Judicial Fact-Finding Isn’t Just Legitimate, It’s Crucial

One complaint that has been lodged by anti-choice activists since the Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt decision is that courts are an improper place for evaluation of science. This concern misunderstands the role of courts and the way that scientific evidence is evaluated.

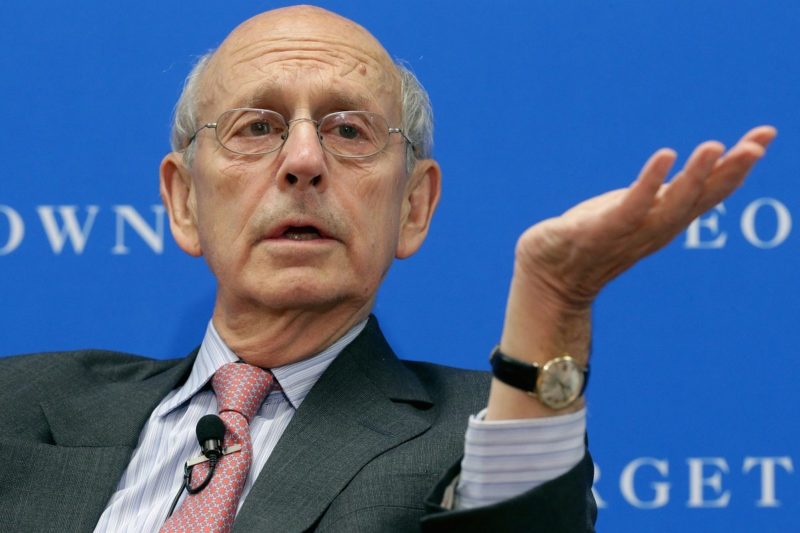

On June 27, the Supreme Court ruled 5 to 3 in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, its biggest abortion-related case in 24 years, in favor of abortion providers in Texas. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Stephen Breyer signaled to legislatures and judges that it is constitutionally unacceptable to rely upon junk science when evaluating restrictions on abortion care.

Justice Breyer has validated what advocates have known for years: Legislative efforts used to justify abortion restrictions do not reflect reasonable disagreement over science.

The restrictions at issue in Whole Woman’s Health included legislative findings claiming that those restrictions were necessary to protect women’s health. Those findings were based on unproven claims, providing yet another piece of evidence that such laws have nothing to do with women’s health but are rather bare attempts to reduce or eliminate access to abortion care. The Supreme Court has now finally stated unequivocally that courts cannot let these sham laws based on false scientific claims stand without judicial scrutiny.

The decision, however, was not without criticism. One complaint that has been lodged by anti-choice activists since the decision is that courts are an improper place for evaluation of science. This concern misunderstands the role of courts and the way that scientific evidence is evaluated in courts, and also fails to recognize how rudimentary the Court’s ruling in Whole Woman’s Health actually is.

A district court is a trial court, and trial courts are designed for fact-finding. Our judicial system is built on an adversarial process in which two opposing parties present evidence to create a factual record. Because courts are not experts on science, scientific evidence is generally presented through expert testimony. Judges serve as the gatekeepers of that testimony and must evaluate the legitimacy of expert testimony before it can be included in the record. The exact standards for admission of expert testimony vary by state, but all courts must follow a basic standard. Courts then base final decisions on the record created at trial.

Trial court decisions can be appealed, reviewed, and overturned if an appellate court thinks the trial court did a poor job managing the development of the factual record, including improper admission of expert testimony without sufficient factual basis. Officers of the court—judges, attorneys, etc.—are therefore charged with engaging in careful and thorough admission and interpretation of evidence to arrive at findings of fact, a standard intended to be enforced on appeal.

Courts generally follow a principal of deference to legislative findings of fact. This general deference is rational, especially where reasonable minds can disagree on the evidence upon which those findings are based. Legislators are elected and therefore (in theory) represent the people they govern. Legislators may call upon a wide range of evidence and shared understandings of the public to arrive at appropriate legislation and therefore (in theory) are able to pass broadly informed legislation for their constituents.

But when the views of the most powerful political voices go against the weight of the evidence, the importance of the judiciary’s role as gatekeeper and evaluator of evidence becomes starkly clear.

Justice Breyer reminds us in Whole Woman’s Health that even in Gonzales v. Carhart, a 2007 decision that is well known for upholding a restriction on abortion, “we must not place dispositive weight on [legislative] findings.” In fact, “the ‘Court retains an independent constitutional duty to review factual findings where constitutional rights are at stake.’” Although the Court ultimately upheld the restriction at issue in Gonzales, the Court noted that where “’evidence presented in the District Courts contradicts’ some of the legislative findings … ‘[u]ncritical deference to [the legislature’s] factual findings … is inappropriate.”

In this scenario judicial fact-finding is not only legitimate, it is crucial.

To be sure, district courts are not suited to be the sole arbiters of scientific evidence. Judges are no more reproductive health professionals than legislatures are, and bad actors exist on the bench just as they do in legislatures. Judges have certainly been guilty of ignoring science and upholding unjustifiable abortion restrictions. But Justice Breyer does not argue that courts be the only or even the primary evaluators of scientific evidence. The Supreme Court’s decision here should be interpreted as a directive to legislatures just as much as it is to courts, signaling to lawmakers that if they pass scientifically unsubstantiated laws that infringe on fundamental rights those laws will strongly risk being overturned.

This is not a controversial new idea. It is merely a requirement that courts and legislatures do their jobs in the ways they were designed to.

Whole Woman’s Health should usher in an era where both types of fact-finders in our system engage honestly with scientific evidence, especially where fundamental rights are implicated. Justice Breyer’s call for basic judicial scrutiny and the acknowledgement that scientific evidence is critically relevant to decisions about human dignity and fundamental constitutional rights come as an enormous relief to reproductive rights, health, and justice advocates who have grown despondent over the way that courts have simply deferred to legislative fact-finding based on unsound or nonexistent evidence.

Going forward, advocates hope courts and legislatures will heed the Supreme Court’s call to ensure that scientific integrity undergirds lawmaking and will thereby strive toward equal access to safe and dignified reproductive health care.