The Issue of Trans Student Rights Inches Closer to the Supreme Court

With several cases in the legal pipeline, it's becoming a question of when—not whether—the Roberts Court will step into the fight over transgender rights and bathroom access.

On August 29, the Gloucester County School Board in Virginia will file a request asking the U.S. Supreme Court to step into the fight over whether transgender student Gavin Grimm can use the bathroom that aligns with his gender identity. Grimm’s case is not the first of its kind, but it has become one of the most high-profile.

At this point, it’s not a question of whether the Roberts Court is likely to take a case concerning what rights transgender students have under Title IX. It’s more a question of when.

Title IX of the Education Amendment Act of 1972 is a federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally funded education program or activity. Historically, civil rights advocates have used Title IX to guarantee female students access to equal classes, facilities, and educational opportunities. It’s also recently become an important, if flawed tool in addressing campus sexual assault.

“Basically anything distinguishing between boys and girls or men and women is prohibited under Title IX, unless there is a specific exception in the statute or regulations allowing it to happen,” Joshua Block, senior staff attorney with the America Civil Liberties Union’s LGBT & HIV Project and one of the lawyers on Grimm’s case, explained to Rewire in an interview.

Title IX has some small carve-outs for when and under what conditions schools may discriminate on the basis of sex, Block noted. “The Department of Education has passed very detailed regulations saying when you do and don’t have to integrate a sports team,” he explained. “It’s passed detailed regulations on under what conditions a school [can] offer sex-segregated classes. Those would otherwise be prohibited unless … authorized by the regulation,” he said.

Among the carve-outs for allowable sex-segregation under Title IX is a regulation dealing with restroom and locker room access, which is at the heart of cases like Grimm’s. And it’s that carve-out that has sparked the legal fight over trans rights at school.

“There is a long-standing regulation that says schools can have separate restrooms and can have locker rooms divided by sex,” said Block. “Now fast forward 40 years later and you have school districts saying that this regulation not only gives them permission to have boys’ and girls’ rooms, but it gives them permission to essentially banish transgender kids from those restrooms by saying they can’t use a restroom consistent with their gender identity.”

The legal landscape of trans student rights to access restrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity has been shifting well before Grimm’s lawsuit. Since as early as 2009, schools in places like Maine and Illinois have faced lawsuits for prohibiting students from accessing restrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity. Meanwhile, states like California and Colorado have provided affirmative protections for transgender students in the form of nondiscrimination laws so students can use restrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity. But that means transgender students across the country are subject to a patchwork of legal protections that are not uniform across the country: A trans student in California has, at least in theory, more legal protections against discrimination at school than one in Mississippi. So for many trans students, Title IX is the only legal protection against discrimination they have.

Through a series of administrative actions, the Department of Education (DOE) since 2013 has tried to nudge reluctant school administrators toward understanding the difference between providing for sex-segregated facilities and using those facilities as justification for discriminating against transgender students. It has notified federally funded schools that failing to allow transgender students access to restrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity will subject those schools to litigation and risk their federal funding. In other words, the DOE made explicit its interpretation of federal law: Schools may have sex-segregated facilities like restrooms, but they cannot determine on the basis of gender identity which students have access to which facilities.

Significantly, the Obama administration filed a friend-of-the-court brief in Grimm’s case, urging the federal appeals court to follow its lead on interpreting Title IX to protect against gender identity discrimination in schools. So far, both the district court and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals have listened to the administration, deferring to the federal agency on how best to interpret the regulations that agency publishes. Those rulings have been temporarily put on hold while the Gloucester School Board files its request to have the Roberts Court step in.

This brings us to the conservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and the lawsuit filed by more than 20 states in May arguing that the Obama administration has overstepped its authority on this matter. It’s similar to the argument raised by Gloucester County in the Grimm case and rejected by the Fourth Circuit.

Raising those arguments in the conservative Fifth Circuit, the same federal appeals court that blocked the Obama administration’s executive action on deportations, is a strategic bet by conservatives that they can get a ruling in their favor. Such a ruling would create a likely circuit split, or disagreement, in the appellate courts—which is exactly the kind of situation the Supreme Court is set up to resolve.

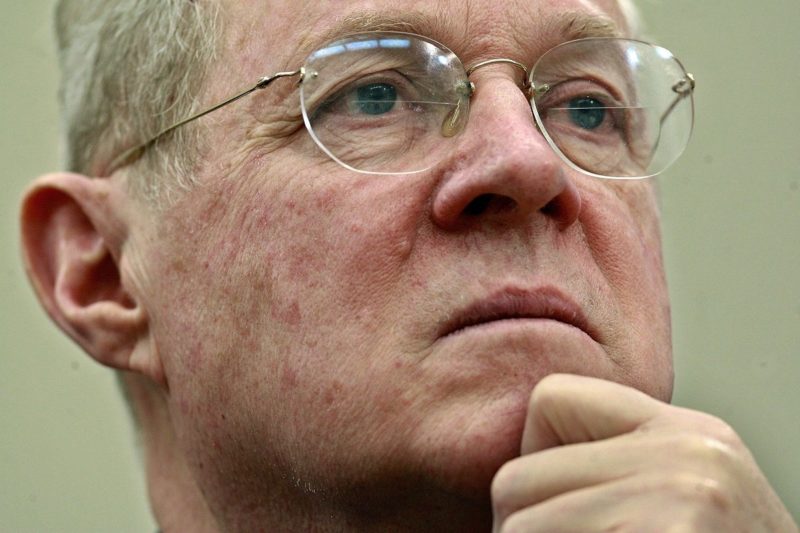

Once again, Justice Anthony Kennedy is poised as the swing vote, the justice each side needs to rule in its favor. And while Kennedy has emerged as a moderate but leading voice in the jurisprudential recognition of LGBTQ rights, he has also been critical of some Obama administration agency action. Cases like Grimm’s, or whichever transgender rights case the Court eventually takes up, will present the ultimate test for Kennedy: Which matters more, his desire to see the “dignity” of the LGBTQ community advance in the law, or his distrust of executive authority—even if that executive authority advances LGBTQ dignity?