Reflections on Standing Rock and Our Queer Mother Earth

Nearly two years have passed since my trip to Standing Rock soon after the October 27 raids. I had been publishing about the Dakota Access pipeline for a couple months, but physically being in North Dakota was a different beast.

Editor’s note: The author delivered an earlier version of this essay at the Our Queer Mother Earth Outwrite DC event on June 9.

I have many identities that shape who I am and the work I do. I’m openly bisexual and Two Spirit. I’m multiply-disabled with chronic pain and mobility impairments. I’m a mixed race Tsalagi and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. I’m also a journalist, educator, community organizer, and water protector. It was these many identities that took me to Standing Rock to stand on the front lines alongside my relatives to fight the Dakota Access Pipeline in November 2016.

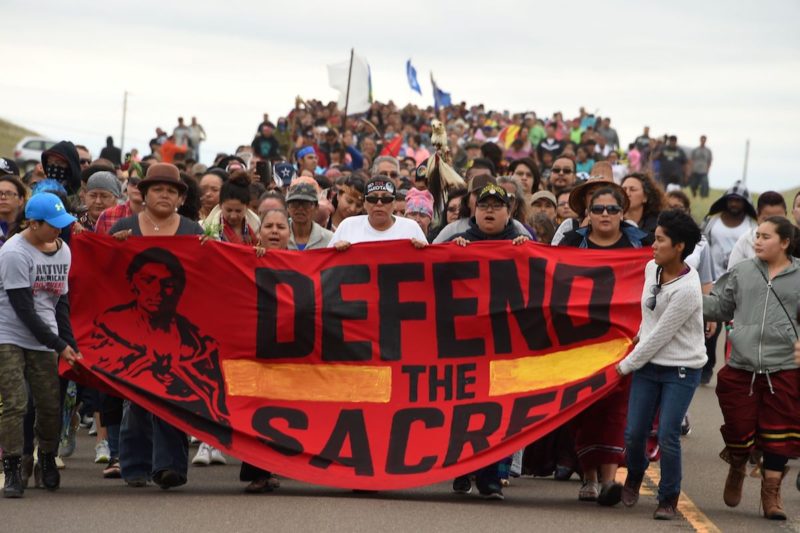

While DAPL is harming our Mother Earth, it is more than a mere pipeline. It is another example of our tribal sovereignty being stepped upon. It is the breaking of our treaties. It is the continuation of over 500 years of our genocide.

The government and corporate assaults on the Standing Rock Sioux Nation and the water protectors have been so vile, so violent, that I’m often at a loss for words to properly describe how I feel and what my personal experiences were like. This is my attempt at sharing my first few days at camp and how I’ve been forever changed.

My first day at the Oceti Sakowin camp was a baptism by fire. I arrived around 10 p.m. on November 1. I drove down Flag Road looking for the Two Spirit Camp, with only the rainbow flag as my beacon in this unknown place. Upon arrival I stepped up to the fire where about ten people were gathered to introduce myself. The greeting I received was less than friendly. I had one contact at the camp, and they didn’t seem too eager to have me there. To add to this, none of the other queer water protectors would even say “hello” to me. I did receive a collective groan of disgust, though, when I mentioned I’m a journalist.

I didn’t expect the red carpet, but the response I received was a far cry from the experiences my Two Spirit friends described. Yet I was determined to stay. I now understand that the Two Spirit Camp was in a tough transitional period, and many people were suffering from the October 27 raids on the Treaty or North Camp and didn’t take too kindly to strangers, but this sadly set the tone for much of my time there.

Around 5 a.m. on November 2 I heard a man over the loudspeaker telling us all to wake up, that we weren’t on vacation, and that our ancestors needed us. I groaned, covered my head with a pillow, and tried to sleep for another hour because I know my ancestors want me well rested.

After a night of poor sleep, I attended the new camper meeting and then went to the media tent to check in. I was finishing my breakfast on “Media Hill,” also affectionately known as “Facebook Hill” because it was one of the few spots with cell reception, when a jeep full of Native campers screeched to a halt in front of me. They yelled out to me and a few other people, “Are you journalists? They’re macing and shooting people at the water. We need you there now.” I still wasn’t clear on the camp rules for journalists, so I hesitated and replied that I hadn’t checked in yet. They screamed back, “Go!”

My peaceful morning of learning the camp and meeting people changed in an instant. The best-laid plans often changed quickly there. I hopped in the back of the jeep and headed to the Cantapeta Creek, where the grave sites of two Standing Rock Sioux women were. I didn’t have my frontline bag on me with my camera gear, but more importantly I was without my mask, bandanna, and goggles to protect against chemical attacks. I thankfully had my phone and inhaler though. I had no naive ideas of what the law enforcement would be like. I knew this was a war zone and that things would only become more violent as the then–January 1 deadline for oil pumping approached.

