Opposing Religious Coercion in Health Care: The Defeat of the Abington Hospital Merger in Pennsylvania

In Pennsylvania, organizing by community members and medical professionals helped defeat a merger between a Catholic hospital and a secular hospital system, thereby ensuring that women's reproductive health care services are still offered.

When Rita Poley created the “Stop the Abington Hospital Merger” Facebook page, she had no idea what would happen next.

For the 69-year-old Elkins Park, Pa. resident, it was a way to connect with other Montgomery County community members outraged by the abruptly announced partnership between the secular Abington Health (AH) and the Catholic-affiliated Holy Redeemer (HR), both located in the metro Philadelphia area. The Facebook page, created July 3—a week after the merger was revealed—was a means to initiate debate about “the horrible situation that was now present in our community.”

That horrible situation? The creation of a new regional health system formed between Holy Redeemer and Abington Health (which encompasses its flagship hospital, Abington Memorial Health (AMH) and Lansdale Hospital in Hatfield Township, as well as two area outpatient facilities), would mean total elimination from the hospital system of abortion care, even as Abington Health still claimed to remain a secular institution. Abington Health doctors and community members claim they were not consulted about this decision—or the partnership—before it was announced.

“This is just very, very, very close to my heart, this issue,” says Poley of her passion to fight against the partnership and its implications for women’s reproductive health care. Poley, director and curator of Elkins Park’s Temple Judea Museum of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel for the last 13 years, came of age during the fifties when “these battles were being fought. I had friends from college who had to endure back alley abortions.”

But what began as a suggestion from her 44-year-old daughter Nomi Saunders turned into the straw that broke the camel’s back.

And all in a matter of over two weeks.

“In the 15 years we’ve been doing this, this is the fastest merger defeat we’ve ever seen,” says Sheila Reynerston, advocacy coordinator for the New York-based MergerWatch Project. “It was 20 days. That’s incredible.”

A Swift Change

On July 18, after an emergency hospital board meeting, both Abington Health and Holy Redeemer released a joint statement announcing that the merger was dead.

Together we had a bold vision that we believe would have served our community well. While we are disappointed, we believe this decision is in the best interest of both organizations.

Why the merger fell apart in the end is at this point only a matter of speculation, but Poley and others involved in the campaign against the partnership believe it had a lot—if not all—to do with the grassroots efforts in the Montgomery County community. After all, the Facebook page had 1,470 likes as of July 20, 10,000 community members were sporting “Stop the Abington Hospital Merger” pins, and a Change.org petition against the merger received more than 6,100 signatures. (Linda Millevoi, spokesperson for Abington Memorial Hospital responded to an Rewire inquiry about the end of the merger delining further comment, and did not respond to requests for further clarification as of press time).

“I had no idea what was going to happen but I knew if anything was going to happen, we had to have a way to come together,” says Poley. “Facebook really is the 21st century town square.”

Poley, who heard the news while conducting a tour at the museum, also cites her talk with Abington Memorial Hospital’s Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Meg McGoldrick, on July 13. According to Poley, when McGoldrick called her to inquire about a sit-down meeting to discuss an accommodation, in which AMH would establish an off-site facility for abortion services, Poley refused. Instead, she informed McGoldrick that everyone involved in the campaign was developing strategies that would help end the merger. “I told her…it was going to get much worse, and I think she heard me,” she asserts.

“The movement created by the community against this merger was unprecedented,” says Reynerston, who attended a meeting with campaigners, along with representatives from Catholics for Choice and American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) the night of July 17. “There was so much good use of social media and in such a short amount of time. It was quite clear that the community was very unhappy.”

“It was an impressive show of dissent against an ill-planned proposal,” she adds.

Another factor that can be attributed to the suspension was the overwhelming number of letters of discontent—most of which Poley posted to the Facebook page—that swamped the inboxes of the Abington Health administration. One such letter, sent July 3 by eight local Rabbis to Abington Health President and Chief Executive Officer Laurence M. Merlis wrote of the merger:

While we respect Catholic teachings that regard a fetus as a potential life, and understand that a Catholic hospital would refuse to provide abortion services, we are deeply concerned that this decision imposes a Catholic religious worldview on the entire community…In making the decision to no longer provide abortions at AMH, you are in effect saying that one religious tradition’s teachings should take precedence over all others. Should AMH commit to this path and refuse to perform abortion services, it would seriously undermine its status as a community hospital in any meaningful sense of the term.

