What’s Up With Women and HIV-Prevention Method PrEP?

PrEP works when used properly. So why don't women use it?

At the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Atlanta this week, researchers reported that, in a large scale trial among African women, neither oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) nor the daily use of vaginal gel containing an anti-retroviral (ARV) drug had shown effectiveness in reducing HIV risk.

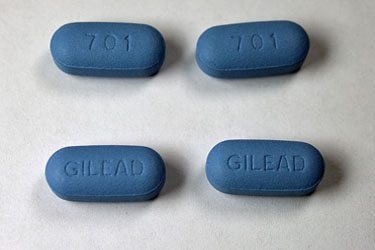

The clinical trial, Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic (VOICE), enrolled 5,029 HIV-negative women and randomized them into five study arms. In one group, women were asked to take an oral tenofovir (an ARV tablet) daily. In a second arm, women tested the daily use of oral TDF/FTC (a two-ARV combination called Truvada), and in the third, women were asked to insert a vaginal gel containing 1 percent tenofovir gel that had been shown in a previous study to provide moderate protection against HIV.

The fourth and fifth arms were placebo controlled; women received either a pill or a gel that looked identical to the study products but contained no active ingredients. Comparing the rate of new HIV infections occurring among women in the control arms with those of women in the various intervention arms allowed the researchers to see if the use of the interventions reduced women’s rate of HIV acquisition. Participants in all arms were also regularly provided with free condoms, counseling about the need to use condoms consistently, and testing and treatment for sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) to reduce their HIV risk to the greatest extent possible.

Despite the fact that other trials of oral PrEP have shown some effectiveness in women, none of the VOICE interventions resulted in decreased HIV acquisition rates. Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, co-principle investigator for the VOICE study, reported in her presentation at CROI that it appears relatively few participants in intervention arms of the trial actually used the products daily as instructed. By testing blood samples for the presence of the ARVs in the body, the researchers saw that only 25 to 30 percent of the women were using the products as instructed. A similar lack of adherence to daily product use also led to discontinuation of the FEM-PrEP trial in 2011.

The VOICE results are particularly frustrating and sad because of the high rates of new HIV infection that occurred among women in the trial. Even with the benefits of medical care, free condoms, condom counseling, and more, the rates were high—6.3 percent among women in the oral tenofovir arm, 4.2 percent in the placebo oral arm, 4.7 percent in the Truvada arm, 5.9 percent in the tenofovir gel arm, and 6.8 percent in the placebo gel arm. The researchers reported that the greatest number of new infections occurred among women who were under the age of 25 and unmarried. The rate of women becoming HIV positive was less (although still high) among women who were over the age of 25, married, and/or who had partners over the age of 28. This pattern is prevalent globally. Even in the United States, younger women are at greater risk of HIV than their older cohorts.

This is also frustrating because we know that PrEP works when people use it. Data demonstrating this led to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of Truvada for HIV prevention in the United States last year. In a 2010 study called iPrEx, Truvada reduced HIV risk among men and transgender women who have sex with men by 44 percent. Data from this study suggested that participants who took the drug strictly according to schedule and did not miss doses were up to 73 percent less likely to become infected. Adherence is a challenge across the board, however. About 50 percent of iPrEx participants were estimated to be adherent to the study protocol.

Other studies enrolling both women and men have also produced encouraging effectiveness data. In Partners PrEP, a study enrolling couples in which one partners was HIV-positive and the other was HIV-negative, effectiveness was shown to be 75 percent and adherence was estimated at 80 percent. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) TDF trial also showed adherence of about 80 percent, and the HIV risk of participants using the product was lowered by 63 percent.

So why is it that the two studies conducted exclusively among women did not yield evidence of effectiveness, when other studies enrolling both women and men did? What are the barriers to adherence that result in women finding themselves unwilling or unable to use this intervention daily? No answers to these questions are immediately apparent, although both the VOICE and the FEM-PrEP data are being further analyzed to look for clues.

If PrEP works for women (and men) when they use it, then why don’t women use it? Finding these answers will likely require additional research into the structural and cultural factors that shape behavior, perceptions of risk, and decision-making about sexual and health issues.

