New York Attorney General Files Crucial Lawsuit Against Clinic Picketers

“The law guarantees women the right to control their own bodies and access the reproductive health care they need, without obstruction," said New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman.

For more of our coverage on the New York clinic picketers trial, click here.

In the three years since the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous McCullen decision struck down the statewide reproductive clinic buffer zone in Massachusetts, clinic violence and picketing have been barely a footnote in the news cycle, even though they have been on the rise. Clinic protection remains off the radar for most public officials as well—making the news out of New York last week a big deal.

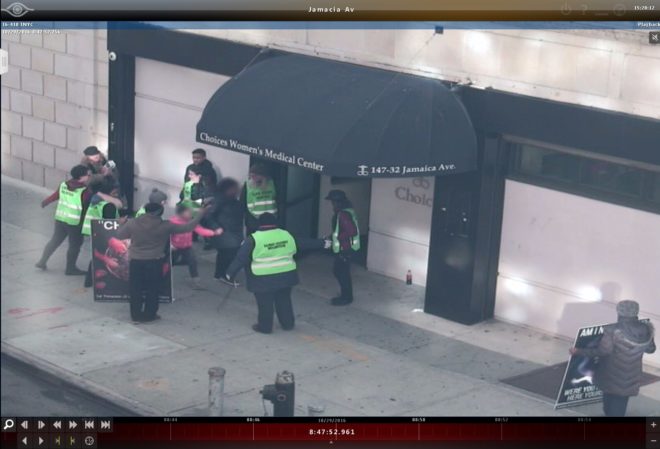

Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman announced on June 20 a federal lawsuit against a coalition of anti-choice protesters, along with “anyone acting in concert with them,” as well as an immediate preliminary injunction to end the persistent, dangerous harassment and threatening of patients, families, escorts, and clinic staff at the Choices Women’s Medical Center in Jamaica, Queens.

These tactics to “menace” clinic visitors are illegal, Schneiderman said in a statement. “The law guarantees women the right to control their own bodies and access the reproductive health care they need, without obstruction.” Schneiderman is referring to the federal Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act, the New York State Clinic Access Act, and the New York City Access to Reproductive Health Care Facilities Act, under which the lawsuit was brought. The FACE Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, is enforced by the Department of Justice.

In addition to the injunction and lawsuit, Schneiderman is seeking a 16-foot buffer zone (one foot larger than current law) around the clinic, which would protect neighboring businesses and community members as well. Because municipalities have been resistant to enacting new buffer zones—or, frankly, to enforcing already existing laws—since McCullen, this bold action by the New York attorney general is welcomed by reproductive rights advocates.

As a founding board member of the Clinic Vest Project (CVP), I’m connected to volunteer escort groups around the country, in Canada, and in the United Kingdom, and I personally volunteer for groups in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City (including Choices), and a clinic in Englewood, New Jersey, where I helped launch a new volunteer escort program in December 2013.

The attorney general’s statement summarizes behavior I witnessed on the occasions I was able to volunteer at Choices, when I lived in Brooklyn three years ago:

[E]very Saturday morning for at least five years, an aggressive group of anti-choice protestors, and those acting in concert with them, have tried to impede access to reproductive health care services by subjecting incoming patients to a barrage of unwanted physical contact, as well as verbal abuse, threats of harm, and lies about the clinic’s hours and its services.

I’m rooting for Schneiderman’s action not just as an advocate for reproductive health-care access, but also on a personal level.

I had the unplanned pleasure of meeting Schneiderman just over three years ago at a NARAL Pro-Choice America #MenForChoice event in NYC. We were waiting for the McCullen decision, so clinic harassment was part of NARAL President Ilyse Hogue’s donation ask that night. She gave me an unexpected shout-out from the stage as a witness to the targeting experienced even in a “safe, blue” state and city like New York. After listening to Schneiderman’s speech about his history as more than a “check the box” pro-choice advocate (he worked at a clinic that provided abortions when he was just 17 years old), I decided I’d grab the opportunity Ilyse had given me with the nod.

After the mic was nixed and people turned their attentions back to other attendees, I made a bee-line for the attorney general and (re)introduced myself. He was cordial, so I politely asked “Who do I talk to about a clinic in Queens where it takes 20 or more volunteers to protect patients every Saturday as NYPD stands and watches?” He immediately started patting his suit pockets looking for business cards and said, “Me. You talk to me.”

I connected with someone in his office the following week to set her up with two of the escorts I knew well, who had given me permission to pass on their contact information; she was out at the clinic bright and early—7:00 a.m.—the following Saturday to witness the harassment herself. She promised the attorney general’s office was taking this seriously and planned to investigate the groups and individuals targeting Choices. Because they are local rather than connected to well-known anti-choice groups with histories of mass, organized protests and paper trails, the investigation was going to be quite an undertaking.

