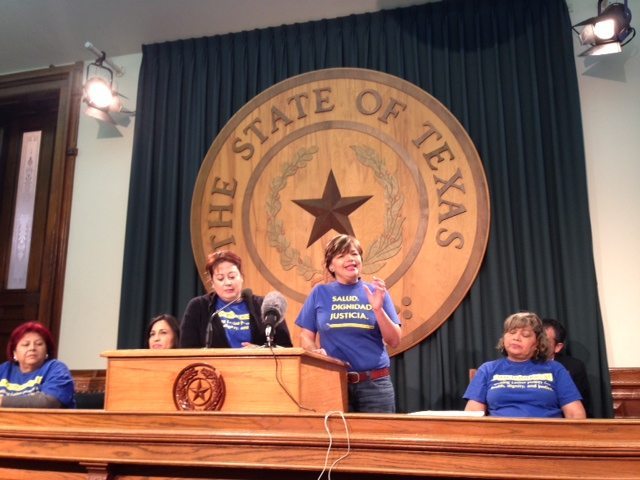

“The waiting period does nothing but add extra [burdens] to a woman’s ability to make a well thought-out decision,” said Rep. Farrar at a press conference this morning at the state capitol. “The legislature needs to step away and allow health care professionals, who are trained, to make those decisions with women.”

The mean travel distance for Texans seeking safe abortion care to the nearest provider is 42 miles each way (though some travel as far as 400 miles each way), and Texans spend an average of $146 in out-of-pocket expenses—costs other than medical fees—to get safe, legal procedures, said representatives from the Texas Policy Evaluation Project (TPEP), an ongoing three-year study that evaluates the effects of a two-thirds cut to family planning funds enacted in the 2011 legislative session.

The TPEP found that while “there has been a decline in the number of women who obtain abortions” in Texas since HB15 passed, that decline is not due to a decreased need or desire, but to an increase in logistical and financial hurdles. In other words: women who already cannot afford to take off work, to travel long distances to doctors or to pay for out-of-pocket expenses related to their procedures are being forced to continue unwanted or unplanned pregnancies. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission has projected an increase of 23,760 births in 2014-15 due to reduced access to state-subsidized contraception, at an additional cost to taxpayers of up to $273 million.

But TPEP has been looking at the impact on individual Texans in real time. Over the last year, TPEP surveyed 318 women seeking abortion care, as well as “several large clinics.” Their findings show that the largest deterrent over the past year for Texans seeking safe, legal abortion care has been the forced 24-hour waiting period, which requires patients to make two visits to their doctors, a visit first for a forced ultrasound and a second 24 hours or more later for their procedure.

“These regulations with HB 15 do not positively impact women’s decision-making,” said Dr. Daniel Grossman with the TPEP, “and in fact are burdensome for women.”

What wasn’t a factor in deterring Texans from getting abortions? The required viewing of a forced ultrasound before their procedures. Eighty-nine percent of women surveyed by the TPEP said that even after being made to view the ultrasound image, they were as confident as ever about their decision to end their pregnancies.

Farrar was joined at today’s press conference by activists with the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health (NLIRH) and women from Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, who said they hardly needed a university study to tell them that women in Texas are no longer getting the family planning and reproductive care they need.

“We know exactly what the problem is when funds are being cut,” said Lucy Felix and Lorena Singh, speaking in both English and Spanish. “Nobody has told us. We live it.”

According to the TPEP, 53 family planning clinics in Texas have closed as a result of the 2011 budget cuts that were meant to specifically target Planned Parenthood, though only a handful of that organization’s clinics have shut down. The cuts have predominantly affected independent clinics and those that rely more heavily on public funds than did Planned Parenthood.

The Valley has been particularly hard hit by cuts that drastically reduced their access to low-cost reproductive health care, as evidenced in interviews with 185 women in the area conducted by the NLIRH and the Center for Reproductive Rights, which also released preliminary findings at the press conference today.

“Either I pay the rent and give my children a place to live,” a woman named Nancy from Edinburg, Texas, told researchers, “or I have a mammogram, a Pap test, or contraceptives. It’s one or the other, but not both.”

Rep. Farrar said she “wouldn’t be having to stand here today” if Texas legislators spent more time focusing on improving, not reducing, access to family planning, “because it would drastically reduce the need for women to have abortions.”