“As a Rabbi, I don’t look at this as a political issue, I look at this as a moral issue,” says Rabbi Lawrence R. Sernovitz of Old York Road Temple-Beth Am in Abington, one of the letter’s signers. “The moral issue is [that] women should have the right to have the services that they need in their own community… To take away the rights of women for a financial decision is not appropriate if you are serving the greater community.”

The Doctors Didn’t Buy It

But it wasn’t just the local clergy or citizens that were dismayed by this secular-religious partnership and subsequent elimination of abortion services. Over 200 AMH-affiliated doctors, including residents of AMH’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, met July 11 and unanimously opposed the planned merger, says Dr. Sherry Blumenthal, a 22-year Abington Health OB/GYN physician, Womencare Obstetrics and Gynecology P.C. partner, and chair of the Pennsylvania section of American Congress of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG).

Dr. Blumenthal was on vacation during the meeting but attended by phone (she notes in a July 19 follow up email that she was away during most of the campaigning but was still actively involved). She also authored a letter dated June 29 speaking out against the merger, and was one of the most outspoken of the Abington Health physicians. In her letter to Merlis, she wrote:

It is apparent that this was not a medical decision, but a financial one. Abington Memorial Hospital, by agreeing to certain religious concessions in its merger with Holy Redeemer Hospital, is showing disrespect for the medical rights of women, their autonomy to choose when to have children, and how many children to have.

“The concept of the merger itself is not a problem for the physicians or the community in the sense that most [doctors] understand that health care systems are greatly challenged in terms of finances, and this will become worse in the future,” she says. “The problem with this merger is the compromising the secular nature of Abington Hospital with the Catholic theology.”

According to July 24 post on the Stop the Abington Hospital Merger Facebook page, a letter from Abington Health has been emailed to a number of merger distracters further explaining the choice to call off the partnership. The letter, which was attributed to both Merlis and AMH Board of Trustees Chair Robert M. Infarinato, states:

While the affiliation made sense from many perspectives, we were unable to resolve a number of difficult issues, including clinical differences related to reproductive health…

We are grateful for the long-standing support of our community, and we respect and value the views and opinions of those who care deeply about our organization, including members of our medical staff, our patients, our employees, our volunteers, our donors and so many other members of our community.

As noted above, however, community members say they had no knowledge of the partnership before its announcement, directly contradicting the claim by Abington Health that the company “respects” the opinions of those its employs and serves. Second, Dr. Blumenthal notes that AMH’s OB/GYN department, as well as most of Abington Health’s 1,400-plus doctors, were left out of consultations about the medical impact of the potential merger. According to the physician, Dr. Joel Polin, chair of the OB/GYN department, was the only one informed of the decision originally, yet was denied the opportunity to voice his concerns at a board meeting scheduled to vote on the matter. Abington Memorial spokeswoman Millevoi, however, believes that there is a “misperception” on whether the announcement on the proposed merger indicated it was a “done deal.”

“What the boards agreed to was the signing of the letter of intent, which was in fact, never actually signed,” she wrote in an email.

“On the day of the announcement, our chief of staff, Dr. John J. Kelly, called and met with a variety of constituents, including physicians. Contact with these various constituents were unable to be made until after the official announcement due to confidentiality requirements.”

Dr. Blumenthal has a different take of the overall situation. “I believe the talks were done in secret because the administration did not think that stopping abortion would be as big an issue or so controversial and they may also not have wanted to know this. They grossly miscalculated,” she wrote in the follow up email before the June 24 letter was distributed. She was on the beach with her four-year-old grandson when she heard of the cancellation, and felt “relief and affirmation.”

“Without medical input, the extent of the issue and the fears of where one prohibition might lead were trumped by financial concerns and fear of future financial constraints—the latter are real concerns. They might not have proceeded if they asked the medical staff and community first, so it is a bit of a ‘Catch-22.’”

Religion Over Health Care

According to a February 28 New York Times editorial, “Women’s Health Care at Risk,” 20 mergers between secular and Catholic-affiliated hospitals were announced over the span of three years, with more to be expected. It’s an upsurge, claims the editorial that is “threatening to deprive women in many areas of the country of ready access to important reproductive services.” In fact, notes the piece, late last year, Kentucky Governor Steve Beshear rejected a merger between secular and Catholic hospitals—University Hospital, Jewish Hospital, St. Mary’s Healthcare, and St. Joseph’s in Lexington—citing concerns about “loss of control of a public asset and restrictions on reproductive services.”

And this was the case of Abington Health and Holy Redeemer. In addition to the elimination of abortion services, AMH physicians and the Montgomery County community feared that other reproductive health services banned under the United States Conference of Bishops’ Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services would have been affected down the line.

