HPV and Things That Go Bump: Time for Action on Genital Warts

While we await the expected and demonstrated good news of few cervical and other cancer deaths among person immunized against HPV, a recent study from Denmark already shows us that vaccination can significantly reduce genital warts.

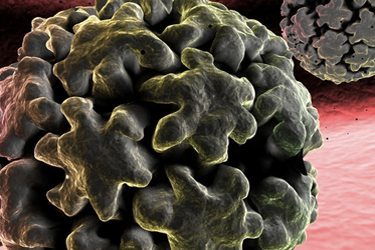

Last year, my organization, the National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD) increased our focus on disease caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. And while much deserved attention has been paid to the critical outcome of cervical cancer, we also decided to tackle the more frequent clinical outcome of HPV infection—genital warts. Those unsightly, bumpy, cauliflower-like growths that go by the more clinical term condyloma.

Long considered more an unsightly and anti-erotic nuisance because genital warts are not life threatening, they do play a role in the spread of HPV by increasing the shedding of virus and for anyone who’s ever had them—especially when they are invasive—they are more than just a nuisance. Sexual health is more than the absence of disease, so preventing and treating genital warts should be part of our collective efforts. And from a primary prevention perspective, it syncs up directly with eliminating cervical and anal cancers.

While reducing genital warts and cervical and anal cancers is key from a public health standpoint, we decided to look more closely at genital warts from a business perspective. Namely, as public health entities that offer STD clinical services—many of NCSD’s own members—seek to diversify sources of revenue to keep their doors open, getting reimbursed for treating a common STD seems like a way to bring in additional revenue. Diagnosing genital warts doesn’t require much more than a glance from a provider and speedy, in-office treatment is readily available. In addition, patient-applied products have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) making treatment even more accessible.

In our scaled up work, we also discovered that genital warts are such a common reason for a visit to a public heath STD clinic that as clinic resources, staff, and hours of operation have been cut back, some clinics no longer see genital wart patients. I was at first a bit stunned by this disclosure, but the reality became clear when one provider said: “If we see all the wart patients, we don’t have the time to see the gonorrhea and chlamydia patients or their partners.” Point taken. But what if those turned away patients could generate streamlined revenue due to easy diagnosis and treatment? It seems to meet multiple needs: public health outcomes, individual patient outcomes, and adding some new revenue to aid dwindling discretionary monies from government.

So while we pursue diagnosis and treatment of genital warts in public health clinics, we can also turn to primary prevention. Most genital warts—as high as 90 percent of all cases—are caused by two types of HPV, 6 and 11. These two types are among the four types covered by Gardisil, one of the vaccines widely available and approved by the FDA. A study from the British Medical Journal found 82 percent of genital warts are prevented by Gardisil.

Yet, uptake of HPV vaccines in this country remains appallingly low, particularly in the South. In Mississippi, less than 20 percent of adolescent females received all three doses of an HPV vaccine according to the 2011 National Immunization Survey. In Arkansas, only 15.5 percent of adolescent females received all three doses; and in South Carolina, only 23.3 percent.

While we await the expected and demonstrated good news of few cervical and other cancer deaths among persons immunized against HPV, a recent study from Denmark already shows us that vaccination can significantly reduce genital warts.

The February 2013 issue of the journal Sexually Transmitted Diseases highlights a study from Denmark showing the country’s national HPV vaccination program has had a huge impact on reducing genital warts. Since 2009, Denmark has provided Gardisil to all 12-year-old girls and also to those up to age 15 since 2008 as a “catch-up” vaccination. According to the study’s authors, the vaccination program turned the corner on continued increases in new genital warts cases—for women on an average of 3.1 percent fewer cases each year. Moreover, for those young women vaccinated and coming of age—now 16 to 17 years old—genital warts were “virtually eliminated”.

Finally, NCSD has developed a brochure for providers on talking about genital warts that has a great deal of information that might be useful. You can find it here.

Focusing on genital warts is in the best interest of patient and public health, as well as a good way to bring in money in an era of dwindling resources. The Danes are telling us something and we should be listening… and acting.