Flash forward to last week, when a friend—also a former escort at Choices—sent me the statement announcing the lawsuit. I burst into appreciative tears. Naturally, I reached out to him for a formal response.

“I was excited, much like when the clinic in Englewood, New Jersey, had gotten a modest buffer zone ordinance passed in their city council,” Mike Nam told me. “Attorney General Schneiderman, who has a dogged reputation around these parts, is also someone I’m fairly confident would have his ducks in a row in order to win the suit. It would be a relief to know that even in ‘liberal’ New York City, patients seeking reproductive health services could get some respite from the anti-choicers that are even more emboldened after the recent presidential election.”

Karla Salguero, who volunteered as an escort at Choices for more than two years, was excited to hear the news as well.

“I was in shock,” she told me. “It’s been years in the making and I’m so proud of all those volunteers who helped make it happen. I am so overjoyed that this is finally getting the attention it deserves and am hopeful for change.”

Nam and Salguero backed up the extensive claims made in the lawsuit, having experienced the threats and harassment firsthand on their numerous Saturday morning volunteer shifts.

“Surrounding patients by edging them toward the wall until they really had nowhere was pretty awful,” said Nam. “The volume of some of the preachers—even after being told sound amplification was not allowed by cops—was horrendous at times, audible in the waiting room of the clinic.”

Both Nam and Salguero cited picketers aggressive behavior to patients arriving at the clinic by car, using their bodies to prevent passengers from exiting or sticking their hands into the vehicles to forcibly distribute their literature.

Salguero was particularly affected by the picketers’ use of children to harass volunteers and patients.

“I was upset by the fact that there were children, ranging from 6 to 12 I’m guessing, holding gory anti-abortion signs. I hated that they were often there in the middle of winter freezing,” she said. “One of the protesters would deliberately go up to children walking by and point to us and tell the children that we were killing babies.”

Children would be stationed with sizeable placards along the sidewalk from the corner to the clinic entrance, creating a narrow pathway that allowed picketers to better swarm patients even with a bubble of four or more escorts surrounding them for protection.

The protesters’ signs were impossible to miss—for patients and for others in the community.

“[T]heir ridiculous, inaccurate signs full of what look like mutilated babies,” as Nam described them, were a particular nuisance to local residents as well as the shops nearby.

“A lot of locals hate that part [the signs] of the experience particularly,” said Nam. “As I recall, a local corner business had to stop opening their regular hours on Saturday morning because the protests just killed any hope of business being done.”

Salguero described the different ways that individual picketers targeted specific patients and their companions—some shouting directly in the ears of volunteers or recruiting passersby to join in the harassment.

“At one point one of the protesters was visibly pregnant and she would stand in front of the clinic imploring patients not to ‘kill their babies’,” she said.” Male protesters would target men going into the clinic asking them to ‘step up and be a man.’ Asking them not to ‘let their women kill their baby.’”

Even as I celebrate the lawsuit, I know very well that laws and injunctions are only as effective as the will to enforce them. One of the things reproductive rights advocates have to drive home during trainings for new escorts, particularly those with enough privilege not to be wary of law enforcement, is that police will not always (or even usually) be on the side of the clinic, staff, and volunteers. Calling for police assistance is always a last resort, as the experiences of escorts at Choices bear out.

“Law enforcement would only make them curtail their most aggressive behavior and not because the police asked them to, but because they knew it would work to their advantage. Law enforcement couldn’t do much if the protesters pretended to be on their best behavior,” said Salguero. “Some of us thought having law enforcement there added another layer of anxiety; [we thought about how it would feel] if you’re a patient walking to your appointment and you see police activity and protesters in front of where you’re supposed to be going.”

“Being that it’s also a clinic in a lower-income neighborhood serving many patients of color, police presence was sometimes not something we were overly eager to seek if there were issues, for the comfort of those patients,” agreed Nam, who added that “many times the officers themselves didn’t seem to understand the harassment laws of New York.”

I see this issue around the country. When I volunteered weekly in Chicago, the response from law enforcement varied tremendously from neighborhood to neighborhood and even depended on who was on duty and responded to the call. Unless officers are trained in clinic harassment laws and patient rights, your average beat cop won’t necessarily know the applicable statutes or how their higher-ups want disputes to be handled. A captain at the clinic where I was stationed most often vowed to demand unit-wide retraining on the issue and promised to make sure marked cars drove by regularly on the usual picketing days. At one of our group’s other locations, however, police response was a coin toss at best, with officers regularly taking the side of the picketers.

I’ve heard stories in at least a dozen states where calling for police assistance is just as likely to result in escorts being told to disband in an effort to be “impartial” to the two sides.

Clinic harassment won’t end with one buffer zone or one lawsuit, but it does make an important public statement about our values as a culture, while absolutely protecting individual patients and staff from harm.