Chicago’s ‘Pregnant Men’ Ads: Flipping the Dialogue on Men and Teen Pregnancy Prevention

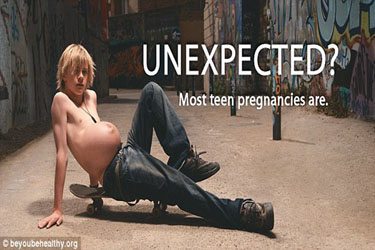

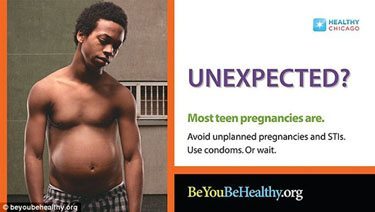

The Chicago Department of Public Health’s Office of Adolescent and School Health just released a new set of teen pregnancy prevention ads that feature images of half-naked young men who appear, thanks to technology, pregnant.

The Office of Adolescent and School Health in the Chicago Department of Public Health (Chicago DPH) recently released a set of teen pregnancy prevention ads that feature images of half-naked young men who, thanks to technology, appear pregnant. When I first saw the ads, I thought, “Wow, how progressive! Chicago is actually creating ads that are trying to be more inclusive of transgender men.” Well, hope springs eternal—and in this situation, mine was completely misplaced. The ads are actually an attempt to get cisgender boys’ and men’s attention in order to charge them with stepping up when they are part of an unplanned pregnancy.

These ads are not the first of their kind. Just a few months ago, the New York City Human Resource Administration put out subway and bus ads, which received well-deserved criticism because of their negative messaging to girls and about boys and young men. With photos of young children accompanied by messages like, “Honestly, Mom—chances are he won’t stay with you. What happens to me?” the New York ads promote stigma, fear, and shame, which, as a strategy, is as unethical as it is ineffective for inspiring behavior change.

Milwaukee had its own teen pregnancy campaign last year. The Milwaukee ads featured the same photos as the ads in Chicago, but the unfortunate tag line was, “It shouldn’t be any less disturbing when it’s a girl.” The charges against these ads are that they are transphobic, labeling a transman who chooses to get pregnant “disturbing,” as well as shaming teen girls who do get pregnant by implying that they, too, are “disturbing.” I agree completely with these criticisms—but for the purposes of this piece, I want to dial it down to a very basic admonishment: If the Milwaukee ads were designed to reach boys and young men, they completely missed the mark.

Dr. William Pollack has done extensive research on adolescent boys and young men, from which emerged what he named the “boy code”—the unwritten set of rules that dictate to boys through unconscious assimilation how they are supposed to behave in order to fulfill the culture’s expectations of what it means to be masculine and, eventually, a “real man.” Although influenced by values, traditions of individual cultures, and other diversity, there are aspects of the boy code that apply to all boys. And while I have always struggled with the idea that the boy code and other research on how people learn “genders” educational interventions, I have to say that after having worked with thousands of adolescent and teen boys over the last 20 years, I have seen firsthand that the boy code exists. And when I have used the suggestions Dr. Pollack and others have given for how we as adults navigate the boy code I have also experienced far more successful interactions and interventions with male-identified students. If we can suspend our resistance for a moment and instead take a look at what the boy code posits to see what we can learn from it, we may actually be able to create messages that resonate with boys and young men instead of shaming, minimizing, and even alienating them.

Of the many lessons from the boy code, perhaps the two most salient in terms of how we can reach guys more effectively with teen pregnancy prevention and sexual health education messages are that a) boys tend to be more concrete than abstract learners, and b) the single most important thing to boys and young men is respect. There is far more to the boy code than that, but I want to hone in on these here. Taking these two alone, by definition neither the New York nor the Milwaukee ads will resonate with their target audiences. In the New York ads, guys are nonexistent. Therefore, the ads reinforce what many young men already believe: that when a girl or woman becomes pregnant, the pregnancy or baby is her responsibility.

