Case Records of Children ‘Disappeared’ Into Adoption Destroyed in El Salvador Attack

Recently, the investigation files on children forcefully disappeared during the 13-year civil war in El Salvador were destroyed in an attack on the offices of Asociación Pro-Búsqueda—seemingly part of an orchestrated campaign to destroy evidence related to the genocidal acts committed during the civil war.

Recently, the investigation files on children forcefully disappeared during the 13-year civil war in El Salvador were destroyed in an attack on the offices of Asociación Pro-Búsqueda (Pro-Search Association) in San Salvador. This attack seems to be the continuation of an orchestrated campaign to destroy evidence related to the genocidal acts committed during the civil war. This particular act of destruction is part of a long history of child abduction in Latin American and the prevalence of what has been called a culture of impunity preventing due justice for the cases of children disappeared during civil wars in various Latin American countries.

The forced separation of children from their parents who were identified and persecuted as insurgents during civil war has a repetitive history in Latin America. The atrocities in Argentina’s “Dirty War” (1976-1984) are notorious, and in July of 2012 Argentinean General Jorge Rafael Videla was sentenced to 50 years in prison for his role in crimes against humanity during that war. Among those crimes that featured prominently in his recent trail were illegal child adoptions—infants entered into illegal adoptions after their mothers were systematically executed. Many applauded this conviction as an important step in accountability, and trials like Videla’s help in confronting the past atrocities of a war in which at least 30,000 Argentineans died. Prosecuting such a high-ranking military official for war crimes is remarkable in a region known for amnesty and impunity.

Guatemala’s civil war (1966-1996) resulted in at least 200,000 deaths and countless other individuals disappeared as a result of genocide. Testimony indicates that an unknown number of children entered into illegal adoptions internally, while others were sent overseas as adoptees. That country’s recent attempts to hold former dictator General Rios Montt accountable have been unsuccessful thus far, but he too is implicated in many war crimes. While Montt’s case is very complicated and we don’t want to over-simplify here, evidence in recent court hearings included a full day of testimony from rape victims. Montt is also believed to have been involved in illegal adoptions.

Sadly, neighboring El Salvador shares a similar history of civil war (1979-1992). This particular conflict resulted in the deaths of at least 75,000 people, while a half million others were internally displaced and nearly one million Salvadorans sought refuge in other countries. Amidst death and displacement was the loss of family life—some children were forcibly removed from families as an act of reprisal. Other children were spared death as their adult family members were executed, while some children were simply lost from their families during the chaos. An unknown number of children entered into adoption; some children were adopted by military and other elite families in El Salvador while other children were sent into overseas adoptions in the United States, Europe, Canada, and elsewhere. Some of these international adoptions cost as much as $10,000, underscoring the human trafficking element of such illicit adoptions.

Today, a movement to reunite the lost children of Salvador’s civil war has resulted in the momentum of Pro-Búsqueda. A powerful force in truth and reconciliation, Pro-Búsqueda has reunited hundreds of now adult children with their lost family members in El Salvador. The organization provides support services to those in the search and reunion process, including the counseling necessary when individuals learn the truth about their loss of family life during civil conflict.

To aid in reuniting Salvadoran families, expert organizations, such as the Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley have developed a DNA database so that the lost individuals and families may be matched using modern technology. Each success story is not only profoundly emotional, but in the telling of the social history the dark past of El Salvador’s disappearances continue to come to light some 20 years after the war ended.

Pro-Búsqueda serves as a powerful advocacy organization, bringing the difficult subject of disappearance during civil war into contemporary discourse. Among the accomplishments is the organizational history of bringing cases before various courts, including the Inter-American Human Rights Court (IACHR). Also, since October 2007, Pro-Búsqueda has filed habeas corpus (constitutional right of protection of rights and liberty) recourses in over a dozen cases in national courts. Their voice is loud and effective.

Pro-Búsqueda’s work in the policy arena resulted in major steps forward when, during the 137 Period of Sessions of the IACHR, the Salvadoran government committed to establishing a special commission to search for the disappeared children, including the creation of the publicly funded DNA bank. In January 2010, on occasion of the Peace Accords anniversary, in addition to asking for forgiveness for human right violations, the government announced a new commission to investigate the disappeared children.

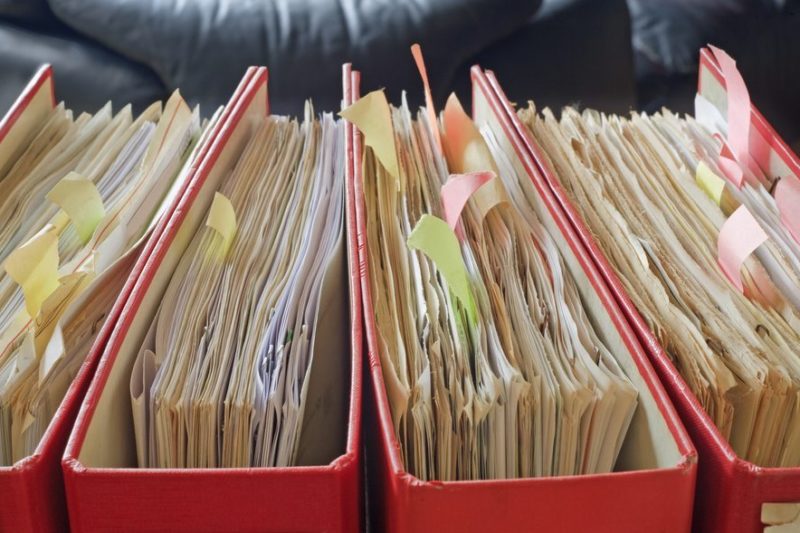

In memory of those who disappeared during the civil war, the organization is in the practice of keeping meticulous records of their investigations, including testimony of survivors looking for lost loved ones. In fact, documentation is one area of Pro-Búsqueda’s expertise, and their search and reunion process depends on first-person accounts of the crimes that led to family-child separation.

In the early morning hours of November 14, Pro-Búsqueda’s offices were ransacked by armed men who set a fire to paper records. The organization’s computers were also stolen. The destruction of records from past and present cases is not only stunning, but the attack leads to the obvious question: Who was so threatened by the case files of Salvadoran families attempting to search for the whereabouts of their missing children?

In a tweet from Pro-Búsqueda Director Ester Alvarenga, it was clear that the organization considers the events to be a terrorist act. Notably, the incident comes after the September closing of Tutela Legal, the main office collecting this type of evidence for the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation established in the post-war phase of documentation. The Constitutional Court recently agreed to consider the petition for cancellation of an important amnesty law.

The act of document destruction can also be characterized as further victimization of the families whose children were forcibly disappeared and “adopted.” Alvarenga expressed her indignation because, in addition to destroying the case files, the perpetrators also destroyed the pictures of Jon Cortina, one of few survivor Jesuit priests who helped the searching families establish the association. This act seems to aim at shooting down the “voices of the voiceless”—the children and families torn apart due to child abduction into adoption.

Other human rights defenders also link the destruction of records to a decision made by the Supreme Court to accept a case that will challenge the constitutionality of El Salvador’s 1993 Amnesty Law. The Committee in Solidarity With the People of El Salvador (CISPES) reports that this law has “protected top former government and military officials from prosecution for war crimes and grave human rights violations.” CISPES also raised concern about the protection of other war crime records, which has been called into question as the major archive previously in oversight of Tutela Legal, and now in possession of the Catholic Church Archdiocese.