“Abortion is one issue, obviously the issue that matters most to the OB/GYN department, but there are other reproductive issues that are extremely important as well,” says Dr. Blumenthal. “The concern about women’s health care is obviously huge and complex.”

According to a July 12 statement emailed by Millevoi, only 48 out of the 17,575 abortions performed in the five-county Philadelphia region were provided by Abington Memorial Hospital in the 12 months ending in March. But the types of abortions performed by AMH are often not viable in an outpatient setting. Instead, notes Dr. Blumenthal, most pregnancy terminations were high risk or second trimester abortions either to save a woman’s life or due to fetal chromosomal or other fetal anomalies. And these types of procedures, she says, are safer performed in a hospital setting.

In the same statement, Abington Health claims that it would have still provided “the full range of reproductive health options…including:

- Contraception counseling and services

- Tubal ligations

- Vasectomies

- Infertility services

- Emergency contraception for rape victims and others

- All necessary measures to preserve the health of the mother, including those that may result in terminating a pregnancy”

But just because it’s in writing doesn’t make it true, especially since all of these services are forbidden in the Catholic directives—and that’s exactly what doctors and residents were afraid of.

Reynerston points to a case last year in Sierra Vista, Arizona to illustrate this very real possibility. According to the MergerWatch advocacy coordinator, in April 2010, the independent secular Sierra Vista Regional Health Center (SVRHC) announced that it would partner Carondelet Health Network, a Catholic health system, in a two-year trial affiliation. As part of the alliance, which required SVRHC to follow the Catholic directives, tubal ligations at the time of cesareans would no longer be performed—and SVRHC went as far as to put a full-page ad out to the community stating what services were still available, one being miscarriage management, says Reynerston. Yet, three months after the announcement, a woman who was rushed to the emergency room for miscarrying the second of her twins (she miscarried one of her two 15-week twins at home prior to the visit), was forced to be transferred to an acute care facility 80 miles away. The reason? The attending physician who determined that pregnancy termination was necessary because the remaining twin could not survive checked with administration knowing that SVRHC was now under Catholic rule, and was told treatment was not possible at the hospital.

The case, states Reynerston, was used in a complaint filed with the Arizona Attorney General delivered in November 2010 against the affiliation. In April 2011, Sierra Vista Regional Health Center discontinued the partnership (in a July 9th article in The Sierra Vista Herald, SVHRC announced they were looking to partner again to build a new multi-million dollar facility but will not consider religiously-affiliated entities).

MergerWatch Director Lois Uttley believes the problem with the type of proposed partnership between Abington Health and Holy Redeemer is that the interpretation of the Catholic directives is up to the local bishop or archbishop. In the case of Philadelphia, Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of the city’s Roman Catholic Archdiocese, formerly Denver’s prelate, is “quite conservative,” says Uttley. (According to a July 2011 interview with the National Catholic Reporter, Archbishop Chaput alluded that it was “hypocritical” for pro-choice Catholic politicians to receive communion and that “a relationship between two people of the same sex is not in line with the teachings of the church and the teachings of the Gospel, and is therefore wrong.”) She adds that MergerWatch worried he would insist the reading of the abortion ban would be “broader than Abington Hospital officials might want it to be.”

And this means that, in addition to the services Abington Health claimed would still be provided, other services such as treatment of ectopic pregnancies and miscarriages could have eventually been restricted due to Archbishop Chaput’s interpretation.

The Financial Side

In the New York Times editorial, health care system partnerships are often driven by “shifts in health care economics,” in which “some secular hospitals are struggling to survive and eager to be rescued by financially stronger institutions, which in many cases may be Catholic-affiliated.”

But for Abington Health, this is not the case. Unlike Holy Redeemer, Abington Memorial Hospital received a Fitch Rating of “A,” with an outlook of “stable.” Among the key rating drivers, which included good market position (AMH “maintains a leading market share in a competitive service area,” states Fitch), solid liquidity, and above average debt burden, there sis sustained probability. Writes Fitch:

After a drop in profitability in fiscal 2010, Abington’s operating performance improved in fiscal 2011 with a 2.1 percent operating margin mainly due to its cost reduction initiatives. This trend has been sustained through the 11 [months] ended May 31, 2012 (interim period) with a 1.9 percent operating margin.

According to Moody’s, however, Holy Redeemer has $86 million of outstanding rated debt as of December 2011, receiving a Baa2 rating and an outlook of “negative”—the same rating and outlook it received from Moody’s in December 2010, when it had $110.9 million of total rated debt. One of Holy Redeemer’s challenges, writes Moody’s, is “ongoing pressure on operating cash flow.” The Catholic health system had an 8.1 percent operating cash flow margin the 2011 fiscal year, “with challenged operating performance during the first three months” in the 2012 fiscal year. There was also a $588,000 operating deficit during the three months ending in September 2011.