The U.S. Women and PrEP Working Group, a coalition of more than 50 women from leading AIDS and women’s health organizations, released a position statement this week highlighting factors likely to shape PrEP use (or lack of use) among women domestically. Working group Chair Dazon Dixon Diallo, the founder and president of SisterLove, Inc., observed that “[w]hile the clinical science is clear, the social and behavioral implications are less so, and we now need to develop and fund demonstration projects that will help answer a range of questions about real-world use of PrEP by American women and move toward an integrated plan for PrEP rollout in our communities that includes support for healthcare providers, social workers and others who will help women use PrEP effectively.”

Manju Chatani-Gada, senior program manager at AVAC and co-convener of the working group, added that “we have much work to do to understand what social, cultural and other factors affect adherence to the prescribed dose and how we can support women in effectively using new prevention tools. But PrEP remains a valuable option for many women who will want to and can use it as prescribed. Well-designed demonstration projects will help us understand adherence and other real-world issues for women who choose to use PrEP.”

The working group is calling for a coordinated, timely, and adequately funded domestic response to PrEP for women—a response that involves the full participation and leadership of individuals and communities most in need of effective, comprehensive HIV prevention. Its statement calls on the White House’s Office of National AIDS Policy and the CDC to work with the group to develop a national coordination plan for how Truvada will be rolled out to U.S. women.

Given that no clinical trials on PrEP have enrolled American women, the Working Group points out that there is a complete lack of evidence regarding how daily PrEP can best be promoted, made accessible, and financed in ways that ensure its uptake among U.S. women who want to use it and can benefit from it. Prompt action is required to fill the gaps in PrEP research, public and provider education, social marketing, and public policy. All of these are needed to support the next steps in developing a comprehensive roll-out plan for PrEP among women at high risk of HIV in the United States.

Preliminary social science research done on U.S. women and PrEP shows that most women surveyed had never heard of PrEP. After being informed, however, they expressed interest in using it if it were shown to be effective and promoted by people they know and trust. These data were gathered from 92 women in four U.S. cities. Key concerns that women expressed included cost, effectiveness, and side effects, including concern about possible interactions with hormonal contraception.

The working group’s statement raised a number of additional concerns that women have expressed anecdotally with regard to PrEP use, including:

- Will some sex workers be pressured by their employers or managers to use PrEP because male clients dislike condoms?

- Will some women be pressured by their partners to use PrEP instead of condoms?

- Are there possible interactions between Truvada and the female hormones many transgender women use?

- Will there be drug interactions between PrEP and recreational drugs?

- Are there long-term health effects from Truvada for children whose mothers use PrEP during pregnancy or breastfeeding? How can these be tracked beyond the first year of life covered by current PrEP registries?

These real-life concerns directly affect interest in PrEP among women at high risk of HIV. Failure to find answers, and to educate care providers so they can discuss PrEP knowledgeably with women patients, will discourage women from using this effective HIV prevention tool. Ignoring these gaps brings us to a future point of wondering domestically, “If it works when women use it, why don’t women use it?”

Women living with HIV in the United States have higher death rates than their male counterparts, higher rates of hospitalization, and experience more than twice as many HIV-related and AIDS-defining illnesses per person than their male counterparts. In 2008, nearly two-thirds of them had annual incomes below $10,000, compared to 41 percent of men living with HIV. Nearly three-quarters of women living with HIV had a high school education or less.

Most women living with HIV in the United States are already heavily disadvantaged. It is important that we not let lack of access to PrEP—because women aren’t hearing about it from their peers and community-based organizations, they can’t get their questions about it answered, they can’t afford it, or their health-care providers aren’t offering it to them—be added to the long list of disadvantages they currently encounter. We cannot let PrEP become a prevention tool regularly accessed by affluent men at risk of HIV, but not women.

“Male and female condoms are wonderful HIV-prevention options that work for many women and their partners. But some women can’t insist their partners use condoms, and many young women and their HIV-positive partners want to have children,” said Erika Aaron, a nurse practitioner at the Drexel University School of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine. “Those women need other options to protect themselves from HIV. PrEP can help them stay HIV-negative. We have a moral imperative to find ways to make it available to women who need it and who can use it.”