An Anti-Choice Group’s Extreme Tactics Backfire in Jackson, Mississippi

Abolish Human Abortion has made it its business to disrupt—and many would say terrorize—Fondren, the Jackson neighborhood that has been home to the state's last abortion clinic for nearly 20 years.

In February 2013, several other people and I were escorting patients to the Jackson Women’s Health Organization (JWHO), the last abortion clinic in Mississippi. Amid the protesters from Operation Rescue (OR) and Operation Save America (OSA) who were in their usual places holding big gory bloody fetus signs, shouting “Don’t kill your baby,” and reading scripture loudly, I saw a few people wearing “I’m an abolitionist” t-shirts. These picketers seemed a bit more aggressive: When they saw Black patients, they would yell, “Do you know abortion is Black genocide?”

I was gobsmacked. As a Black woman who can trace her family back to a plantation in Alabama, who that very day was standing on the ground that my Black ancestors died cultivating and helping to settle after it was stolen from our Native American sisters and brothers, the slogan on these newcomers’ t-shirts and their messages to patients were deeply, deeply offensive to me.

That was the first time I remember seeing members of Abolish Human Abortion (AHA), the group who has now made it its business to disrupt—and many would say terrorize—Fondren, the Jackson neighborhood that has been home to JWHO for nearly 20 years. Last month, it took its strategy to an even more intense level by launching what its members call the “Project Nineveh March.” But rather than convincing people who aren’t sure where they stand to come to the anti-choice side, their extreme tactics have pushed some locals toward supporting reproductive health clinics.

What Is AHA?

Before 2013, no JWHO volunteers or other local activists can recall seeing the AHA in Jackson. The small, mostly white and male, Oklahoma-based group is fairly new to the anti-choice scene. Still, reproductive justice activists and clinic defense workers already recognize them to be militant and extreme.

AHA members don’t consider themselves to be “pro-life”; instead, they call themselves abolitionists. According to the organization’s website, “When you call yourself ‘pro-life,’ you are letting people know what you think about abortion. When you call yourself an abolitionist, you are telling them what you aim to do about it.”

The only way to ensure “abolition,” according to the AHA, is to change the sinful culture they feel openly condones “child sacrifice in the form of abortion.” There is no middle ground; they are all or nothing. In addition to abortion, they believe in-vitro fertilization is murder. Hormonal birth control and emergency contraception are too. If anyone reads the AHA’s website or interacts with its supporters, it becomes clear their goal is to convert people to their version of Christianity, which will eventually change the culture at large to a place where it is unthinkable for anyone to attempt to access these services. In its members’ view, there is no way to be Christian and pro-choice, because abortion is evil and against God.

For the AHA, belief in religion is central to being part of its movement, and its supporters disdain “pro-lifers” who do not use religion as the central justification for their beliefs or work toward immediate abortion abolition as their only goal. Even so, AHA members attend OSA and OR events, and vice versa; while these anti-choice groups are deeply rooted in fundamentalist Christianity, they often focus on attacking abortion access through regulation rather than on eradication altogether. According to the AHA website, one can be a secular “pro-lifer,” but not a secular abolitionist, since, “To be an abolitionist you must believe in a higher law. One does not need to believe in a higher law or deity to embrace an adverse opinion regarding abortion.”

If the title abolitionist calls to mind images of the United States’ history of slavery, that is by design. AHA is known for its use of imagery and language borrowed from anti-slavery organizations and civil rights groups. Its members are not opposed to using slavery metaphors and imagery of enslaved Africans in their literature, videos, and protest language. One YouTube video posted by the AHA, for example, shows a white male member pointing to a white Jackson police officer and telling his Black colleague, “A couple hundred years ago, this guy would have owned you as a slave.” The AHA member went on to describe the way the Black officer would have been dehumanized if he had been enslaved by his white co-worker, claiming that the white officer would have enjoyed doing so.

AHA members see nothing racist, wrong, or problematic with these kinds of statements, which co-opt civil rights struggles for their own use. They have said as much in many of their online videos as well as their written posts; they have also stated such things when directly confronted by Black citizens of Jackson. Somehow, the fact that they exploit images of Black pain or that they are a group of mostly white men targeting and harassing Black women at clinics is lost on them. They think being in-your-face and offensive is needed to bring change and “shine a light,” as they say, on the “sin and evil” of abortion, IVF, and hormonal birth control.

