Our Bodies, Ourselves: Turning 40, Going Global

Born in Boston, Our Bodies, Ourselves has become an international force for women's rights.

Cross-posted with permission from the Center for Genetics and Society.

It’s 1969 and East Coast to West, there are marches and teach-ins and sit-ins and rallies. People are taking to the streets, gathering in church basements, walking out of classrooms to protest the war in Vietnam, demand civil rights, and press feminist agendas.

Everywhere, women’s power symbols are popping up: on the Boardwalk at Atlantic City, where a sheep is crowned Miss America while Bert Parks croons to pageant goers inside the Convention Center; at the University of Washington student Hub, where Bernadine Dohrn, National Secretary of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) joins a roster of Seattle peace and justice activists to discuss the “woman question”; in Chicago, where hundreds of women from leftist organizations and causes gather and found the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union.

In Boston on May 4th that year, some 500 women make their way to the Fenway neighborhood for a conference in the red brick halls of Emmanuel College, then, as at its founding by the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, an all-female institution. In 1999, activist and author Susan Brownmiller would write about a performance she saw that day in which members of the radical separatist feminist group,Cell 16, publicly cut off their hair to protest male domination. Nancy Miriam Hawley, whose work with the SDS had led her to help organize the conference, later characterized the milieu and the women who were drawn to Emmanuel to talk about women’s rights: “Many of us were involved in other movements for liberation – the New Left or civil rights or the antiwar movement. When the women’s movement came along, it hit home, because it was addressing our oppression as women, which we hadn’t identified before.”

Hawley, who would go on to work for years as a clinical social worker, group therapist, and organizational consultant, served at the conference as the leader of a workshop. She recalled, “A number of us were particularly concerned about health issues because as young women, were having our first babies, and birth control and childbirth were prominent issues for us.”

Indeed, the conference galvanized the attendees, some of whom soon formed the socialist women’s organization Bread and Roses, which in 1971 opened the Women’s Center in Cambridge, still running today. And many of those who attended Hawley’s workshop kept in touch. They continued to meet to talk about their experiences with doctors and childbirth, pregnancy and sex, finding that all of them had struggled with bad advice or ignorance or ill treatment or indifference at the hands of the medical establishment. In their words, “We discovered there were no ‘good’ doctors and we had to learn for ourselves.”

So they devised a survey and administered it to as many women as they could. They began doing their own research, consulting medical texts and journals. They interviewed willing physicians and nurses. The process was energizing. “We were excited and our excitement was powerful. We wanted to share our excitement and the material we were learning with our sisters. We saw ourselves differently and our lives began to change,” they wrote.

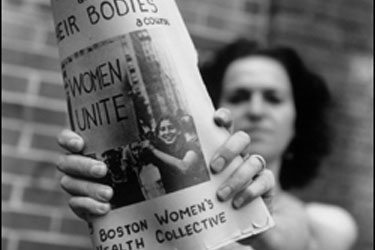

The sharing of the “excitement and the material” took the form of 193 pages of typewritten text, grainy photos, and hand-drawn illustrations reproduced by mimeograph. Roughly lettered on the cover was, “Women and Their Bodies, a course,” and, down at the bottom “75¢”. The introduction closed with “We want all your ideas, comments, suggestions, criticisms, etc. Power to our sisters!!” and was signed, “Nancy Hawley, Wilma Diskin, Jane Pincus, Abby Schwarz, Esther Rome, Betsy Sable, Paula Doress, Jane de Long, Ginger Goldner, Nancy London, Barbara Perkins, Ruth Bell, Wendy Sanford, Pam Berger, Wendy Martz, Lucy Candib, Joan Ditzion, Carol Driscoll, Nancy Mann, and all the other women who took the course and read the papers.” The table of contents, rendered in a neat italic hand, bore the helpful notation: “For a notebook: punch holes in the wide margins and slit the binding thread and back of each booklet with a razor blade.”

Within a year, a version that didn’t require nimble use of holepunches or razor blades came out from the New England Free Press and quickly was adopted as the centerpiece for women’s group discussions around Boston and beyond. More than 250,000 copies were sold, largely by word of mouth. The book became a dogeared staple of co-eds’ shelves, a trusted reference at alternative women’s clinics, and an assurance for pubescent girls too embarrassed or afraid to consult anyone else for information.

That book was, of course, Our Bodies, Ourselves, whose fortieth anniversary will be celebrated this October, when it will be issued in a ninth edition. Published since 1973 by Simon & Schuster, it has sold 4.5 million copies in 26 languages, including Braille, and is arguably the most influential work on women’s health and sexuality in history. By performing the radical inversion of giving female experience and knowledge primacy over that of physicians and medicine with a capital “M”, the women who collaborated on the text helped spawn the consumer health revolution.

