Understanding the Girl Effect

A recent opinion piece in The Guardian questions the contributions that girls and young women can make to economies when they delay childbirth. The author fails to understand the complexity of the "Girl Effect."

Recently, The Guardian’s Poverty Matters Blog posted an opinion piece by Dr. Ofra Koffman that questions the contributions that girls and young women can make to economies when they delay childbirth. Koffman argued that the so-called “Girl Effect” of delaying childbirth does not necessarily “stop poverty before it starts,” as the Department for International Development (DFID) claims.

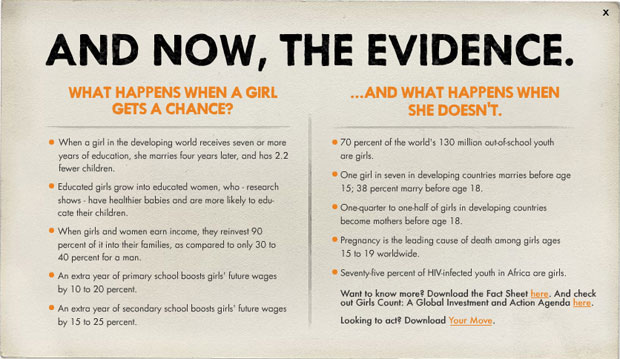

However, the “Girl Effect” is about much more than adolescent fertility. It’s about the holistic approach to harnessing the power of girls and women—from literacy to the elimination of death in early childbirth to leadership opportunities—and how these factors come together to reduce global poverty.

The ability to choose if and when to have children is a huge piece of the puzzle to the “Girl Effect,” but it is not the only piece. When a girl can plan when to have children, how many, and how far apart they are spaced, she is then able to take advantage of educational opportunities.

According to the World Bank’s 2012 World Development Report, studies show that when women have access to education, there are positive health benefits for their children—including lower mortality, better nutrition, and higher immunization rates, among others. In Africa, children of mothers who have received five years of primary education are more likely to live past the age of 5. In India, among other countries, the World Bank found that the more income a woman earned, the more schooling her children received. Research also shows that women are more likely than men to invest income back into their communities, spending their resources on nutritious food, medicine, education, and family needs.

The global picture of girls’ and women’s health is not always as it appears.

Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Burma, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco are cited as examples of lower-income countries that have lower rates of adolescent fertility than the U.S. The author uses these countries to indicate that early childbirth and economic standing are not connected, and to show that low birth rates do not equal high incomes for these countries. However, these examples are not representative of all developing countries. In Niger, Nepal, and Venezuela, for example, the adolescent fertility rates are more than double that of the U.S.—and more than triple that of the U.K. In these three developing countries, the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth is higher than in both the U.S. and the U.K. combined.

In addition, giving birth presents numerous health challenges to adolescent girls in developing countries, where pregnancy and childbirth are the leading causes of death for girls 15–19 years old. In Rwanda, cited as having slightly higher fertility rates than the U.S., there are a staggering 540 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births, as compared to 15 per 100,000 deaths in the U.S. For every one of these deaths, at least another 20-30 women suffer serious illness or disability from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes.

Young girls are particularly vulnerable, as they often lack access to information and services relating to family planning, safe delivery, and pre- and post-natal care. In developing countries, where health systems can be fragile, delaying childbirth can be the choice between life and death.

The author further argued that the U.K. government’s efforts to reduce poverty failed because “a certain proportion of young women want to become mothers.” Ultimately, for many girls and women in the developing world, no one has ever bothered to ask them if they want to be mothers. There are 215 million women around the world who have an unmet need for contraception. And every year, an estimated 10 million girls under 18 are married, whether they want to be or not. Half of all the world’s child brides live in South Asia, and while each girl may only have a few children, that does not indicate that any of their pregnancies were their choice, nor does it ensure that they are safe, healthy, and empowered.

The “Girl Effect” is an amalgamation of exactly these three components: security, health, and power.

When childbirth is delayed, there is a domino effect of positive outcomes. Girls grow up educated, armed with information on how and where to secure quality health services, and the strength to stand up for their autonomy. When this happens, the people they encounter view them as powerful forces of change. In isolation, these results may not be able to end poverty; but as a whole, they have the incredible power to transform our world, one girl at a time.