Most of all, though, they seem concerned that the residents of Jackson are not distressed enough that these things exist in the area. The AHA named Jackson “The City of Blood” this year in its literature and several videos, even though Mississippi has one of the lowest abortion rates in the nation and little access to birth control. It also has one of the highest rates of church attendance in the country. Still, any reproductive rights at all are apparently too much for the AHA.

Why the Fever for Fondren?

Except for its supporters’ appearances at clinic protests and one attack targeting me and my children on Twitter, the AHA was pretty much invisible in the Jackson area during 2013 and early 2014. In late 2014, though, there were rumblings online and throughout the activist community that AHA was starting a specific chapter in the Jackson area. This would mean rather than just parachuting in and causing chaos, they would be building a base of people to keep up a persistent presence like they have done elsewhere.

Now, to understand why AHA—and every anti-choice group in the country—wants to be in Jackson, you need only reflect on the last three years of legislative and legal activity around abortion rights. JWHO, or the “Pink House,” is the only clinic in Mississippi, and its ability to stay open hinges on the latest court ruling from the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The clinic has been to court several times, but every time, anti-choicers hope this will be the time they can dance on the grave of the Pink House and say they helped make Mississippi “abortion-free.” As the case bounces through the courts, more anti-choice activity has been arising—including the establishment of the Jackson AHA chapter.

The residents and businesses of Fondren have long ago become somewhat accustomed to the people who occupy the sidewalks outside the clinic. And if there is one thing I’ve learned in my time as an escort, the president of Mississippi National Organization for Women, and the co-founder of an abortion fund, it’s that even in Mississippi, the buckle of the Bible Belt, clinic protesters get very little love from the community. Business owners who are “pro-life” and do not actually support the clinic, per se, will all come together in agreement that the harassment outside the clinic isn’t “sidewalk counseling” or good for anyone. It creates a hostile and abusive environment around the clinic that, by design, spills over onto other businesses. Fondren is also full of vocal supporters of the Pink House.

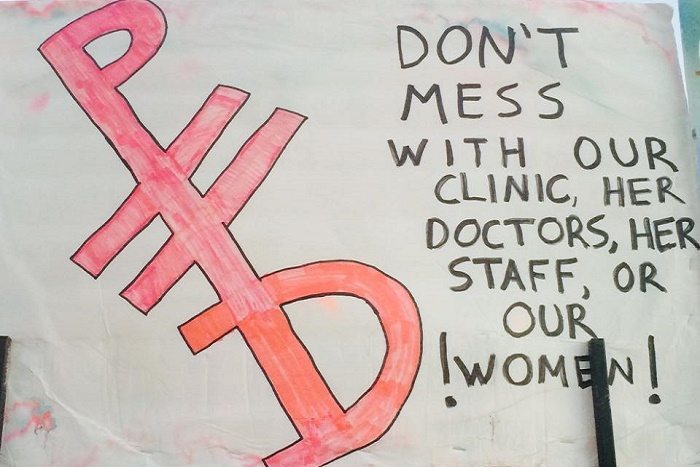

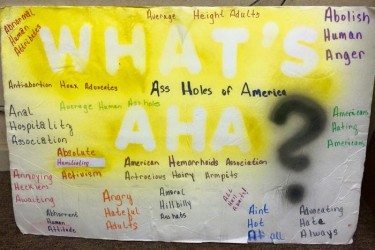

When this new chapter of AHA arrived at JWHO toward the end of 2014, the well-trained Pink House Defenders who volunteer to do clinic defense and escorting were ready for their arrival. They had made a few signs specific to AHA. One had a host of things AHA could stand for, like “angry hateful adults,” “annoying hecklers awaiting,” “anti abortion hoax advocates,” and “Americans Hating Americans.” Another sign took the AHA logo and turned it into a logo that says PHD, for Pink House Defenders. AHA members expressed their discontent with these signs verbally at JWHO, then later railed against them on social media.

But unlike OR, OSA, and other local anti-choice efforts, the Jackson AHA—with some out-of-town help—has decided to go several steps further than yelling at patients in front of the Pink House. On Easter Weekend 2015, the national AHA began a series of campaigns it called Project Nineveh, in which its members “go out into the cities, highways, and byways calling all to repent of their apathy and participation in child sacrifice.” In Jackson, that means going to local schools, protesting churches near the clinic on Palm and Easter Sunday, and interrupting the Zippity Doo Dah parade held by the Sweet Potato Queens annually to raise money for Mississippi’s only children’s hospital.