“It doesn’t make sense that Abington Hospital, being the financially stronger partner, would agree to any restrictions on its services in order to partner with Holy Redeemer,” says Uttley of the failed partnership. “Each hospital should be able to maintain its own ethical policies and current service provisions.”

As Dr. Blumenthal notes, Abington Health partnering with another hospital in the geographical area would position the system to become a stronger health care force. But she also finds it suspicious—and perplexing. “The structure of the board of the merged institution would be 50/50 [and] this makes no sense,” she says. “Why is Holy Redeemer being allowed to dictate certain conditions of the merger based on Catholic religious principles?”

Abington Health did not return a request for clarification on this issue.

And Then There Were the Residents

The other issue the unsuccessful merger presented was its effect on residency training in Abington Memorial Hospital’s OB/GYN department. According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Obstetrics and Gynecology program requirements:

No program or resident with a religious or moral objection shall be required to provide training in or to perform induced abortions. Otherwise, access to experience with induced abortion must be part of residency education. This education can be provided outside the institution. Experience with management of complications of abortion must be provided to all residents. If a residency program has a religious, moral, or legal restriction that prohibits the residents from performing abortions within the institution, the program must ensure that the residents receive satisfactory education and experience in managing the complications of abortion. Furthermore, such residency programs (1) must not impede residents in the programs who do not have religious or moral objections from receiving education and experience in performing abortions at another institution and (2) must publicize such policy to all applicants to those residency programs.

Abington Health did not responde to a request for comment on how this training would have been handled if the partnership with Holy Redeemer was implemented. “Most of us came to this program because we were looking for a program that provided these types of services that would be cut off by the merger,” says Cari Brown of Easton, Pa., a second year resident in AMH’s OB/GYN department. “In this particular situation, our treating and our ability to provide these services are potentially being compromised because of a religious belief that I would estimate the majority of our residents do not or have not subscribed to.”

Brown, who along with 19 other residents released a letter on July 11 disapproving of the merger, says she only applied to AMH’s OB/GYN program because of the advanced abortion services it offers. If the merger would have grown feet, instead of being squashed over two weeks after its announcement, then that education, she says, would be severely limited.

But it’s the Victory that Matters

“Can you believe they never spoke to the doctors?” Poley asks with astonishment. “It makes you think, doesn’t it?”

“The fact that they had to do it in secrecy and announce it from the cloak of secrecy says it all,” she continues. “What were they thinking? They had to know they were going to meet up with resistance. They just had no idea of what the extent of it would be.”

And that resistance is thought to have brought the affiliation to a halt.

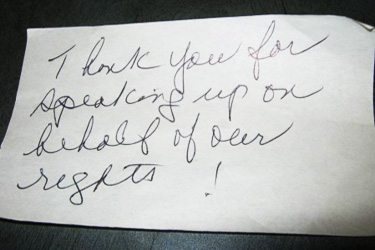

Rita Poley. The Jewish Exponent.

Reynerston says the campaign against the merger possessed two key attributes in successfully bringing it down: opposition by the the surrounding community and by the medical community. “Without community support and without doctor support, proposals tend to fail and that’s exactly what happened,” she says.

When Reynerston heard the news, she just finished a call with Abington advocates and was completing a follow up email when an involved resident sent out a mass email announcing the merger’s termination. “It was really great. It was a great moment,” she says.

For Brown, now that the merger has been called off, she looks forward “to continuing to offer patients the complete range of reproductive health-care options, and supporting them through the joyful, as well as the challenging, moments that they and their families may encounter.”

“I hope our community never needs to face a situation of putting one groups’ religious doctrine ahead of evidence based medicine again.”

Rabbi Sernovitz believes that Abington Health and Holy Redeemer’s July 18 decision “speaks volumes about the power of the people to make change and to pursue social justice.”

And Poley, exhilarated by the news, felt “happy and lucky to be living in this community where these great people came together and caused this to happen.”

But what happened in Montgomery County from July 3 to July 18 is more than about the cessation of a potentially problematic and harmful merger. It’s a striking example of how powerful and effective grassroots organizing can be when assertively tackled.

“This campaign is going to be a great working example for other communities in the future when we no doubt have to face another [merger],” says Reynerston.

“Communities across the nation can now look to Abington, Pennsylvania for proof that it does make a difference when people stand up and speak out about a hospital merger that could have an impact on health care.”