The jeep soon screeched to a halt in front of the creek. We all jumped out and I was on my own. I took a deep breathe, looked around for a moment, and charged to the creek. This is all still a blur to me, but I continue to feel that day in my body. The fear, anxiety, and righteous rage. I remember our people swimming and boating across to the other side of the creek where they stood in the frigid water, peacefully with hands in the air, while law enforcement sprayed them at point blank range with large fire extinguisher–like canisters of mace. It reminded me of one of the Black Lives Matter marches in Boston, when I was at the police line staring the officers in the eyes, with my hands in the air, yelling, “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!”—only this time the officers weren’t listening, and the only screams were for more reinforcements to help the injured.

I had been publishing about Standing Rock since September 2016, but physically being there was a different beast. I can still vividly hear the helicopters flying low over my head and the drones circling above like insistent gnats that I couldn’t swat away. I later learned the drones belonged to our people, who were documenting law enforcement brutalities and DAPL abuses, but at the time I wanted to take a baseball bat to them. Helicopters still make me flash back to that day.

I was trying not to break down and sob or scream. I stayed calm, but the rage and pain were simmering just below the surface. I thought of my ancestors and what they endured for me to be there at that moment. I cried a few tears for the terror, agony, and rage that they must have felt during the Trail Where They Cried. I then sucked it up for them and did my job.

I filmed all of this on my phone while I attempted to give context to a place I had literally just arrived at 12 hours earlier. I wanted to be in the water with my relatives. I wanted to do more than simply film and photograph these atrocities. How could I just watch them being hurt? What kind of a person, what kind of Native does that? Because of my health problems I knew I couldn’t go in the water. If I was directly maced, it could kill me. I couldn’t do anything that would put others at risk because they had to care for me. Instead, I stayed back and filmed my people being abused.

At one point, the wind shifted and moved the mace in my direction. My lungs burned an indescribable pain, then they seized up and seemingly refused to work. I hit the ground unable to breathe. It was as if I was having 37 years worth of asthma attacks all at once. It felt like genocide. I remember panicking and grabbing for my inhaler and using it repeatedly. I wouldn’t ask for a medic and take attention away from our injured warriors, but I was petrified.

I had traveled to North Dakota alone, and other than my one less-than-friendly Two Spirit contact, I didn’t know a soul there. I hadn’t checked in with legal yet so there was no paper trail of my presence either. If something happened to me, my only hope of anyone looking for me would be my editor, publisher, and a few loved ones I did daily check-ins with, but they were all over a thousand miles away.

As I was doubled over trying desperately to breathe, stay calm, and not think about how 4,000 of my ancestors, one-third of our then-total population, were killed by the very government that could kill me now, a fellow water protector, Chad Charlie, came over to check on me. Just that 10-second interaction helped calm me down enough to be able to go back and get more video. I never had the chance to thank him for that.

Later that night, back at camp, I was amazed at how life went on as if that trauma hadn’t occurred. Yes, people were hurt and that was being acknowledged, but there was still laughter, drumming, and singing. We were doing what our ancestors had done before us. We were finding hope in the hopeless. One battle didn’t stop anyone in that camp. The horror stories that I heard from our women and Two Spirit relatives who were arrested were despicable beyond words, and would send most people running home, but our women and Two Spirit people persevered. What choice did we have? This is our land. This is our home. We have to defend it for the seven generations to come. The colonizer has already taken so much from us. They can’t take anymore.

A few days went by and I began to learn the land, camp politics, and life. Winona’s Kitchen was one of my daily stops, because regardless of the time of day there was always hot coffee and food available and a warm smile and kind words from Winona. I would usually say “hello” and chat for a minute, and then zoom off eating my food while walking to my next destination.

I spent most of my time in North Dakota trying to get people to talk with me. Even basic conversations became difficult when other Native people learned I was a journalist. It was like pulling teeth to get people to talk with me on the record. After seeing how some non-Native journalists behaved though, and with my light skin, I can understand my people’s hesitation. It still hurt though. I’d like to think that I’m honorable and work with integrity, but trust was in short supply.

I often spent time on Media Hill trying to learn when actions would go down and offer my help. It was one of the few spaces I felt mostly welcome in, but I couldn’t help but notice that most of the media folx there read as able-bodied, het, cis men. I know we had plenty of other indigenous women journalists at camp, and I’m sure we also had more queer members of the media and people with disabilities present, but to this day I have yet to meet any of those people. I was often fighting my way through a sea of able-bodied, white, cis men with more money and supports and much better cameras and gear than I had. I knew, though, that there were stories they would never be privy to and that if I just kept at it I could earn the trust of my people.