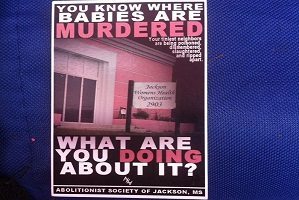

AHA has also made handouts specifically targeting the Fondren neighborhood, in which it used a local landmark’s logo and called the clinic—as well as surrounding businesses and churches—“bad neighbors” to embryos. All of Fondren is “evil” and “full of blood,” according to one AHA video, because the community stays silent rather than “rises up” against the “child murder” occurring in its midst—not that the AHA ever defines what “rising up” would entail. These are different from the one-size-fits-all-cities fliers the AHA normally uses. Its supporters are leaving these slickly produced pamphlets, which are full of bloody fetus imagery, all over the Jackson metro area, placing them on shelves (often next to Plan B) and even alongside items at local businesses.

Stephen Wilson and his partner found this out firsthand when they visited Bass Pro Shop in Pearl, Mississippi. Wilson told me, “When I found the literature, I was appalled that those images were within reach of children.” Wilson continued, “I photographed the literature, and placed it in the trash where it belonged. I’m strongly pro-choice and it struck one of my liberal chords.”

Wilson isn’t the only resident who is disgusted and fed up. Since the incidents beginning on Easter weekend, the ongoing campaigning has many residents commenting on public forums regarding their dislike for AHA tactics, which have also included leaving their drop cards at pharmacies on shelves next to Plan B and aggressively talking to and taping local children without parental permission. On the AHA Facebook page, locals have expressed both their support for the clinic and their disgust at the tactics of the group.

Fondren resident Scott Crawford commented, for example, “I’m proud to live just down the street from Jackson’s Woman’s Health Organization, and I stand with women and their right to choose. Those circulating hateful literature are the bad neighbors.” Some neighborhood residents have been talking about ways to combat the group’s aggressive strategies. No one has come up with a clearly defined way to let AHA know it is unwanted yet, but many people in the area have simply committed to collecting and throwing away AHA literature whenever they see it.

Michelle Colon of the Pink House Defenders thinks that AHA likely made the Fondren-specific fliers after exchanges with her and other members of the PHD, in which Colon said JWHO was “the heart of Fondren.” JWHO has been unapologetic about providing abortion services and being a part of the neighborhood, a message AHA clearly wants to turn into a negative.

However, the AHA members are betraying their ignorance of the community they’re invading. “They don’t even know Jackson,” Colon pointed out. “They thought the Zippity Do Dah parade was a Pride parade,” she said. The Sweet Potato Queens, who have hosted the parade in Jackson for over a decade, are mostly made up of cisgender, middle-class, straight white women. AHA described the parade on a YouTube video as being full of “pole dancers and drag queens.”

From the ground, it seems as if AHA is making few friends and many enemies with its blatant racism and extremism. A coalition of activists, residents, and business and community leaders is beginning to call for action to combat the group’s manipulation of the law in order to push its message. But overall, the best weapon against the AHA is showing its members they aren’t welcome and no one wants to listen to them. People aren’t receptive to being harassed on the street as they conduct their day-to-day affairs—and when they make the connection that this is what women experience as they enter clinics, they tend toward empathy for patients rather than support for the AHA.

AHA’s presence is helping to create the kind of dialogue among people who usually wouldn’t work together necessary to fight the harassment of anti-choice extremists. For me, that doesn’t make dealing with them in our city worth it. But it is a good thing for the abortion rights, pro-choice, and reproductive justice movements.

In the South, it is rare that people who are on the fence or even timidly support abortion rights would come out and vocally oppose anti-choice groups. Mostly people turn their eyes away, or see them as a benevolent educational, religious, and caring force. But AHA’s tactics are revealing the ugly, extreme face of the movement, and their true views regarding birth control and IVF too. Jackson’s lone pink clinic has been enduring this abuse for years. Now that the harassment is consistently spilling out into the community, people are finding that they have to make a choice. They can buy into the terroristic narrative that the harassment is the clinic’s own fault, or recognize that this kind of behavior is not OK and must be stood up to.

It appears that many people in Jackson—and Fondren specifically—are realizing that bullies must not be tolerated, even if you don’t fully like or support the target of the bullying. And this should be a wake-up call for AHA supporters as they attempt to spread their hateful messages across the country: If they can’t find a receptive audience in the buckle of the Bible Belt, they are unlikely to find one anywhere.