The Milwaukee ads, aside from being offensive, are too abstract; what is the connection between identifying something as disturbing and a male partner’s role in teen pregnancy? In addition, regardless of tagline or message, threatening guys does not work. What would work? Appealing to their need for respect and highlighting their strength in being active participants in their sexual relationships and decision-making. For years, the My Strength campaign has been a great role model in this with a campaign that features different photographs of men with their partners (at least one of which is a same-sex couple) and the tag line “Our strength is not for hurting,” along with a different statement on each, such as “So when she wanted to stop, I stopped.” The messages are direct without being accusatory. They are clear. They acknowledge that boys and men have strength, leaving room for a flexible definition of strength, and appeal to this valued strength. The ads neither threaten nor shame guys, and I have heard from countless teen and adult men that both the approach and messages resonate with them.

So now, let’s come back to Chicago. No intervention is perfect, and there are always positives and negatives. Let’s start with the positives:

-

Guys are present. How often do we hear boys and men mentioned, let alone visually represented, in materials relating to sexual and reproductive health? It has been great to see an increase in so-called male involvement programs and organizations working with boys and young men, so we are certainly making some progress here. But the vast majority of sexuality education curricula available to the general public, media stories about sexuality, and other interventions continue to focus first and foremost on girls and women. We need to go beyond treating boys and men as an afterthought in sexual and reproductive health and reinforce for them that they are equal participants in sexual health-related issues with their female partners.

-

The tag line on the Chicago ads does not use fear or shame. Instead, it provides information followed by specific action steps: “Unexpected? Most teen pregnancies are. Avoid unplanned pregnancies and STIs. Use condoms. Or wait.”

The ads, although far better than both Milwaukee’s and New York’s, have their limitations:

-

The tag line could be more direct. The boy code would posit that the tag line should read, “Or wait to have sex.” The fact that the word “sex” isn’t used shows yet again that the adults who say they are interested in working with and supporting young men can’t even talk directly about what they’re talking about. And young people don’t get politics; they don’t know that in our hypocritical culture that is saturated with sexual images and messages everywhere we look, the outcry against a public service message featuring the word “sex” could stop the campaign before it gets off the ground.

-

The ads are unnecessarily sensationalistic. It was imperative for the people implementing the campaign in Chicago to change the tag line—but, ironically, once they did, the intended power of showing pregnant young men dissipated. And the resulting language, which is better because it does not shame, is now watered down. We need to communicate that pregnancy is a huge deal, regardless of whether it’s planned or unplanned. And while I applaud them for not threatening or admonishing the guys, we need to be far more direct about male roles and involvement.

And, to not lose sight of the original concern with the Milwaukee ads, even with the deletion of shaming language, colleagues in Chicago have underscored that the image of a pregnant man remains offensive to some transmen and their allies. The Chicago DPH did vet the images with professionals working specifically on transgender issues, who said they did not find the ads offensive. Perception is, of course, subjective.

I don’t envy these individuals at the Chicago DPH. They are trying. Many of us have tried media campaigns or messages—or written articles or blogs—that are well-intentioned but that are then fiercely criticized. We know from media experts that when we are trying to reach the general public, images and messages need to be provocative and even sensationalistic sometimes in order to get, and keep, people’s attention. Videos that go viral and messages that are retweeted are the ones that get us thinking, feeling, and talking—whether the messages are positive and uplifting or button-pushing. The Chicago ads certainly promise to do that. But I think we can all agree that ads alone are not enough to change behaviors, so organizations in Chicago, and all over the United States, need to be thinking about and planning what they can do now that these messages are out there. If the ads do get guys’ attention, what then? If they come into your clinic for an appointment, are your services male-friendly? If they attend your educational workshops, are the lessons not simply inclusive of but specifically geared toward learners of all genders? As a character says in the movie Field of Dreams, “If you build it, they will come.” We need to reach out to more young men, but when we do, we need to be ready to work with them in ways that specifically resonate with them. Only then will we truly inspire their involvement, rather than punitively requiring it.