There was another action at Cantapeta Creek on November 6. I found myself once again standing on the safer side of the creek photographing and filming as our people crossed over in an attempt to protect the grave sites. At one point, a brother was yelling for people to get in a canoe and cross over. No one would come forward. I hesitated for a moment and thought of Lakota Sioux leader Crazy Horse saying “Hoka hey,” or “It’s a good day to die,” to his people. I came forward and offered myself up. Naturally my clumsy self sunk in the mud in the creek and fell into the water. I assure you it was cold. I kept my camera in the air and told people to take the camera and that I’d be okay. A couple of people eventually helped me up and in the canoe I went. My heart was racing and I had no clue what would happen to me next.

I distinctly remember the sounds of helicopters, drones, and our people drumming and singing, and the smell of sage in the air. I joined in prayer with a new friend for a few minutes before I got to work. Just up above us on top of the hill, the police were desecrating the grave sites. They could have rushed down at any moment. Given my disabilities, I was a sitting duck. They soon began to throw tear gas our way. It burned in a way that I can’t describe. People rushed to cover the canisters as I attempted to photograph while my eyes burned and cried. Thankfully, I walked away that day relatively intact.

After extending my trip several times, I began to make plans to stay at Oceti throughout the winter. Upon learning of sexual assault within the camp, though, I decided to leave. I went there knowing there was a high likelihood of being raped, kidnapped, trafficked, or murdered by white men outside of camp, but I didn’t expect to fear my brothers. My mental and physical health were wavering, so I packed up and headed back to Washington, D.C.

Once back in D.C. on November 16, I was sick as a dog with the DAPL cough. I tried to churn out stories for the now-defunct Resist Media and keep up-to-date with the happenings in North Dakota, and I stayed glued to my phone and laptop watching videos and messaging with people. On November 20, the police launched a brutal attack on the Backwater Bridge. It left approximately 300 demonstrators injured and at least 26 people hospitalized with serious injuries. An elder went into cardiac arrest. Sophia Wilansky almost lost her arm. Vanessa Dundon, also known as Siouxz Dezbah, lost an eye.

Mariah Bruce was shot in their vaginal area. Since this assault, they have experienced extreme pain and difficulty walking. When they were rushed to the emergency room, no doctors would see them and they were sent away untreated. I surprisingly reconnected with them a year later at the L’eau est La Vie Camp in southern Louisiana. Despite their injuries, they’re fighting Energy Transfer Partners’ last leg of DAPL, the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, on their ancestral Houma homelands. This is an example of why I feel so much pride in being Native.

Law enforcement weren’t simply doing a job that night. They purposefully aimed for people’s heads, hands, and groins, and they shot people in the back as they were running away. They used fire hoses mixed with chemicals on people in subzero temperatures and laughed while doing so. This was a modern-day version of the redsk*n payment. Instead of cutting off a scalp, head, ears, hands, patches of skin, or genitals to receive payment from the U.S. government for killing an “Indian,” they simply shot us with “less than lethal means.”

As I watched the numerous livestreams in the safety of my apartment, I cried and felt ashamed for leaving. How could I leave my people and friends to endure this mass torture? I should have been there to help document the human rights violations and to help the injured. I still carry guilt with me for this. That night was one of my deciding factors to return to camp for the Army Corp of Engineers’ planned removal on December 5.

Since my first trip to North Dakota, I’ve suffered from increased CPTSD triggers, nightmares, and flashbacks, as well as increased physical pain. I was sick for several weeks with a horrible cough after both trips. I’ve also struggled with writer’s block and haven’t been as prolific in my writing and publishing. It’s been unbearable at times to write what I saw there and listen to the interviews with water protectors. If two trips totaling three weeks in North Dakota have left me with these feelings, I can only imagine how my relatives who were at camp for months are feeling.

The camps were eventually forced to close late February 2017. Since then, many of us have moved onto other pipeline and water fights. I’ve been several times to Camp White Pine in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, where communities there are resisting Energy Transfer Partners’ Mariner East 2 liquid natural gas pipeline, and made one trip to the L’eau est La Vie camp as well. I’ve collected numerous interviews and taken countless photos of our Mother Earth. All of her beauty and strength in the face of such trauma amazes me, just as the resiliency of my people does. I plan to travel more and continue this work.

Standing Rock was the beginning of a modern-day global indigenous rights movement, and I am proud to have been a part of it. The government can use its hoses and chemicals, but it will not extinguish the flame that was born there. I know many hearts are heavy, but our hearts are still strong. This genocide is not new to us. It is all too familiar. That’s what’s most heartbreaking, enraging, and inspiring. We have survived over 500 years of the white man’s torture. We will survive this too. But we deserve to thrive.