Such a trajectory was never anticipated. No one had an inkling that from the first edition would emerge a publishing phenomenon. The whole enterprise began with the simple, and profoundly traditional, impulse the women at the Emmanuel College workshop had to talk about the home truths of their bodily experiences as women and mothers. Out of sharing their stories came an agenda, partly motivated by frustration and a sense of injustice, and a determination to pursue knowledge in the face of a dismissive medical establishment, despite deep intellectual insecurities: “We were just, women,” read a line in the introduction of the first edition, “what authority did we have in matters of medicine and health?”

This uncertainty actually proved a boon, leading to a crowd sourcing approach long before the term was coined. As the introduction of that first mimeographed version proclaimed, “[These papers] are not final. They are not static. They are meant to be used by our sisters to increase our consciousness about ourselves as women, to build our movement, to begin to struggle collectively for adequate healthcare….” Women across the country responded, sending in feedback, identifying gaps—not enough material, some said, on high-dose-estrogen contraceptives, ectopic pregnancy, or lesbianism—and providing material for new editions. Hawley recalled, “At some point in these early printings, we realized that the title Women and Their Bodies was itself a sign of our alienation from our bodies. We changed the title to Our Bodies, Ourselves, because that was what we were really talking about.”

Like the Whole Earth Catalog, Our Bodies Ourselves was effectively a social networking device: It served as both a source of reliable information outside normal institutional channels and a means of connection. The book answered the needs of the burgeoning women’s health movement. Wrote Susan Brownmiller in In Our Time, “Women’s centers in big cities and college towns were thirsting for practical information and new ways to organize. The Boston women’s handbook with its simple directive, ‘you can substitute the experience in your city or state here,’ fit the bill.”

Eventually, the small group that incorporated first as the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, then as Our Bodies Ourselves also had to deal with changing political tides. They faced both public censure and legal attacks. After Our Bodies, Ourselves was picked in 1976 by the American Library Association as a best book for young adults, right-wing groups waged multiple campaigns to get it banned from school libraries.

Meanwhile, the book moved social scientists and physicians toward a new focus on health issues unique to women. Brandeis University sociologist Irving Kenneth Zola, giving a presentation at the 1990 conference of the American Sociological Association in Washington, D.C., said, “Its message was and is about the importance of women’s perspectives in health care, man’s domination in general, and medical domination in particular, the necessary breakdown of the split between public and private worlds, and the role of the body in one’s identity.”

In short, the assumptions underlying Our Bodies, Ourselves inspired women of all stripes to question the reigning authority of the medical establishment and demand answers. The institutional response to women’s questions was profound, leading to a shift in national and international medical research agendas and in funding priorities (think breast cancer). Assertiveness regarding women’s healthcare laid the groundwork for other activists, such as those who sought fastlane approval for HIV/AIDS drugs. It is difficult to imagine the whole consumer health movement having emerged without the efforts forty years ago of that handful of bold women in Boston.

The collective, which now mostly goes by the acronym OBOS, went on to publish other volumes, including Changing Bodies, Changing Lives for teens;Ourselves, Growing Older; and Sacrificing Ourselves for Love. At the same time, women’s groups worldwide began to translate and adapt the text. Kathy Davis’s 2007 study from Duke University Press, The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves, has a three-page appendix listing foreign-language editions, from Denmark to Senegal to Indonesia to Nepal.

That work continues apace. Through its Global Initiative, which recently received substantial support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, OBOS is working with women’s groups in Eastern Europe, South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and Russia to help them reframe and adapt the text to suit their particular educational, cultural, and medical needs, as well as to gain political rights. Judy Norsigian, a founding member who is now executive director of OBOS, told me in a phone interview, “We don’t take any credit for the original development of these cultural adaptation projects. Women in other regions created these projects and then came to us for the technical resources and other help that has enabled many of them to succeed. We’ve been glad to be able to support them.”

For its 40th anniversary conclave in Boston on October 1, OBOS will host a symposium featuring dozens of international visitors. The symposium committee includes the likes of Michael and Kitty Dukakis, Ellen Goodman, Katha Pollitt, Eleanor Smeal, and Gloria Steinem. To mark the anniversary, memories of the book’s impact being gathered by University of Cincinnatti historian Wendy Kline via an online survey.

On Our Bodies, Our Blog, many readers whose lives were changed, in small ways and large, by their encounters with the frank and forthright text, have posted their recollections. Let Meg Sawicki’s April 30, 2011 entry stand as a summation of many women’s experience:

The first time I saw “Our Bodies, Ourselves” was in 1977 and I was a freshman in college. Some women I knew had the book and I remember thinking how fantastic it was that a group of women had written a collection of stories that shared their own wisdom about health and life and being a woman. For the first time I was affirmed that different was okay, and I was hooked….I have only love and admiration for those first brave women of the Boston Women’s Health Collective who gave us real and important information about our health and happiness, and who set the bar for other women’s self discovery books….